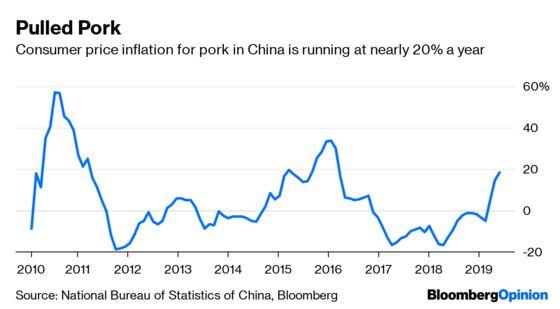

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The African swine fever epidemic has pushed up Chinese wholesale pork prices by a quarter since the start of March. As much as a fifth of the country’s herd has been culled. So why won’t Beijing import American meat?

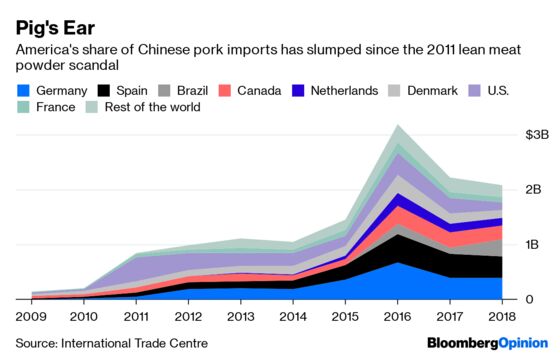

The prospect of replacing all those cuts lost to the cull would represent “the single greatest sales opportunity in our industry’s history” if China only removed import tariffs, according to the National Pork Producers Council. Those levies now stand at 62% because of the trade war with Washington. U.S. piggeries can only look with envy to less politically exposed European pig farmers, who are currently winning the battle to plug China’s pork gap.

It’s not just protectionism that’s blocking U.S.-China swine trade, though. Any hopes of larger agricultural purchases from a trade truce at the Group of 20 meeting in Osaka need to reckon with the fact that reducing levies won’t be enough to make China buy U.S. pork.

The fundamental reason comes down to ractopamine, a feed additive that helps pigs bulk up with more lean meat in the final weeks before they’re sent for slaughter. It’s fed to between 60% and 80% of American pigs but is banned by China, Russia, and the European Union, citing concerns over its effect on human health.

Even before the current trade tensions, that’s caused problems for American piggeries, with the country’s share of China’s imports falling from almost 50% in 2011 to less than 13% in 2016.

It’s common for health and sanitary regulations to be used as cover for protectionism in agricultural products, but in China’s case there are genuine reasons for the restrictions.

Along with tainted baby formula and faulty vaccines, one of the country’s biggest product-safety scandals in recent decades involved the illegal use of so-called “lean meat powder,” a group of black-market additives including ractopamine and the asthma medication clenbuterol. Almost 1,000 people were arrested in a 2011 government crackdown on the clenbuterol industry. Shares in Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development Co., the parent of the world’s largest pork company, WH Group Ltd., fell by nearly a third in the month after the drug was found in its products that year. Others were arrested for involvement in the ractopamine trade.

The ripples of the lean meat powder scandal have reverberated ever since. WH Group’s 2013 takeover of the biggest U.S. pork producer, Smithfield Foods Inc., which had been positioning itself as a supplier of ractopamine-free meat, came just months after Beijing started requiring that American pork imports be certified without the additive.

The same concerns fueled China’s decision last month to ban Canadian meat imports after ractopamine was found in a shipment of pork tongue.

There’s ample reason to worry about a political angle to that spat, given China’s dispute with Ottawa over the arrest of Huawei Technologies Co. Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou. Beijing had previously imposed restrictions on Norwegian salmon after the 2010 Nobel Peace Price was awarded to dissident Liu Xiaobo.

At the same time, the seriousness with which Canada’s government is treating the case indicates that it sees Beijing’s restrictions as a genuine human-health measure, rather than just a protectionist cudgel. China certainly isn’t the only country stopping trade for this reason: Russia barred Brazilian meat in 2017 over ractopamine, too, and Vietnam has been tightening its regulations in recent years as it’s started to depend on pork imports.

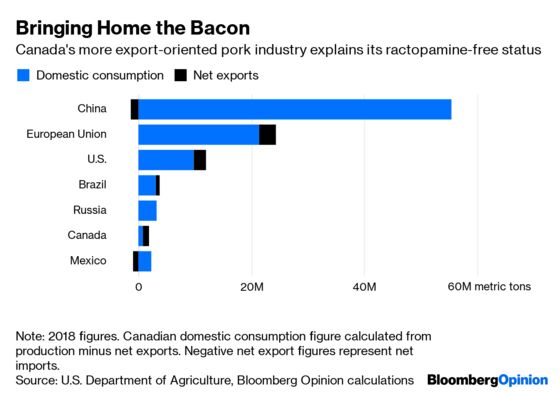

The problem for U.S. farmers seeking Chinese buyers is that the benefits of giving up ractopamine don’t seem to outweigh the costs. Growth-enhancing feed additives are so central to the U.S. trade that piggeries not using them struggle to price their bacon, sausages and ribs at a level that will win the mass market. Unlike Canada, which exports more than half its pork, the U.S. consumes four-fifths of its meat at home, and key export markets such as Japan, South Korea and Mexico don’t restrict ractopamine.

Arguments about whether customs rules are protectionism or necessary health and biosecurity measures are some of the most bitter and protracted disputes in trade. New Zealand apples were barred from Australia for 90 years until the World Trade Organization overturned the ban in 2011.

The fights over ractopamine at the WTO have been going on for a decade, and will probably continue for many years to come. American farmers wanting to carve off a slice of China’s pork market will be better off ensuring they can certify their own supply chains as ractopamine-free, rather than waiting for salvation from tariff reductions.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.