China’s Central Bank Going It Alone Spurs an Influx of Capital

PBOC is striking out on its own with signals of tighter monetary policy, widening a divergence with other large economies.

(Bloomberg) -- China’s central bank is striking out on its own with signals of tighter monetary policy, widening a divergence with other large economies that will shape global capital and trade flows next year.

With most of the world’s major nations still battling the pandemic and struggling to recover from deep recessions, China’s economy is on track to grow by about 2% this year and more than 8% in 2021.

That’s allowing People’s Bank of China Governor Yi Gang to turn his attention to a record debt burden, an issue that’s come into sharp focus following a spate of corporate defaults in recent weeks. He’s vowed to normalize policy, a signal to analysts he’ll seek to keep a lid on credit expansion.

The policy shift sets up China’s currency for more appreciation as international investors rush to buy the nation’s higher-yielding bonds, giving Beijing room to accelerate its financial opening to the world. But this influx of capital also risks turning China into a potential source of global volatility on a scale that its markets have never seen before.

More clues about the monetary policy stance are likely to come this week at the Communist Party’s annual economic work conference, with the toughness of language on debt control an indicator of how quickly policy makers will rein in credit growth.

Yi’s conservatism derives from two sources: sound economic fundamentals due to control of the pandemic, and policy makers’ conviction that loose monetary policy increases financial risk, said Zhu Ning, an academic at the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance, who has advised the central bank. With the economic recovery firmly on track, “sentiment is gradually shifting from more accommodating toward more risk averse,” Zhu said.

Few analysts expect the PBOC to hike its main policy interest rates, at least for the first half of 2021. But it can slow the growth in bank lending with other tools, for example by easing the pace of liquidity injections or targeting lower rates at banks which curb lending.

Crisis Role

China has previously played a key stabilizing role during crises in Asia. Its decision not to devalue the yuan during the Asian financial crisis more than two decades ago helped put a floor under the region. During the 2007-08 global financial crisis, it kept the yuan stable and propped up the economy with massive stimulus that fueled demand for commodities, boosting emerging economies worldwide.

“China always tries to be ‘the rock’ during crises and this means a stable renminbi,” said Michael Howell, founder of CrossBorder Capital Ltd., a boutique research firm, using an alternative name for the nation’s currency.

Just as China’s economic growth has a large impact on Asian economies through its demand for raw materials and intermediate goods for its vast manufacturing sector, the movements of its currency exert an increasing influence on the rest of the region too. That sets up China and its nearest neighbors for a repeat of their post financial-crisis outperformance.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

The People’s Bank of China appears to be starting a transition back to a neutral stance against a backdrop of a robust economic recovery. The PBOC in its 3Q monetary policy report re-surfaced the intention to align monetary (M2 and credit) and nominal GDP growth -- a key guideline in 2018 and 2019 that was absent in the 1Q and 2Q reports. In our view, this signals a tilt back toward avoiding risk accumulation from a pro-growth stance during the COVID-19 crisis.

-- Chang Shu and David Qu

For the full report, click here.

Economists at Pictet Asset Management argue that Asia has evolved into an “RMB bloc,” driven by increased trade-settlement in renminbi. The bloc represented some 23% of world gross domestic product in 2019, compared with just 5% in 2006, they estimate.

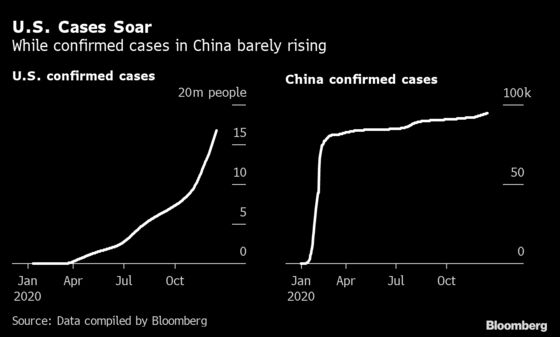

At the heart of the divergence in economic performance and policy approach is the success in preventing large-scale outbreaks of coronavirus in the second half of this year, allowing the real economy to return to growth. China recorded fewer than 2,600 new Covid-19 cases in the past month, most of which were imported, compared with more than 5.5 million in the U.S., according to latest data from John Hopkins University.

