(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Everyone knows China’s stock markets aren’t for the faint-hearted. But plain vanilla assets can be equally scary.

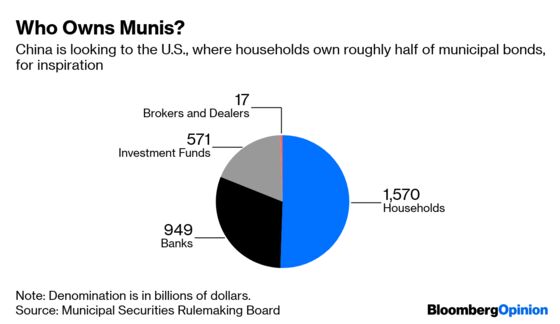

This year, China has been opening up its municipal bond market, once the exclusive domain of banks, to retail investors. With a sweeping stimulus underway, there’s good incentive to do so: Someone has to buy the bonds to fund it. There’s also a tested model in the U.S., where households own roughly half of their local governments’ bonds. These assets are perceived as ultra-safe, even yawn-worthy. Surely China could emulate a similar system, or so the thinking goes.

Beijing has been eyeing retail money for some time. Zhou Xiaochuan, former governor of the People’s Bank of China, floated the idea as early as 2012, arguing that local governments would have more budgetary discipline if their bonds were publicly traded. Yet any effort to tap this deep pool of investors never gained momentum.

Now Beijing has opened the floodgates, with plans to sell 2.15 trillion yuan ($320 billion) of special-purpose municipal bonds this year to fund infrastructure projects, up from 1.9 trillion yuan issued in 2018. According to the new rules, no prior investing experience is necessary to buy in, as long as notes are AAA rated. Since almost all munis have a pristine score — except for a few basket cases, such as Inner Mongolia — practically anyone can invest. The minimum subscription is just 100 yuan ($15).

This has set off retail frenzy. Beijing’s 3.25 percent, five-year bonds were gobbled up. The coupon on a three-year bond issued by the east coast city of Ningbo was set at 3.04 percent, just 29 basis points above the benchmark deposit rate of 2.75 percent.

But there are several red flags.

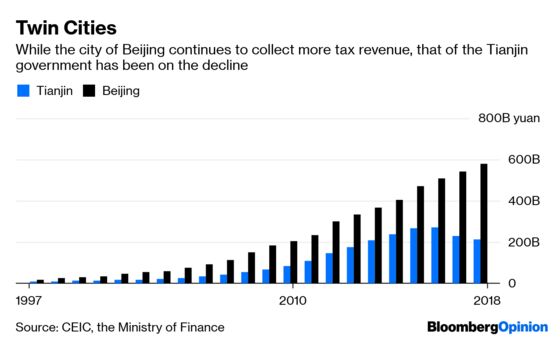

First, not all munis are created equal, even if the market is treating them that way. The Ministry of Finance gives very strict guidance on new issues: Local governments are advised to sell their bonds at only 25 basis points to 40 basis points above the sovereign issue of the same tenor. Some have priced even tighter. Beijing’s recent 10-year bond, for instance, offers a 3.33 percent coupon rate, 18 basis points above the sovereign. An issue from its neighboring city of Tianjin pays 3.39 percent, just 6 basis points higher.

Yet the finances of Beijing and Tianjin couldn’t be more different. Last year, the capital city’s tax revenue rose 6.5 percent to 579 billion yuan, accounting for roughly 73 percent of its total cash inflow. Tax revenue in Tianjin, on the other hand, tumbled 8.9 percent.

The Ministry of Finance has a roundabout way to stop this discrepancy from causing widespread problems: prevent troubled local municipals from flooding the market with new notes. Tianjin had room to raise only 8 billion yuan last year, a quota it hit quickly. Still, investors aren’t being compensated for holding this debt.

Even more alarming is that all of these so-called special-purpose bonds are excluded from municipalities’ balance sheets; in other words, they don’t have the state’s explicit guarantee. In theory, cash flow from underlying projects can cover interest and principal payments, so the credit profile of these bonds is independent of a local government’s fiscal situation.

Already, some new issues are relying on grand assumptions. Shandong province, for instance, just sold retail investors 220 million yuan of munis at 3.8 percent to improve one rural county’s infrastructure. To repay its bondholders, the province will sell land from that county, whose value is expected to grow at 6.4 percent per year over the next five years. That’s rather ambitious in a country whose property sector is overrun with supply in smaller cities.

Lately, China’s intellectuals have been debating “fiscal federalism,” the thinking that local governments should be empowered to collect and spend tax revenue. Currently, the flow is the opposite: Municipalities do all the dirty work of generating cash, but remit those funds to the Ministry of Finance, which then decides how to dole it out. Without such largess, even cities as wealthy as Beijing would be deep in the red. That’s why anyone daring to buy munis must have faith these handouts will keep coming.

China has been talking about fiscal reform for decades, yet nothing has come of it. Until true market forces take hold, mom-and-pops are better off staying away from the investments closest to home.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.