Committee to Save World Is a No-Show, Pushing Economy to Brink

They may have waited too long and until now done too little, and it’s unclear who is going to save them.

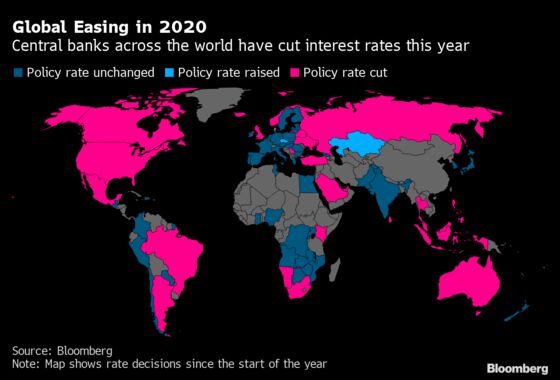

(Bloomberg) -- From Washington to Berlin, London and Tokyo, governments and central banks are rolling out measures meant to soothe markets and cushion their economies from what increasingly looks like the first global recession since the financial crisis just over a decade ago.

Their problem: They may have waited too long and until now done too little, and it’s unclear who is going to save them.

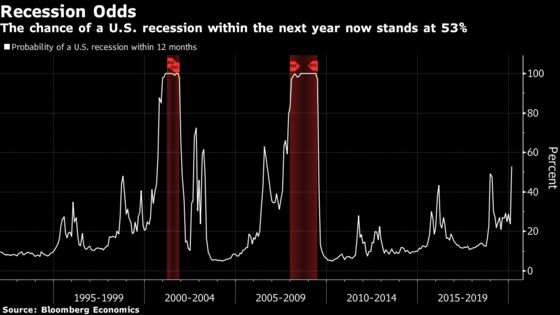

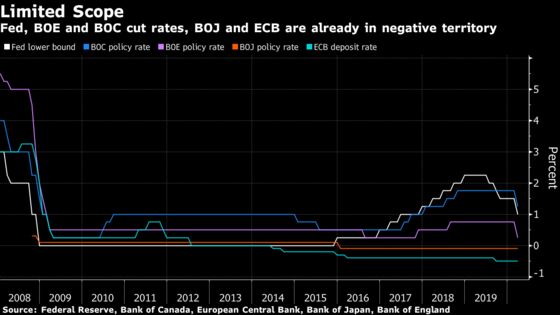

As officials scramble to limit the mounting economic damage of the coronavirus still infecting thousands worldwide every day, financial markets tumbling in ways not seen in decades have put the spotlight on central banks’ low ammunition and politicians focused on their domestic politics rather than a global response.

The lessons are being learned in real-time. France’s Emmanuel Macron said Friday that G-7 leaders would hold a conference call Monday to discuss the crisis and Canada’s Justin Trudeau said the leaders had agreed to coordinate their response.

The move toward something like the April 2009 G-20 summit in London that helped galvanize the world in its response to the economic crisis then encouraged investors on Friday. It is coming, though, after weeks of global cooperation failing to gain traction that have laid bare the discomfiting reality that vital institutions and diplomatic bonds built over decades have been weakened by what those involved complain has been a leadership vacuum.

“I don’t see that ‘Committee to Save The World’ emerging yet,” said former senior official at the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury Nathan Sheets, who’s now chief economist at PGIM Fixed Income. He was referring to the Time magazine cover from 1999 featuring then Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan and Deputy Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers.

The picture coming out of more than a dozen Bloomberg News interviews with policy makers around the world and people close to them is of leaders and technocrats who were initially too sanguine about the potential spread of the virus and its economic fallout. They were divided over the need for action and then struggled to catch up and join forces.

The urgent questions now are whether authorities can overcome mistrust between governments -- and even within them -- and whether the actions now finally being taken will help avoid a downturn that, even if it is short-lived, could carry profound political and economic consequences.

Word of the G-7 leaders call came via a Twitter post from Macron, who said the goal was to “coordinate research efforts on a vaccine and treatments, and work on an economic and financial response.”

It’s not clear, however, what will merge from that call. So far, the struggle for rapid collective action “just conveys how fragmented and behind we are” in managing a common crisis and how institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and Group of Seven are in a far weaker position than they were in 2008 when they drafted unified policy pronouncements and pledges that amounted to a coordinated response, said Adam Posen, who heads the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington and was a crisis-era U.K. policy maker.

