(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China has plenty to gain from lending a hand to its friends battling the coronavirus in Africa. Contrary to some perceptions, that won't mean opportunistic grabs in oil, copper or arable land. The biggest prize for Beijing is political capital.

Sub-Saharan Africa faces its first recession in 25 years, and the continent as a whole is also grappling with the oil price crash and weakened currencies that have devastated state budgets. As a result of the Ebola outbreak that began in 2014, nations are better prepared than before. Still, health services are sorely inadequate, built around global financing and donor interests rather than coherent domestic policy, says Osman Dar, medical consultant and project director with Chatham House’s Global Health Programme. Barely a fifth of countries in Africa have free, universal care. The Central African Republic had three ventilators for a population of 5 million before the crisis; a handful of nations had none.

China is Africa’s largest trading partner and creditor, and Beijing moved swiftly to provide aid as the virus spread. It delivered tests, protective equipment and ventilators, assisted by the foundation of Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. co-founder Jack Ma. More remarkably, China endorsed a temporary freeze on debt payments agreed upon by the Group of 20 economies — unusual for a country that tends to prefer bilateral efforts. The scale and breadth of the current shock may have played a part in that decision, according to Lauren Johnston of the China Institute at SOAS University of London.

The soft-power push hasn’t gone smoothly. Parts of the continent’s civil society are still seething after videos circulated on social media this month showing discrimination against Africans in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou. They have been forcibly tested, barred from restaurants and even evicted from homes, causing public outrage back home. The heavy-handed measures to tackle a cluster of coronavirus cases in Guangzhou, which has a significant population of African traders and students, fed an underlying distrust and risked undoing the gains of mask diplomacy.

Beijing can still take advantage and obtain what matters to China: political allies in the United Nations, where Africa accounts for more than a quarter of member states, and clout that in turn influences its relations with great powers. Efforts have already paid off relative to far more expensive gambits, like its rapprochement with Pakistan. Given the pandemic, collapsing oil, a disinterested U.S. and a distracted Europe, it can do so more cheaply than ever.

To be clear, mineral riches and mercantile interests do matter. China’s companies are eyeing a young, growing population of 1.3 billion consumers. Shenzhen Transsion Holdings Co., a mobile-phone maker focused on Africa, priced its 2019 initial public offering in Shanghai at a price-earnings valuation twice that of Apple Inc. Telecom equipment maker Huawei Technologies Co. does brisk business there.

Even so, Africa represents less than 5% of Beijing’s $4 trillion of annual global trade. The real great game is about securing a Chinese candidate at the head of the Food and Agriculture Organization; getting a friendly one at the World Health Organization; and landing the country’s first overseas military base. Considering more countries attended President Xi Jinping’s 2018 African summit than the UN General Assembly held a few weeks later, there’s plenty to build on.

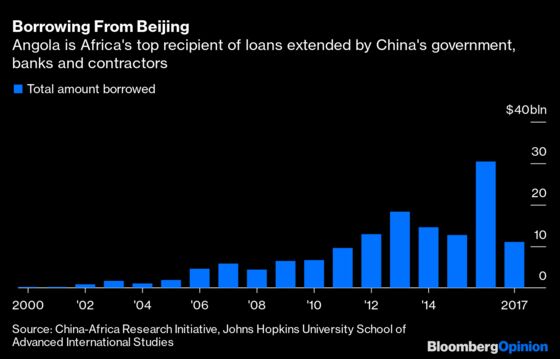

What happens next will center on debt. China’s government, banks and contractors extended more than $150 billion to Africa’s governments and state-owned enterprises between 2010 and 2018, according to the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University. Angola alone accounted for almost a third of that, CARI’s Deborah Brautigam wrote recently.

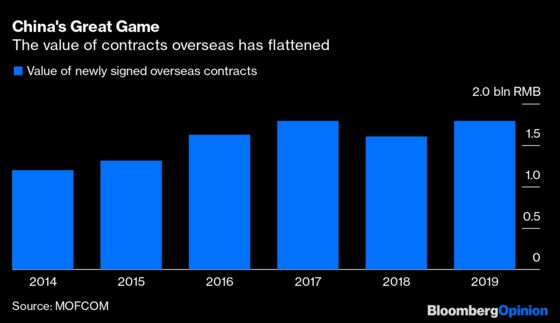

China forgives plenty of African loans, though usually small amounts. Relief is generally accompanied by more credit. It prefers to renegotiate, and will probably do so here. There won’t be a splurge. Chinese overseas loan-making plateaued or even dipped of late, and there’s little to suggest that caution will ease, even if state support for China Development Bank and Export-Import Bank of China means there is room for more.

Importantly, land grabs won’t be part of the equation. China has in the past used credit to get production rights, say, in Angola. But there is no substantial evidence, either in lending reviewed by CARI or in research done by Rhodium Group, that the country seizes strategic assets from debtors. Sri Lanka’s precarious levels of debt, which ultimately led to the concession of a strategic port, had deeper roots than China’s loans.

Take Zambia, currently battling Western miners and struggling with debt. The government may want a quick debt-for-equity fix, but it’s unclear Beijing would be so keen. Why trade a small economic gain for political ignominy? Even China’s commodity-backed loans have rarely been easy to act on.

Finally, negotiations won’t be easy. Despite talk that China is engaging in debt-trap diplomacy from U.S. Vice President Mike Pence and others, borrowers can and do push back, especially when new governments come in. Malaysia did in 2018, and the public anger of African ministers over Guangzhou points to similar agency.

Timing is more complicated. Africa needs cash, but big-bang assistance packages may have to wait. Beijing attributes huge importance to its African summit, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, due to be held next year in Dakar. At the 2018 edition, China announced $60 billion of aid and loans to great fanfare.

There are plenty of unknowns, not least around how China’s own faltering economy and domestic sentiment will affect its ability to lend. The UN has called for $200 billion for health assistance and economic help for Africa — a fraction of what the G-20 countries and China will spend at home. Aid could pay rich dividends. A friend in need, after all, is a friend indeed.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.