China’s Brief Trial of Two Canadians Tightens Vise on Trudeau

China’s Brief Trial of Two Canadians Tightens Vise on Trudeau

(Bloomberg) -- After short trials, two Canadians remain imprisoned in China, trapped in a geopolitical squeeze between two superpowers and a Chinese billionaire’s daughter.

Following more than 800 days in jail, the trials of Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig were over within hours with no verdicts announced. The legal proceedings have exposed how much Canada has at stake and the scant leverage of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Canada is “deeply troubled by the total lack of transparency,” Foreign Affairs Minister Marc Garneau said Monday in a statement. “The eyes of the world are on these cases and proceedings.”

The men were detained in China in December 2018, days after Canada’s arrest of Huawei Technologies Co. executive Meng Wanzhou on a U.S. handover request. The plight of the “two Michaels,” as they’re known, has left the nation aghast, hardening public opinion against Beijing and putting increasing pressure on Trudeau to take a tougher stand.

China has denied targeting the men in retaliation for the arrest of Meng, the eldest daughter of Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei, but has repeatedly made it clear their fates are linked. The impasse has plunged bilateral relations into their darkest period in decades.

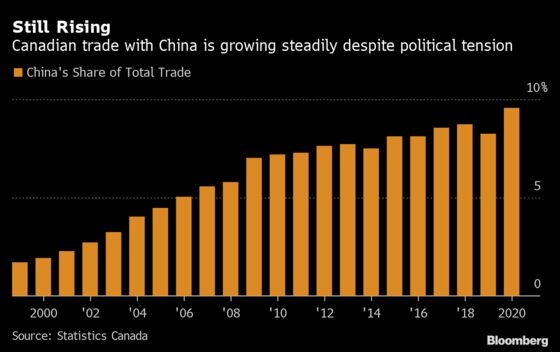

The Asian nation is Canada’s second-largest trading partner and its share of Canadian trade hit a record high in 2020, despite the diplomatic crisis. In an opinion piece published in the Globe and Mail newspaper the day of Spavor’s trial, China’s ambassador in Ottawa underscored how Canada’s long-term economic prospects hang in the balance. “Board the fast train of China’s development,” Cong Peiwu urged Canadians. “Promote win-win cooperation between our countries.”

China’s terms have long been clear: release Meng and stop talking about its treatment of Uyghurs and Hong Kong pro-democracy activists. Canada has pushed back, with the House of Commons backing a motion to label China’s actions in Xinjiang province as genocide.

“China needs to understand that it is not just about two Canadians,” the prime minister told reporters on Friday. “It is about the respect for the rule of law and relationships with a broad range of Western countries that is at play with the arbitrary detention and the coercive diplomacy they have engaged in.”

Yet expressions of solidarity have been both poignant and futile. Western diplomats gathered outside both courts in a public show of unity but were blocked from entering.

‘Bargaining Chips’

Prosecutors in New York seek Meng on fraud charges, alleging she misled banks into handling Huawei transactions that violated U.S. sanctions on Iran. The Shenzen-based technology giant’s chief financial officer denies any wrongdoing, and her extradition case is still going inside a British Columbia courtroom.

“We are in this situation because we fulfilled an extradition treaty with our closest ally,” Trudeau told Bloomberg News in an interview last month. The election of U.S. President Joe Biden sparked hope for an end to the stalemate, especially after he called for Kovrig and Spavor’s release, saying “human beings are not bargaining chips.”

From Canada’s perspective, the simplest solution would be U.S.-led -- if not dropping the extradition request, then striking some sort of deal with Meng for lesser charges. However, last week’s high-level meetings between the U.S. and China proved acrimonious, and Canadian officials are concerned tension could stall any progress in the legal cases.

Another possibility would be a Canadian court verdict in Meng’s favor, though history suggests the odds of that are low. Canada has refused or discharged about 1% of U.S. extradition requests since 2008. That’s only fractionally better than the prospects of the two Canadians in China, where the conviction rate is 99.9%, according to human-rights group Safeguard Defenders.

Beyond that statistical similarity, the experiences of Spavor, Kovrig and Meng couldn’t be more different. Michael Spavor’s trial in a private Dandong courtroom last week lasted about two hours and Kovrig’s began and ended Monday.

By the time Meng’s current stretch of extradition hearings wrap up in May, her defense will have had more than 80 days in open court, covered exhaustively by international media.

A single government-approved defense lawyer was hired for each of the Michaels by their families but access to those lawyers has been limited, particularly for Spavor. Meng has a phalanx of North American law firms working on her case -- so many that on some days there wasn’t room in the main section of the Vancouver courtroom to hold all her lawyers.

Over the past two years, Meng has often been accompanied to court by a throng of Huawei colleagues, Chinese consular officials, and her husband. Spavor and Kovrig have had only rare contact with their families, by letters or phone calls, and Canadian consular officials were denied access to their trials. Kovrig has described the “gray, grinding monotony” of a windowless concrete cell.

Meng lives under house arrest at her C$13.7 million ($10.9 million) Vancouver mansion but her bail terms allow her to roam a roughly 100-square-mile patch of greater Vancouver during the day, accompanied by court-appointed private security and a GPS anklet. She shops at high-end Vancouver boutiques and spent Christmas Day at a restaurant that catered exclusively to her party.

While an initial decision on Meng’s extradition is expected some time after May, her family’s wealth could allow her to keep fighting for years from her Vancouver mansion. Ultimately, if she’s handed over, she can start a fresh legal battle in a U.S. trial.

Whether Spavor or Kovrig would be allowed to appeal a guilty conviction would depend on details of their conviction. Either way, they’d be immediately transferred from a detention center to a prison and would have to wait out the process there. People convicted of serious violations of the section of law cited by Chinese authorities face 10 years to life in prison.

The situation is urgent, Kovrig’s wife, Vina Nadjibulla, said in an interview last week. “All tools of diplomacy now need to be mobilized and put to use to end their unjust detention and suffering as quickly as possible.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.