(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s central bank has acknowledged its monetary tools are insufficient. The most powerful ones are proving too blunt to drill through a hardening financial system.

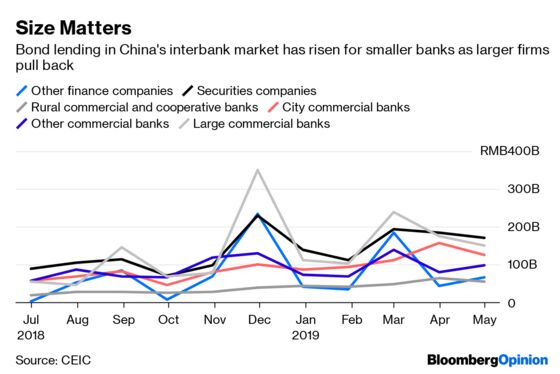

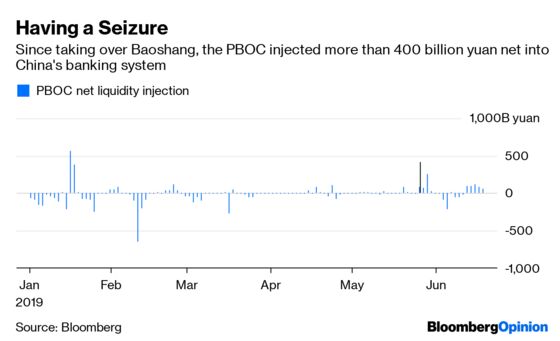

The country’s money markets have been shuddering since regulators took over Baoshang Bank Co. last month, despite initial assurances from the central bank and other authorities that they would maintain ample liquidity. While there has been little direct contagion, the seizure of the small commercial lender has hurt confidence. Funding costs for companies have shot up as large banks flinch from lending to some counterparties in the interbank market. For the first time in more than two decades, lenders face the prospect of defaults and haircuts on loans to other financial institutions, according to the Rhodium Group.

That means counterparty risk and solvency risk have arrived – together.

With liquidity-related stress spreading and interbank confidence waning, financial regulators are asking large brokerages to take over the role of providing financing to small and medium-size enterprises from lower-tier banks, the financial news website Caixin reported Tuesday. Big brokers have a better understanding of credit risk than obscure provincial banks in any case, the thinking goes. Securities companies have been asked to issue financial bonds eligible for use as collateral, increase quotas for short-term debt, and ease funding pressures for nonbank financial institutions.

The decision to turn to brokerages is stunning. For a start, brokers aren’t banks; they don’t have the ability to take deposits and don’t create money, so their ability to expand liquidity is far more constrained. Secondly, regulators are relying on a securities industry that only four years ago oversaw a spectacular boom and bust in China’s stock market that was fueled by excessive over-the-counter margin financing.

Meanwhile, the People’s Bank of China raised quotas on various financing facilities by around 300 billion yuan ($43 billion) to support small lenders. That comes amid anecdotal evidence that some companies are starting to shy away from accepting banker's acceptance bills (short-term debt paper) issued by some regional banks because of their operational risks.

In seizing Baoshang, regulators said that only corporate deposits and interbank liabilities of less than 50 million yuan would be fully protected. This has caused larger banks to avoid lending to smaller counterparties that are perceived as risky. Market participants have started sifting through the books of regional lenders to assess which may be next.

The situation has parallels with the freezing of the financial system that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, though the U.S. bank was far larger and more interconnected than Baoshang. In China's case, banks and companies tend to rely heavily on each other in the region where they operate. At the same time, the financial system has become far more complex, and there’s little clarity on the severity and extent of risks created by the proliferation of shadow-banking activities.

In theory, the central bank’s toolkit is vast: It includes standing lending facilities, medium-term lending facilities, targeted medium-term lending facilities, reserve ratio cuts and reductions in benchmark lending rates. This ever-expanding list has helped plug gaps, support companies in difficulty and keep China’s financial system functioning.

But the system’s ability to use money and credit productively has deteriorated as a bed of bad credit, off-balance-sheet lending and various other shadow banking activities has built up. This can be thought of as a hardened cement floor that prevents liquidity from seeping through.

As regulators pull out all the stops, it’s becoming increasingly evident that they’ve lost firepower. Part of the problem is that small lenders don't deal with the PBOC directly; they do so only via large banks.

The authorities’ confidence in brokers appears misplaced. By taking this step, the central bank is aiming to restore calm, but in the process it may have created far more risks than it’s prepared to handle.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.