Central Banks Step Up $5.6 Trillion Bond Binge Despite Doubts

Central Banks Step Up $5.6 Trillion Bond Binge Despite Doubts

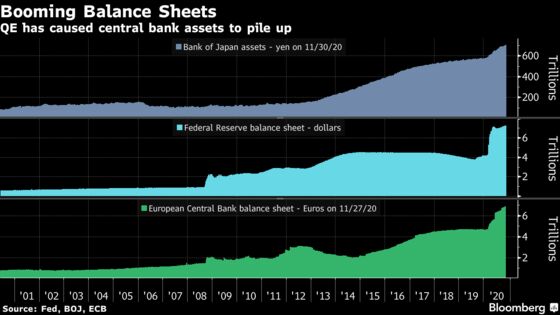

(Bloomberg) -- Global central banks are embarking on fresh waves of bond-buying to fight the fallout from the pandemic, despite mounting claims that the once-mighty policy is losing its power to boost the economy.

The U.S. Federal Reserve, Bank of England, Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank have splurged $5.6 trillion this year alone on quantitative easing, according to Bloomberg Economics. The ECB is expected to increase its own purchase plans by as much as 500 billion euros ($605 billion) when it meets on Thursday.

Central banks’ own research departments regularly produce work showing QE has stabilized markets, boosted growth and driven faster inflation. Outside though, there’s far less certainty that those benefits will persist after years of monetary stimulus following the global financial crisis more than a decade ago.

“QE works particularly well during periods of market disturbances, but it won’t be able to do much at this point for growth and inflation in the absence of fiscal policy,” said Peter Praet, former ECB chief economist and an architect of Europe’s own large-scale bond-buying plan that began in 2015.

| Central Bank Action |

|---|

|

Massive purchases of public and private debt pump money into the financial system with the aim of lowering the rate of interest on assets. With their traditional tool of official rates now close to or below zero, QE has become the primary stimulus tool for many central bankers.

Recent work by Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research economist Ramin Toloui argues that QE has been effective in lowering bond yields and it has “reshaped market expectations of how the Fed would behave in the future.”

Still, the further bond yields drop, the greater the risk of unintended consequences. If the aggressive monetary policy of the past years has run its course, it may be harmful to continue relying on it.

Former U.S. Treasury secretary Lawrence H. Summers and former Council of Economic Advisers chair Jason Furman wrote in a Nov. 30 paper that much more robust action by finance ministries is needed instead.

“How much investment would be done at a 0% 10-year Treasury rate that would not be done at a 1% 10-year Treasury rate,” they wrote in the Brookings Institution article. “The consequence, if not compensated for by more active fiscal policy, would be longer and more severe recessions.”

| Selected Research |

|---|

|

Another central function of QE, encouraging investors to take riskier bets, is losing its potency. Depressed yields have spread to assets with ever-longer maturities -- further along the yield curve. That weakens the link between risk and reward.

The BOJ has long been a trailblazer for QE. But even after piling up assets larger in scale than the size of its entire economy, it has failed to generate the stable inflation it sought. Its switch to yield-curve control in 2016 was in part a recognition that it had to adjust its approach to stop yields falling too low.

That’s an issue Europe is now grappling with. Joseph Gagnon, an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, says the ECB is essentially “out of room” for QE. All of of Germany’s sovereign debt -- typically considered the region’s safest asset -- has a yield below zero, meaning investors lose money by holding it.

“There’s a lower bound to quantitative easing, just as there is a lower bound for ordinary policy,” he said.

BOE policy maker Michael Saunders voiced a similar concern recently when he said that, in the U.K., “further asset purchases by themselves may be less effective in providing additional stimulus” without an interest-rate cut. The BOE’s benchmark interest rate is currently 0.1% and policy makers are mulling whether to take that below zero.

Unsurprisingly, central banks’ own research departments have typically argued for QE’s previous effectiveness, work that provides the backdrop to today’s policy debates.

Heyday Over

Recent Fed research claims QE helped prevent a slump in investment spending this year, preserving productive capacity for the rebound. Justifications for the ECB’s continued use of the tool are aided by calculations made last year that its QE program since 2015 contributed 0.3 percentage point each year to economic growth in the three years to 2018.

Yet even within the central bank community, the recognition is growing that the heyday of QE as a cure-all policy tool is probably over.

A paper by ECB researchers Peter Karadi and Anton Nakov in October warned that QE can be less effective in offsetting economic shocks like the pandemic that don’t emanate from the financial system.

With such doubts circulating, the lifespan of QE risks being extended artificially by the gap between how central banks see the effectiveness of QE and how the outside world does.

To Daniela Gabor, professor in economics at the University of the West of England, Bristol, the dominance of central bank stimulus in the last decade is a large part of why it’s becoming ineffective.

“To me, QE has become a cop-out,” she said. “It’s a way of introducing incremental changes in the monetary toolbox without really transforming how central banks and treasuries approach coordinating responses to economic challenges.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.