Millions in U.K. Covid Loans Went to Inactive or Brand-New Firms

Millions in U.K. Covid Loans Went to Inactive or Brand-New Firms

(Bloomberg) -- As coronavirus ripped through Britain and businesses faced a potentially fatal cash squeeze, a company controlled by one of the U.K.’s richest financiers, John Beckwith, received a taxpayer-backed relief loan for about 3.7 million pounds ($5 million) — even though the firm hasn’t been trading for years.

A Bloomberg News review of almost half of the loans granted under the U.K. government’s 26.4 billion-pound Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) shows that lenders handed out more than 130 million pounds to companies with similarly questionable claims, despite a requirement that borrowers had to be negatively affected by the pandemic.

One emergency loan, for 4.7 million pounds, went to a firm founded just two days before it received the funds, corporate records show. And a 1 million-pound loan went to a company that was dormant before the pandemic’s onset and then went into voluntary liquidation less than a year later.

While such cases made up a relatively small portion of the loans, they raise fresh questions about the government’s attempts to keep details of the loans secret and the extent to which lenders carried out due diligence. The British Business Bank, or BBB, which administered the program, last year declined a freedom of information request by Bloomberg News, citing the need to protect companies’ commercial interests. But before leaving the European Union, Britain was required to share borrowers’ identities under the bloc’s state-aid rules with the EU, which is making the data available. U.K. lenders say repayment rates so far have been higher than expected. Nonetheless, revealing borrowers can help shed light on the effectiveness of the CBILS program.

“There’s a public interest here,” said Michael Levi, professor of criminology at Cardiff University and author of a study on fraud and pandemics. “The ability to check the borrowings and who is behind them makes it easier to get to the funds in good time.”

Under CBILS, banks loaned up to 5 million pounds to eligible small businesses, at interest rates set by lenders. The government guaranteed 80% of the facilities.

None of the borrowers has been accused of wrongdoing in connection with their obtaining the loans, and individual lenders are not named in the EU loan records. The BBB said the monitoring of its Covid-19 aid programs is ongoing and lenders should not claim guarantees if they granted funds which did not meet the rules.

The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy, which oversees the BBB and was ultimately responsible for the emergency loans, is “continuing to crackdown on Covid-19 fraud and will not tolerate those that seek to defraud the British taxpayer,” a spokesman said. “We are working closely with lenders and enforcement authorities to detect and investigate fraud.”

Among the borrowers disclosed in EU records, Bloomberg found about 60 dormant companies — firms that had reported no activity for accounting purposes when they borrowed the funds — including a business controlled by Beckwith, 74.

Tempus Court Developments Ltd. — which Beckwith controls through the holdings of two other businesses — borrowed about 3.7 million pounds in November 2020, the EU records show. Yet the firm did not trade in the year through July 31 and lists assets of 60 pounds, filings at Companies House, Britain’s business register, show. It has filed accounts as a dormant business since 2018.

Beckwith, a Conservative Party donor, referred requests for comment to his son Piers Beckwith, who by e-mail said the loan was used to refinance borrowings secured against properties that are owned by the parent of Tempus Court, Mortar Tempus Court LLP, which isn’t dormant. Piers Beckwith also said the company has about 900,000 pounds outstanding on the taxpayer-backed loan it took from Triple Point LLP.

A spokesman for Triple Point said the lender ensured the client was eligible for CBILS, “and this was further certified by the directors of the borrower.” The loan was also subject to a BBB audit, Triple Point said, without elaborating. A spokesman for the BBB said he could not comment on specific cases, adding that lending decisions were delegated to the banks, which considered companies or the group’s ability to repay the loan.

“These companies, which according to their accounts have no turnover or assets, suddenly springing into action to claim business support should have raised red flags for lenders,” said Ben Cowdock, who leads Transparency International’s U.K. research and reviewed the unaudited Tempus Court business filings.

The criteria companies had to meet to qualify for CBILS left little to interpretation. Firms negatively impacted by the pandemic, with annual revenue of as much as 45 million pounds, were entitled to apply for loans.

