China’s Central Bank and the Fed Look More Alike

On a deeper level, the PBOC has evolved significantly as an institution in the way it interacts with investors and the public.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- So much for the great divergence between economic systems led by the U.S. and China. In the monetary arena, they look more alike than at any point in recent years.

Both the Federal Reserve and the People's Bank of China end 2019 signaling interest rates will stay at current levels with a bias toward cuts, if they have to do anything. Each is concerned with too-low inflation. They took different journeys to get here: The Fed cut rates three times before taking a breather, while China refrained from trimming its benchmark rate despite predictions it would.

On a deeper level, the PBOC has evolved significantly as an institution in the way it interacts with investors and the public. It’s not some impenetrable fortress of authoritarian financial diktats. Chinese central bankers give frequent speeches and interviews, issue press releases and publish a fairly detailed quarterly Monetary Policy Report.

This is more than public relations. Communications have become an increasing part of the central bank armory across the globe in the past two decades, coinciding with China’s rise. The PBOC has become so visible, and its decisions to the world so critical, that a research paper from the Reserve Bank of Australia should be compulsory reading for anyone interested in international economics.

The paper, published last week by Bradley Jones and Joel Bowman, says that while the PBOC increasingly resembles other central banks, full convergence is unlikely, due largely to the lack of political independence. It’s not an ideological point. The bank's place in China's state machinery and policy spectrum means there are important things it can do in only limited ways and other areas it can't address at all.

Forward guidance is hard. Quarterly forecasts stretching out to years, de rigueur among central banks, aren't published. When and if China does cut its benchmark rate, we almost certainly won't know the date and time in advance. Needless to say, there isn't anything remotely like Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s testimonies to Congress or Bank of England Governor Mark Carney's testy exchanges with lawmakers.

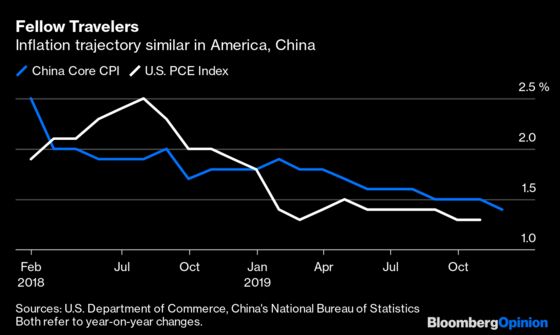

None of this is intended by Jones and Bowman as a knock on the PBOC or China. One paradoxical observation they make is how much China's inflation performance resembles the advanced economies. The trend lines are similar and the PBOC takes price stability seriously even if it can’t enforce its will autonomously. The outcomes are broadly the same, even if, as the authors note, they “have been generated in very different institutional contexts.”

How similar are they? While China’s consumer inflation accelerated to a seven-year-high in November, largely owing to a surge in pork prices, underlying price pressures are faint. Core inflation rose just 1.4% and has been below 2% for more than a year. Not that different to the Fed's ongoing challenge to get its preferred inflation gauge, now at 1.3%, up to the 2% target. Consistent undershooting was the rationale for the European Central Bank to return to quantitative easing.

Jones and Bowman also discuss how the PBOC is enmeshed in the state's broader policy apparatus. When the bank acts, it’s always consistent with broad national policy objectives, often because sign-off is required from the State Council, akin to China's cabinet. It begs the question: Does this make the outcome necessarily inferior? While few practitioners in the developed world want to downplay the idea of central bank independence, there's a lot to be said for policy levers pulling in the same direction.

Independent central banks have made mistakes. There’s no monopoly on wisdom in Washington, Frankfurt or London. Monetary high priests outside China regularly beseech fiscal and regulatory authorities for help in generating growth. For a long time, the Fed wasn’t the gold standard on communications and transparency. Press conferences only came along in 2011, and only this year have they followed every rate decision. The Fed didn’t have a numeric inflation target until 2012.

Amid the cacophony of commentary this year about technology rivalry and trade breakdowns and makeups, it’s important to see where China and the West are getting closer – even if they aren’t intimate.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.