“It would be lovely if we had binding statements on ‘no currency intervention,’ ‘no more tariffs,’ rolling over loans, common commitment on describing the problem and some acknowledgment of the ability to learn from each other,” Posen said. “That’s not in the offing right now.”

Much of the concern in markets has focused on President Donald Trump’s administration, which after weeks of playing down the threat of the virus and its economic cost, began this week to lay out at least its plans for stimulus if not actually announce them.

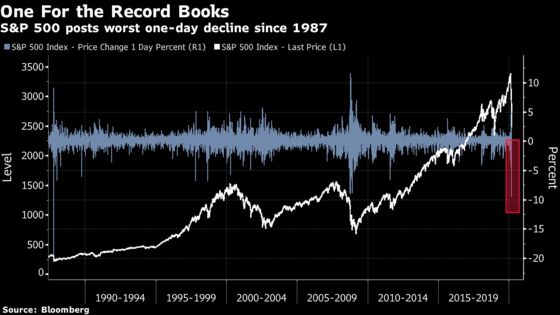

After Trump addressed the nation Wednesday and announced new strictures on trans-Atlantic travel, markets crashed worldwide Thursday. The S&P 500 Index fell the most since 1987.

But stocks rebounded Friday after Germany abandoned years of steadfast fiscal hawkishness and said it would spend aggressively to combat the crisis and without limits, even raising the idea of taking on additional debt to finance the spending spree.

The Trump administration has been caught in its own internal fights over what to do even as it has battled with Republicans and Democrats in Congress over options like a payroll tax cut that could cost a trillion dollars or more. There were signs of progress on Friday in negotiations with Democrats. But the criticism of inaction and mixed messages has not been limited to the U.S.

Before Friday’s abrupt turnaround in Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government initially proved reluctant to abandon its long-standing balanced-budget policy despite its economy already stalling out. While Merkel now says governments should do “whatever is necessary,” and people familiar with the matter say she is willing to accept deficit spending, it’s not clear how effective the plan announced Friday will be.

In a potential model of coordination that still failed to fully placate investors, the Bank of England on Tuesday cut interest rates and introduced lending programs hours before the British government unveiled a spending spree.

In Japan, officials had hoped that a sputtering economy could ride out the impact of the virus after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe unveiled a 13.2 trillion yen ($125 billion) stimulus package in December. But when they unveiled additional measures this week, investors were disappointed.

Finance Minister Taro Aso has also been pushing for a coordinated global response to what is becoming a shared crisis.

“What we can do with monetary measures is getting very limited, so we should take fiscal action,” Aso told parliament on Monday. “The global economy will be affected if nations don’t keep action coordinated.”

On a conference call last Sunday to mark the regular bimonthly meeting of the Bank for International Settlements, the Basel, Switzerland-based organization for central banks, some policy makers complained that in many ways they were flying blind.

The inevitable lag in economic data meant there was little hard information they could seize on to guide policy, some on the call complained. They also all weren’t on the same page in their diagnosis of the severity of the economic problem.

Yi Gang, governor of the People’s Bank of China, offered the hopeful message that a turnaround was underway in China, according to people familiar with his presentation.

Ignazio Visco, governor of the Bank of Italy, offered a far direr picture, predicting a 2% first-quarter contraction in the Italian economy alone.

Fiscal Firehose

It’s not just the central bankers who’ve been out of sync.

After privately urging European governments to take more urgent fiscal action, Christine Lagarde, the European Central Bank president, took her concerns public on Thursday as she announced a new package of monetary measures and added that the real need lay elsewhere.

What worried her, she told reporters, was “the complacency and the slow-motion process that would be demonstrated by the fiscal authorities of the euro area in particular.”

“I don’t think that anybody should expect any central bank to be the line of first response. It’s fiscal first and foremost,” she added.

France’s Macron pushed back later on Thursday, saying he doubted whether the ECB’s own prescriptions of buying more bonds and enhancing lending were sufficient. “Will they be enough? I don’t think so,” he said in rare criticism of central bank policy.

Lagarde was among a small group of policy makers including Mark Carney, the outgoing Bank of England governor and Bruno Le Maire, the French finance minister, pushing the same line on March 3 when G-7 finance ministers dialed in for a teleconference, according to people on the call and briefed about it.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell and colleagues had already decided on the need for action the night before and would follow the G-7’s statement with the first emergency interest-rate cut since the 2008 crisis.