Crucially, companies also needed to show they had generated more than half of their income from the sale of goods or services before coronavirus lockdowns drew activity to a halt. Businesses had to self-certify they were impacted by the economic crisis to access the loans and they had to present a “borrowing proposal which the lender would consider viable, were it not for the current pandemic,” according to the BBB.

Yet more than 85 companies had only been around for weeks, or at most a few months, before receiving loans under CBILS, the Bloomberg study shows. One of them is Blue Ocean Topco Holding Ltd. Founded by a former investment banker, Gregory Pezzella, Blue Ocean Topco was incorporated on Aug. 12, 2020, Companies House records show, long after the pandemic struck.

Within just 48 hours, the firm, run by the ex-banker who had earlier worked for Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. in London, obtained 4.7 million pounds in taxpayer-guaranteed loans.

According to public records, Pezzella’s firm has since bought care homes in the northwest of England. Another firm that Pezzella owns, Blue Ocean Midco Ltd., separately borrowed 3.2 million pounds through CBILS in September 2020. Blue Ocean Midco, whose last financial accounts don’t include details on trading activity, is now in administration, filings on the business register show.

Pezzella, who’s listed as a director of 15 companies and has at least two personal profiles in the business register, declined to comment for this story.

“If the scheme was set up to keep existing companies afloat, should banks have granted loans to companies that were incorporated after the introduction of the schemes?” said Frances Murray, senior associate and expert in financial crime at law firm Rosenblatt in London. “In hindsight, banks may have been more vigilant. It was an emergency program, and people have sought the opportunity to abuse the schemes.”

Britain isn’t the only country whose fast-track aid programs struggled to reach the intended recipients as governments tried to strike the balance of moving quickly to avoid economic disaster while putting in enough safeguards to stop taxpayer funds from going to waste. In the U.S., emergency aid was undermined by pervasive fraud, and the programs were criticized for leaving behind businesses owned by minorities.

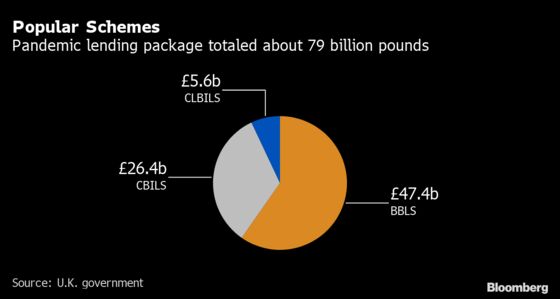

In the U.K., CBILS was one of a number of pandemic lending packages that totaled about 79.3 billion pounds. So-called Bounce Back Loans, which extended 47.4 billion pounds to smaller businesses, have also come under scrutiny for potential misuse, as has a program for bigger companies, known as the Coronavirus Large Business Interruption Loan Scheme, or CLBILS.

One CLBILS lender, the supply-chain finance firm Greensill Capital, has since imploded and loaned millions of pounds to companies that may never repay them. In a report this month, the House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts said that by prioritizing speed the BBB “created additional risks for the taxpayer” as lenders were quickly accredited.

Under CBILS and CLBILS, banks were responsible for conducting credit checks to protect taxpayers’ money and they will need to show they have taken reasonable steps to recover the debt before they can claim state guarantees.

One CBILS borrower, Calibrate Legal Services LLP, illustrates the potential difficulties of recovery. John White, a former managing director at hedge fund GLG Partners and former Morgan Stanley stock trading chief, founded Calibrate in 2018. In June 2020, the company filed accounts to the business register showing that it was dormant through the end of 2019. Yet in August 2020 the company borrowed about 1 million pounds through CBILS.

Less than a year passed before Calibrate went into voluntary liquidation. It has just 151,237 pounds left for creditors including HSBC Holdings Plc, according a report by the firm’s liquidator. HSBC is the only lender listed among the creditors.

White, reached by e-mail, declined to comment.

HSBC declined to comment on whether it loaned the funds to Calibrate but a spokeswoman said the bank “supported British businesses and stayed open to new customers when it mattered most, adhering to the spirit of the schemes because we know how vital U.K. businesses are to keeping our economy healthy.”

HSBC also turned up in a liquidation filing by My Companiie Ltd., founded by Adam Phillips, who appeared on the BBC reality show Dragons’ Den in 2010 to try to raise money for a business making buggies.

