(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Eighteen banks coordinating to calibrate a market-driven rate – cynics could be forgiven for thinking that another Libor-rigging scandal is around the corner in China. Perversely, such an outcome would be a good sign for its financial system.

Over the weekend, the People’s Bank of China made the loan prime rate, which banks offer to their best clients, the new benchmark for pricing corporate loans. It works a bit like Libor, the key global rate that determines borrowing costs for everything from student loans to derivatives: Every month, 18 banks will submit their one-year loan prime rates to the PBOC, which will publish an average after removing the highest and lowest quotes.

It isn’t inconceivable that Chinese lenders, like their peers in the U.S. and Europe, would be tempted to collude and fix these rates to their advantage. But you need to have a market before you can manipulate it. In China, banks still don’t know how to price loans without hand-holding from the central bank.

A case in point: Lenders in the developed world use market-driven benchmarks to determine their loan rates. Banks in Hong Kong, for instance, base mortgage rates on one-month Hibor, the city’s main interbank rate. In the U.S., loans with longer duration are priced against Treasuries of the same tenor.

No such standards exist in China’s loan market. Some banks link their loan rates to Shanghai’s Libor equivalent; some to Chinese government-bond yields; and some to the savings deposit rates they offer. Still others equate their loan prime rates to the coupons of their own bonds, which means they don’t earn a penny from originating these loans. This dysfunction helps explain why the PBOC is asking these 18 banks to base their loan prime rates on their cost of borrowing from the central bank – China’s bank-loan market needs a pricing benchmark.

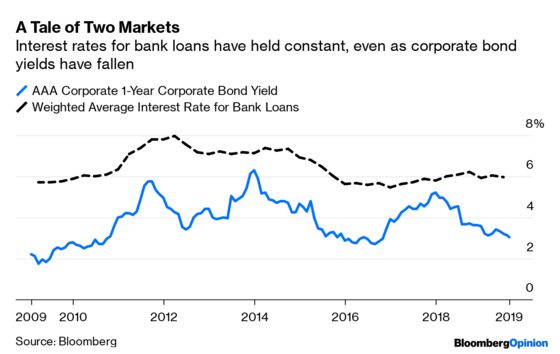

It’s also understandable that the central bank is frustrated with the status quo. Lenders have enjoyed cheaper funding in recent months, as the PBOC has pumped liquidity into the system through open-market operations. Yet they haven’t passed lower borrowing costs on to clients: Many banks simply apply the central bank’s policy one-year lending rate of 4.35%, tag on a small discount of, say, 10%, and blindly offer this minimum loan rate.

As a result, and much to the PBOC’s ire, interest rates for bank loans have held steady, despite a lower cost of borrowing in the bond and money markets. In its statement, the central bank warned against lenders setting “hidden floors” that would maintain lenders’ profit margins.

Expanding the list of banks to 18 from 10 – and including regional and rural commercial banks – will also create extra work for the PBOC. Whereas the Big Four commercial banks can rely on China’s thrifty households for deposits, regional banks have to seek funding from the interbank market. Bank of Xi’an Co., for instance, gets more than a quarter of its funding from short-term loans in the interbank market, compared with roughly 10% for China Construction Bank Corp.

This makes smaller banks’ access to funding much more volatile. If a lender such as Bank of Xi’an has a big repo loan due over the next week, wouldn’t its loan prime rate have to shoot higher? Bureaucrats at the PBOC will need to spend a good deal of time babysitting these small-town bankers – and teach them a thing or two about cash-flow management.

While it’s laudable that the PBOC finally took the long-awaited step – six years, to be exact – in interest-rate reform, one can’t help wondering if China’s bank-loan market is ready. What we will end up seeing is a lot of window guidance. The PBOC can only wish that Chinese bankers are as clever as those in London.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.