“2020 has really been a tale of two worlds: a world where Covid is contained versus a world where Covid has not been contained,” said Teresa Kong, a portfolio manager at Matthews International Capital Management LLC in San Francisco. “China is definitely in the world of successful Covid containment. As such, we need to look at the Chinese monetary policy in that context.”

Yukon Huang, a former World Bank head in China who is now a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Asia Program, says China’s outperformance through the Covid shock means it’ll come out a year or two ahead of most Western economies.

“They have the potential to go out of crises stronger than others,” he said. That’s because “China’s rebound wasn’t propped up by a fiscal and monetary push like in the West. The consumption recovery is built on production, which is a more sustainable base.”

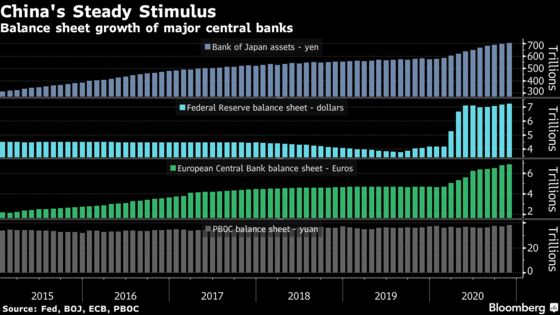

The contrast with the rest of the world appears starkest when looking at central bank balance sheets. While the PBOC has increased its assets by less than $360 billion this year, central banks in the U.S., U.K., euro zone, and Japan expanded theirs by a combined $5.6 trillion, with the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet alone expanding by $3 trillion from early March to mid-June.

“PBOC policy divergence is indeed striking and the most significant in recent history,” said Jerome Jean Haegeli, chief economist at Swiss Re AG in Zurich, and previously of the International Monetary Fund.

One reason it hasn’t leaned on its balance sheet as much as global peers is the PBOC largely handed the task of increasing money supply and lowering interest-rates to state-owned banks. It cut bank reserve-requirements, meaning they had more cash to dole out in loans.

With the economy growing again, policy makers have signaled they want a more sustainable pace of credit expansion. By contrast, the Fed, European Central Bank and Bank of Japan have all announced plans to maintain and step-up stimulus into the next year.

“Advanced economy central banks will try to use negative real interest rates and inflation to erode the real value of their sovereign debt,” said Andrew Sheng, chief adviser to China’s Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. “This is why real money flows will go to the economies that show growth, higher productivity” and steady monetary and exchange rate policy, he said.

The difference in yield between Chinese government bonds and U.S. Treasuries is already near record levels, with many market players expecting the gap to widen further next year.

Beijing allowed consistent appreciation of its currency from 2010-14, an era that saw increasing capital account liberalization and expectations for the yuan’s greater global role. That came to a stark end in 2015, when a sudden devaluation spurred capital outflows. Geoff Yu, a market strategist at Bank of New York Mellon, said policy makers have learned from that mistake.

China’s spillovers to the global economy in past years have largely been through “real” channels such as its demand for raw materials and intermediate goods that feed its supply chain. Now, as authorities carefully open up, there could be much greater “financial” spillovers to the rest of the world, according to Mark Sobel, a former U.S. representative at the IMF who’s now at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a policy think-tank.

The PBOC has argued that its cautious approach leaves it with more room to respond to future shocks. “The basic characteristics of China’s economic potential, strong resilience, large room for maneuver, and multiple policy tools have not changed,” it wrote in a financial risk report released in November. It has frequently warned of the negative effects of excessively low interest rates.

“I’ve called the PBOC the ‘Bundesbank of Asia,’ to convey the point that it is one of the very few central banks left that have a multi-cycle perspective,” said Stephen Jen, who runs Eurizon SLJ Capital, a hedge fund and advisory firm in London. The central bank believes that “policies ought to be designed to not only deal with the current cycle but also the next cycles.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.