But fiscal authorities were still wavering.

In an interview with Bloomberg the same day, Larry Kudlow, Trump’s top economic adviser, dismissed the need for fiscal action and insisted the U.S. economy was “sound.”

He also laid out a vision for a G-7 leaders summit in June that would focus on the wonders of the Trump economic model of tax cuts and deregulation rather than responding to a new global pandemic.

“The whole thing is going to be about growth,” Kudlow said. “We are going to be having a discussion about why these great western democracies, what we used to call the western alliance, that are market-oriented are not delivering the goods.”

France’s Le Maire had been in Berlin the day before the March 3 call pressing the case for fiscal action by Germany and on the line he and Carney called for “massive action” in what appeared to be a clear push for a coordinated response.

But Olaf Scholz, the German finance minister, demurred during the G-7 teleconference, stressing the need to wait and see and be calm.

When it was his turn to speak, Powell spoke about the need for decisive action but did not make any reference to what his central bank would be announcing shortly, according to people who were listening in.

The call, which was moderated by Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, was choreographed. The text of the statement had largely been worked out by deputies during a previously scheduled in meeting the day before.

But no specific measures were discussed, just the general line that they stood ready to take action if needed, people familiar with the discussions said.

The disappointed market reaction that would follow the G-7’s statement and the Fed’s rate cut would start the next leg of a downturn in equities and bond yields, and would signal what has become a common theme since then: the need for bigger and bolder -- and coordinated -- action to save economies from a rapidly spreading outbreak.

| For more on the global response |

|---|

|

One major problem is that the U.S. is not playing the lead role that it has in fighting previous crises. That hasn’t been helped by some of Trump’s moves, such as his complaint on Wednesday about a “foreign virus” or his announcement of heavy restrictions on transatlantic travel without consulting the European Union.

“The coronavirus is a global crisis, not limited to any continent and it requires cooperation rather than unilateral action,” the EU’s top leaders responded Thursday.

Hanging over it all is the legacy of Trump’s trade battles of the past three years and the way they have frayed even historical alliances.

“There is no longer any coordination between Europe and the U.S. when it’s a question of strategic decision making. And it’s regrettable for everyone,” Le Maire said Friday in a television interview. “Europe must defend itself alone, protect itself alone, and be able to confront things alone, to come together as a sovereign bloc to defend its economic interests because nobody -- including the U.S. evidently -- will help us.”

It’s also not clear that the U.S. is ready to take the lead.

“This is one of the concerns that sort of sits in an overarching way over the whole system right now: Where is the leadership? Where is the U.S. leadership, which was one of the defining features of the crisis in 2008?” Philipp Hildebrand, the former governor of the Swiss National Bank and now vice chairman at BlackRock, told Bloomberg Television this week.

Lessons of Isolationism

To some, there are already other ominous historical parallels.

Benn Steil, the author of histories of Bretton Woods and the Marshall Plan, argues today’s situation is not unlike that in 1918 when the Spanish flu epidemic infected a third of the world’s population and left at least 50 million dead. Then, as now, Steil says, the response was hindered by weak leadership from a U.S. that had become more isolationist following World War I.

In the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘40s “that isolation would come, at the end, at a cost to Americans,” Steil says. “And that’s already eminently clear again with the spread of coronavirus.”

The denials and vulnerabilities that have colored the economic response have been shared beyond the U.S., of course.

When the IMF announced Jan. 20 that it was downgrading its forecast for global growth this year by a modest 0.1 percentage point, to 3.3%, it came as Chinese authorities were wrestling with a growing outbreak in Wuhan, the industrial city they would lock down just days later.

Not known outside the fund at the time was the fact that Kristalina Georgieva, the Bulgarian economist who took over as the IMF’s managing director from Lagarde last year, was about to force out the institution’s most battle-hardened crisis fighter.

First Deputy Managing Director David Lipton, a veteran of senior posts in the U.S. Treasury and past White Houses who played a crucial role in coordinating the IMF’s response to crises in places such as the euro area and Ukraine, was appointed to a second five-year term in 2016 and was not due to leave his post until next year.

