China Returns to Old Construction Playbook to Boost Growth

China is returning to its stimulus playbook, going local.

(Bloomberg) -- China is returning to its stimulus playbook, with local governments borrowing a record amount to spend on infrastructure this year to drag the economy out of its coronavirus- induced slump.

In past stimulus cycles -- such as after the global financial crisis -- China splurged on roads, airports, and railways, and racked up huge debt. For the past few years, much of this spending has been funded by bonds tied to projects that are meant to make enough money to repay the debt.

The problem is that much of the money looks to be going to build the same kind of construction projects as in past years, which struggle to generate sufficient revenue and end up adding to the debt of local governments. The effect of this spending has also been slow to appear, with infrastructure investment at the end of July still below where it was the same time last year.

“The central government wants the local administration to speed up bond issuance and granted them large quotas,” according to Susan Chu, senior analyst at S&P Global Ratings specializing in local government credit ratings. “However, it takes time to start a project and to spend the money” and it’ll take months for the effects to appear, she said.

Local governments must sell 3.75 trillion yuan ($550 billion) worth of so-called “special bonds” by the end of October, with 2.27 trillion yuan issued by the end of July. That’s already more than in the whole of 2019, and the government is hoping this will jump-start private spending and investment.

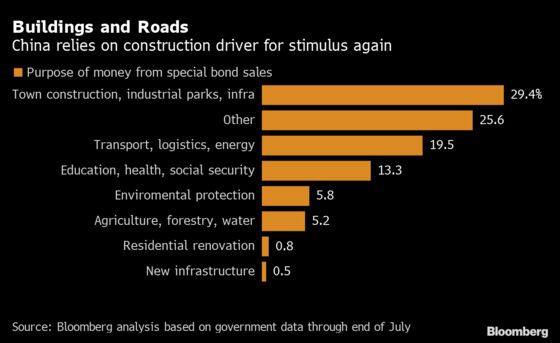

Almost 30% of the money through the end of July is earmarked for industrial parks, town construction and infrastructure, while another 20% is going to be spent on transport, logistics and energy projects, according to Bloomberg’s analysis.

“It’s getting more difficult for local governments to find qualified and profitable projects” to use this money, according to Betty Wang, senior economist at Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd in Hong Kong. “That’s why the funds were also used to finance land reserve and shanty town projects last year.”

Local governments struggled in the past to find profitable projects to use this money, with a lot of the borrowing in 2018 used to buy “land reserves” for future projects. That was banned and the central government is encouraging local areas to use some of the money for high-tech projects such as 5G infrastructure, which may provide better returns.

Late in July, the Finance Ministry gave provincial governments some leeway in how they used the funds. If a project isn’t ready to start, the borrowed money can be used for other investments that are, the ministry said.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say...

The lack of appropriate investment projects may be a hurdle, but the central government has allowed local governments wider latitude in how they use the funds, including as source for capital injections for local banks. This should encourage local governments to issue bonds. Debt sales should start to accelerate from August.

David Qu, Bloomberg Economics

Governments will need to find even more new projects to invest in quickly, as another 1.5 trillion yuan worth of bonds needs to be sold from the start of August through the end of next month, according to the Finance Ministry.

Revenue Sources

Many of these projects rely on land sales to repay investors, but a slowing economy will likely hit demand for land and put pressure on prices, making it even harder to service these debts.

With the budgets of China’s local governments already under pressure from a combination of tax cuts and the need to raise spending to deal with the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, the higher debt levels from this borrowing will just add to their problems in the long term.

“We are concerned that local government debt ratios are still on the rise,” said to S&P’s Chu. “It’s very rare to see a local government work out the entire life cycle of a project, including its cash flow, from the start of the project to the end.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg