China’s Oil Benchmark Fails Its First Big Test

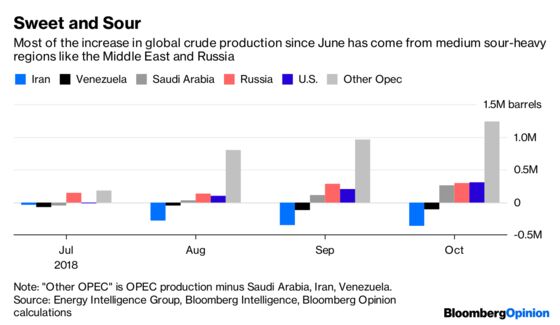

Of the extra 2.09 million barrels a day the world pumped in October relative to June, just 300,000 barrels came from the U.S..

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Since China established its own oil benchmark in March, the world has been looking for a natural experiment to prove whether it could join the West Texas Intermediate and Brent contracts as a price-setting instrument for global markets.

The 29 percent slump in the past two months has provided just that opportunity – and the results don’t look good.

A simplistic way of looking at what’s happened since early October is to consider it a gyration in the wider oil market. Saudi Arabia, Russia and the U.S. have been pumping extra barrels to make up for expected shortfalls as Iran came under U.S. sanctions and Venezuela’s production collapsed. An unexpectedly generous set of waivers for importers of Iranian crude issued by Washington upset that calculation and left the market oversupplied, just as demand for gasoline was starting to look shaky.

A more accurate way to think about it, though, is as a gyration in the market for medium sour crude oil – the sulfurous, viscous variety that’s mainly produced in Russia and the Middle East.

Of the extra 2.09 million barrels a day the world pumped in October relative to June, just 300,000 barrels came from the U.S., where production from the sweet, light fields of the Texas oil patch had already spurted earlier in the year. Some 557,000 incremental barrels came from Russia and Saudi Arabia, and the biggest slice – 770,000 barrels – came from the non-Saudi Arabian balance of OPEC’s membership.

A key selling point of Shanghai’s new crude contract is that it will be tracking medium sour crude at a time when that’s what Asian refineries are increasingly buying. But if sweet light and medium sour were truly turning into separate markets, the price action of the past few months doesn’t make a lot of sense.

For instance, in the early months of this year we’d have expected to see the Shanghai contract trading at a rising premium to WTI and Brent, thanks to the brake on OPEC-Russia’s medium sour supply and excess production of sweet light from the U.S. Then in the past few months we’d have seen a collapse toward parity as OPEC and Russia opened their spigots and Washington took the sanctions pressure off Iranian exports.

Almost the opposite happened. For most of the past year Brent has been priced at a premium to Shanghai crude. While it’s flipped to a discount over the past two months, that appears to be a result of the fact that it peaked and started declining a week earlier, and the Chinese contract has been playing catch-up.

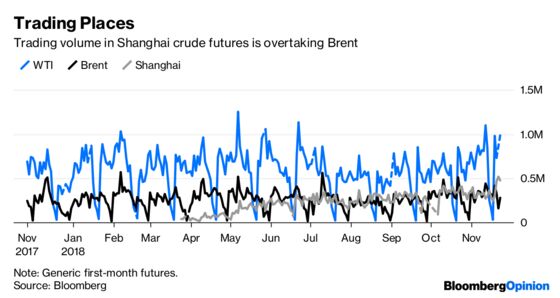

It shouldn’t be surprising that the oil market is still being steered by the same stars. While trading volumes in Shanghai crude have been impressive and even look to be overtaking those of Brent, that’s pretty much the norm in a country whose thirst for commodity trading has seen the equivalent of half the world’s apple crop change hands in a single day.

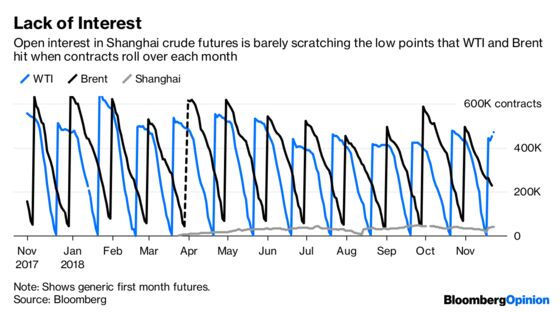

Look at open interest – the number of contracts outstanding – and a different picture emerges. For all the frenzied trading activity, at any one time there aren’t many traders out there making long-term bets about prices using Shanghai’s new crude contracts. Until that changes, China’s oil market will remain a sideshow.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.