He was keen to stay. But in a Feb. 7 announcement the IMF said Georgieva had decided Lipton would be leaving within weeks.

‘Serious Blow’

With Lipton’s departure, some IMF veterans saw the loss of a respected backroom coordinator whose experience in the art of multilateral suasion might be just what’s needed as another crisis brewed. His exit “is a serious blow to the institution,” Olivier Blanchard, the IMF’s former chief economist, tweeted the day after the announcement.

A week after the announcement of Lipton’s departure, Georgieva told the Munich Security Conference that coordinated action could be needed within weeks. But the IMF’s calls went largely unheeded.

They also were muddied by what remained its positive forecasts for the global economy, forecasts that haveaged badly. In a Feb. 19 “surveillance note” prepared for a meeting of G-20 finance ministers and central bankers the following weekend, the IMF’s economists reaffirmed its prediction for 3.3% growth.

Buried on page 11 of the 15-page document was a lone paragraph that began: “Global collaboration is essential to the containment of the coronavirus and its costs.”

When the actual ministers and central bankers, including the U.S.’s Mnuchin and Powell, gathered in Riyadh on Saturday, Feb. 22, the prevailing mood was positive.

Behind closed doors both Mnuchin and Powell remained upbeat, with the Fed chief citing private-sector economists who were then forecasting a rebound in Chinese activity by midyear, which would result in only a modest impact on the U.S. economy. Powell also, however, warned of the potential for the virus to spread and that the economic consequences of that were unknown.

Georgieva privately urged the G-20 ministers to take action, says Gerry Rice, the IMF’s top spokesman. She also issued an unusual public statement in Riyadh that, though it repeated the rosy baseline scenario predicted in January and was couched in the fund’s usual sober language, warned of “more dire scenarios where the spread of the virus continues for longer and more globally, and the growth consequences are more protracted.”

Within weeks the IMF would be announcing $50 billion in rapid financing for affected developing countries and Georgieva would be convening of an emergency session of the IMFC, the fund’s governing body.

Some European policy makers in Riyadh were already warning that things could get ugly and found the positive tone in the air frustrating.

“The world economy is facing a clear slowdown and this slowdown might be reinforced by the so-called coronavirus,” Le Maire told reporters. “This is the key question today at the core of discussions within the G-20,” he added. “We have to assess whether there is a necessity to take some economic decisions.”

In private some were even more pessimistic, warning that the prevailing belief that a V-shaped recovery in China was at hand was “naïve” and that policy makers elsewhere were ignoring the reality that inventories were being depleted outside China and that the real impact on supply chains was just weeks away.

Early that Sunday morning, as finance ministers and central bank governors the G-7 met quietly in Riyadh, the crisis was turning in other ways. By the end of the day, a surge of cases in Italy from five to 150 would lead to schools being closed and whole towns in the region of Lombardy locked down.

Catching up with one of his G-20 peers a few days after the Riyadh meeting that took place without any senior Chinese representatives, the PBOC’s Yi would stress that China was returning to work and that the impact on growth would end up being relatively small -- a message that President Xi Jinping had ordered Chinese officials to send.

Some in Europe took that message to mean they might get through the crisis with even less damage. In part, because some of the measures taken in China to cordon off entire cities seemed political unfeasible in a democratic Europe.

Within two weeks Italy would have banned all travel and ordered the shutting down of all stores except for groceries and pharmacies.

The cases and economic damage would also continue spreading in financial markets and both Europe and the U.S., prompting Trump’s televised address and his introduction of new travel restrictions.

“They have some hot spots,” he told reporters on Thursday as he met with Leo Varadkar, Ireland’s prime minister, during his annual St. Patrick’s Day pilgrimage to the White House.

“It’s a virus that’s gone pandemic; it’s all over the world,” Varadkar said in response, as Trump looked on. “Knows no borders. Knows no nationalities. And I think we all need to work together in the world on this.”

--With assistance from Craig Torres, Eric Martin, Yinan Zhao, Steven Yang, Emi Urabe, Yuko Takeo and Zoe Schneeweiss.

To contact the reporters on this story: Shawn Donnan in Washington at sdonnan@bloomberg.net;Jana Randow in Frankfurt at jrandow@bloomberg.net;William Horobin in Paris at whorobin@bloomberg.net;Alessandro Speciale in Rome at aspeciale@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Margaret Collins

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.