My Companiie, which received a 2 million-pound CBILS loan at the peak of the pandemic, had never reported any trading activity to the business register, records show. The firm entered voluntary liquidation this year, owing HSBC a total of 3.5 million pounds; it has just 20,000 pounds of assets available for creditors, filings show. Phillips, reached by e-mail, declined to comment, as did HSBC.

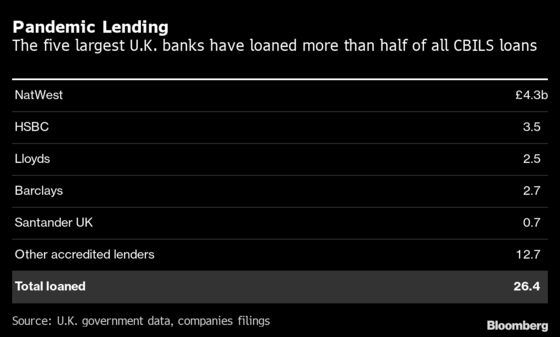

In all, HSBC handed out 3.5 billion pounds of CBILS loans, or 13% of the total, making it the second-biggest lender among the top U.K. banks after NatWest Group Plc.

“None of these companies appear to meet the eligibility criteria” for CBILS, Levi, the Cardiff University professor, said of the Bloomberg study. “If a company is dormant or didn’t exist beforehand then the business would not have been interrupted by the pandemic.” Levi joined the Fraud Advisory Panel and Transparency International last year in calling on the government to name the recipients to accelerate loan recovery.

In assessing the taxpayer-backed lending programs, the National Audit Office said state guarantees reduced lenders’ incentives to conduct their own thorough analyses. In checking their applicants, banks cannot rely on information filed to Companies House because the business register doesn’t have the authority to check filings, a weakness that the U.K. government has pledged to fix.

“The banks acting on behalf of the government needed to engage in due diligence,” said Prem Sikka, emeritus professor of accounting at the University of Essex and a lawmaker in the U.K. parliament’s upper chamber. “There is a big question mark about the whole process and the government needs to be held to account, and therefore, the information needs to be publicly available.”

The Department for Business, which carries the loan risk on its balance sheet, is due to provide details on CBILS in its annual report for the financial year through March 2021. The report is due to be published on Thursday.

The big U.K. lenders say they are seeing good rates of recovery on the loans so far. Alison Rose, NatWest chief executive officer, told Bloomberg Television in October that defaults so far have been better than expected, with 92% of CBILS borrowers paying on time.

Lloyds Banking Group Plc Chief Financial Officer William Chalmers also struck an optimistic note last month. “A very small proportion of CBILS have gone into early stage of arrears,” said Chalmers. “The performance has been comfortably better than our expectations.” Lloyds granted about 2.5 billion pounds in CBILS.

But it is too early to say how many of the loans may sour overall as borrowers have up to six years to repay them. Government and parliament are intensifying efforts to recover funds that are coming due in the meantime.

Lawmakers are promoting a bill to give investigators powers to pursue directors of dissolved companies that took Covid loans. Meanwhile, the government has hired a British startup, Quantexa, which uses artificial intelligence to detect Covid loan fraud, the Times of London reported, citing the Cabinet office. But in some cases it may already be too late.

“The government lacks the legal framework to be effective,” said Sikka. “If the directors are abroad, how are you going to enforce the British law? You can’t.”

Detailed loan records for the U.K.'s Coronavirus Business Interruption Loan Scheme (CBILS) were obtained via the European Commission's data portal (https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/competition/transparency/public?lang=en) on Nov. 6.That data is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. For further details visit:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/#An earlier version of the dataset was obtained from the Copenhagen Business School.The data was combined with corporate account information from the U.K. Companies House database, last updated on Nov. 1. (https://www.gov.uk/guidance/companies-house-data-products)Bloomberg News labeled companies “dormant” if they're designated as such in either the account category or industry classification within the Companies House database. The CBILS program first became available on March 23, 2020, and Bloomberg News identified loan-receiving companies that were created after the date.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.