(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If investors find Nasdaq’s 10 percent slump in October hard to stomach, they’re not cut out for emerging markets.

By conventional wisdom, a stock market enters a correction after falling 10 percent, and bear territory after sliding 20 percent.

Technically, that definition holds for any market – emerging or otherwise. In reality, the declines in the developing world have been much more extreme.

Since 1988, when the MSCI Emerging Markets Index was born, we have seen 14 bear markets with an average decline of about 35 percent over a 28-week period. A similar picture holds for the MSCI Asia ex-Japan Index.

If history is any guide, we haven’t bottomed yet: The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is only 26 percent off its January high.

There have been some recent pockets of enthusiasm – Brazil, for example, just elected a right-wing, pro-market candidate as its new president. The MSCI Brazil Index has gained 14 percent so far this month.

But the biggest elephant in the room is still China, which alone holds more than a quarter of the emerging-market benchmark index's weight. If its stocks tank, the entire asset class is doomed. And there’s good reason to believe Beijing hasn’t managed to find a floor for one of the world’s worst market routs this year.

By my observations, pledged shares, a method China’s private enterprises routinely use to get loans from banks and brokerages, are no longer the focal point. The newest development? Good stocks have gone bad.

Take a look at the benchmark CSI 300 Index. Since Oct. 22 – a recent high point thanks to Beijing’s kitchen-sink strategy – blue chip consumer staples and health-care names have tumbled the most. These are the fallen angels.

To be sure, some of the sell-off is because of earnings. Kweichow Moutai Co. led the baijiu sector’s decline on Tuesday, after it reported almost no revenue or earnings growth in the third quarter.

But the narrative has taken a turn as Beijing tries to milk big companies for cash. After all, the Ministry of Finance’s balance sheet is an open book: China’s fiscal coffers are very short on money.

That’s why Chinese investors are increasingly worried that the taxman is coming for baijiu makers – or that Beijing will play hardball on pricing with pharmaceutical companies selling drugs to the social health-care system.

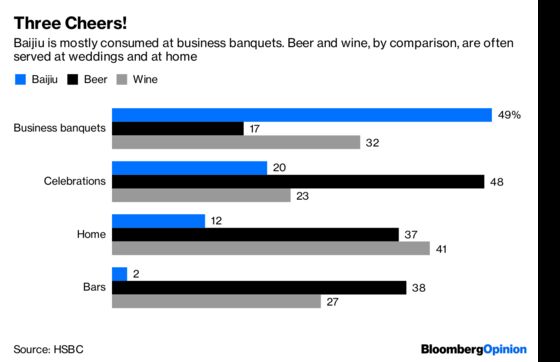

Increasingly, high-end baijiu is seen as a barometer for the health of China’s businesses. Sales of the fiery liquor are no longer an indicator of corruption: Consumption by the government fell to 5 percent of industry sales last year from 42 percent in 2012, according to HSBC Holdings Plc. Now, business banquets account for almost half of baijiu purchases, followed by weddings.

Meanwhile, jammed between a trade war abroad and a liquidity squeeze at home, China’s industrial profit growth tumbled to 4.1 percent in September, the lowest since 2016. Businesses are hardly in the mood to serve 2,000-yuan ($287) bottles.

In bad times, we like to say that cash is king. That may well be the case, now that the U.S. dollar is giving real yield in the money market. But in China, even cash cows aren't sacred. This round of the sell-off isn't over yet.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.