(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Zambia has been careening toward a debt debacle for months, even years. Now it has become the first African nation to default on sovereign payments since the pandemic began. That’s bad news for everyone involved, from the bondholders who refused to agree to a standstill, to Chinese lenders, multilateral institutions and the government. A protracted restructuring lies ahead. More transparency might have helped all parties, including Beijing.

Emerging markets have been battered this year, as the price of oil and other commodities came crashing down once coronavirus took hold. Tourism revenue dried up, while lockdowns and other costly restrictions were imposed. Sub-Saharan Africa will see its economy shrink 3.3% in 2020, according to the World Bank, the region’s first recession in 25 years. Enthusiastic borrowers like Zambia have come under severe pressure. In October, Lusaka missed a $42.5 million interest payment on a dollar-denominated bond, prompting a grace period to kick in. That expired Friday, giving bondholders the right to demand immediate repayment.

Africa’s second-largest copper producer has been closely watched as a test case in the global post-coronavirus debt mess. With $3 billion of outstanding eurobonds, it had sought shelter as part of the Group of 20’s debt service suspension initiative, or DSSI, for low-income countries. Bondholders dug in their heels. Finance Minister Bwalya Ng’andu said Friday the country had no alternative but to “accumulate arrears.”

Much of the problem, apart from the absence of a convincing government plan to turn the country’s fortunes around, is that the debate has been held in the dark. Private bondholders are jostling with China and other creditors, but there is little light shed on the specifics of loans and negotiations, on either side. It has left all involved with few facts and plenty of suspicion. China Development Bank, or CDB, for example, agreed to a repayment deferral with Zambia in October — but no details were provided.

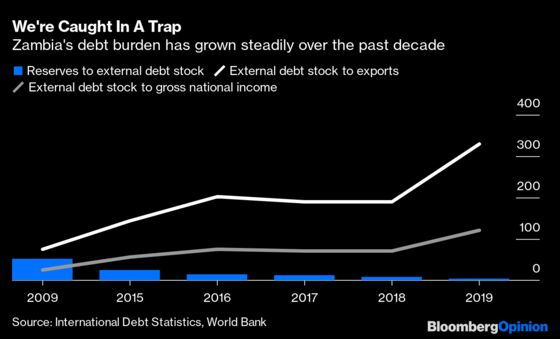

Not all African countries are in such an acute predicament. Zambia’s leaders bear responsibility: The debt burden has increased steadily since 2012, thanks to expansionary fiscal policy and often profligate infrastructure spending, at a time when growth was unimpressive and the currency weakening. The International Monetary Fund warned about the risk of debt distress well before Covid-19. The ratio of debt to gross domestic product could exceed 110% this year, according to forecasts from rating agency Moody’s Investors Service.

But while the protagonists of this crunch have been bondholders, who account for a much larger chunk of African debt than even a decade ago, it is China that has loomed over their discussions. Chinese credit accounts for more than a quarter of Zambia’s external public debt, and private bond investors, themselves hardly paragons of transparency, want more information on Lusaka’s dealings. They fear the government will put them off, but pay back Beijing.

There has arguably been little incentive for China to provide those answers. Disclosure comes with risks, and China may not even have a centralized idea of exactly how much is owed, given the multiple entities involved. It doesn’t want loans from CDB, a policy bank turned commercial lender, to be considered bilateral. It may want to avoid giving other creditors an advantage, and is wary of setting precedents. Clarity abroad may concern citizens who want to see cash deployed at home instead.

It’s also possible that even with more transparency on China’s debt, Zambia might not have avoided Friday’s outcome, as Eric Olander of the China Africa Project put it to me. The picture might ultimately have looked worse.

Longer term, though, a little clarity could mean diplomatic gains, even if Beijing loses some short-term negotiating edge. As the continent’s biggest lender, the bigger prize for China has always been political. It’s worth considering that oft-cited examples like Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port or even a power grid deal in Laos, where China has ended up with equity, are often convoluted and the product of circumstance, rather than concerted policy. What happened in Laos would be far more difficult to pull off in Africa, where pushback against China has been stronger, and media vocal. In any event, China prefers access to revenue streams.

Write-offs are unlikely to be significant, so with more renegotiations on the cards for Beijing across Africa — Rhodium Group estimates at least 18 processes have taken place in 2020, with 12 countries still in talks at the end of September, covering $28 billion of loans — a more limpid China could avoid being accused of engaging in blunt debt trap diplomacy. It’s not that there isn’t untoward behavior and reckless lending; It’s that accusations may overplay the reality.

A little clarity, perhaps even increased participation with global debt restructuring efforts, could achieve another goal too. It might increase pressure on Western private lenders and bondholders to do the same.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Clara Ferreira Marques is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities and environmental, social and governance issues. Previously, she was an associate editor for Reuters Breakingviews, and editor and correspondent for Reuters in Singapore, India, the U.K., Italy and Russia.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.