(Bloomberg Opinion) -- You only learn who’s been swimming naked when the tide goes out, as Warren Buffett observed in 2008. This earnings season, we’ll get to see who’s been skinny-dipping in China.

Banks and asset managers in the world’s second-largest economy are notoriously slow to acknowledge investments that have gone bad. But if they have a stock listing in Hong Kong, they’ll be forced to recognize losses earlier in the credit cycle under a change in accounting rules that took effect last year.

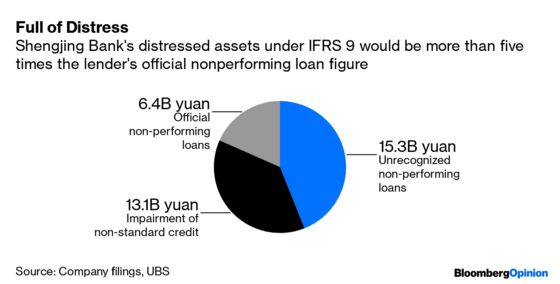

International Financing Reporting Standard 9 has already forced companies to disclose billions of dollars of soured credit, and the impact is set to become even more severe. For instance, distressed assets at Shengjing Bank Co., the largest lender in the troubled northeast province of Liaoning, would have totaled 35 billion yuan ($4.9 billion) under IFRS 9 last year, according to UBS Group AG estimates – more than five times the official nonperforming loan figure.

The accounting rule change is combining with China’s economic slowdown to magnify losses this year. Under IFRS 9, any change in macroeconomic fundamentals such as GDP growth or unemployment forecasts can prompt auditors to adjust their models and demand much bigger capital buffers for expected loan losses. “It is no longer necessary for a credit event to have occurred before credit losses are recognized,” explained China Huarong Asset Management Co., the state-owned and Hong Kong-listed bad debt manager, in its 2018 filing. Huarong posts first-half earnings Wednesday.

The first read isn’t good. China Shandong Hi-Speed Financial Group Ltd., the financing subsidiary of a state-owned giant that builds roads, bridges and ports for the northeast province of Shandong, warned of a substantial loss this month because of a decline in the fair value of a financial asset. Shandong Hi-Speed Financial is also due to release results Wednesday.

Or consider Bank of Jinzhou Co., another regional lender in Liaoning that received a partial bailout last month. Eight months into 2019, Jinzhou is still unable to release its 2018 annual report, in part because of more stringent requirements under IFRS 9 for the disclosure on non-standard credit products. Last week, the bank issued a profit warning, forecasting a net loss of as much as 1 billion yuan for the first six months, compared with net income of 4.3 billion yuan a year earlier. Jinzhou is scheduled to report Friday.

Bank of East Asia Ltd., a Hong Kong-based lender with extensive business in China, said last week that first-half profit tumbled by 75% as impairment losses jumped 18-fold from a year earlier to HK$5.1 billion ($650 million). Loans classified as “Stage 3,” accounting jargon for in default, soared fourfold from the end of 2018.

Defaults in themselves aren’t so scary if you can claw back money in recovery, as I’ve written. The trouble is that in China, that’s difficult. We can see this in Bank of East Asia’s disclosure: Only 37% of loan advances in mainland China are covered by collateral, versus 81% in Hong Kong. In other words, when China’s economy slows, lenders not only have to raise their estimated probability of non-payment but must also pencil in higher losses in the event of default.

The deterioration of lenders’ books isn’t surprising, considering the macro backdrop. At April’s Politburo meeting, key phrases such as “deleveraging” started to reappear as Beijing renewed attempts to rein in China’s housing bubble. Shadow banking, an important funding channel for private businesses, has once again been scaled back. In these circumstances, it’s natural that China Inc. has become more distressed and asset writedowns are climbing. IFRS 9 is simply shining a light in that dark corner of bank balance sheets.

Critics say the accounting change has made financial firms’ earnings more volatile. To which defenders might reply: Isn’t that the point? Banks’ loan books should be the pulse of the economy. Looking at the state of China’s health, we should get ready for more billion-dollar writedowns.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.