Central Banks Lagging Fed Show 2008-Style Coordination Missing

Central Banks Lagging Fed Show 2008-Style Coordination Missing

(Bloomberg) --

Almost a week since the world’s top financial officials pledged to use “all appropriate policy tools” to protect their economies from the coronavirus outbreak, markets are slumping and investors are wondering where the central banks are.

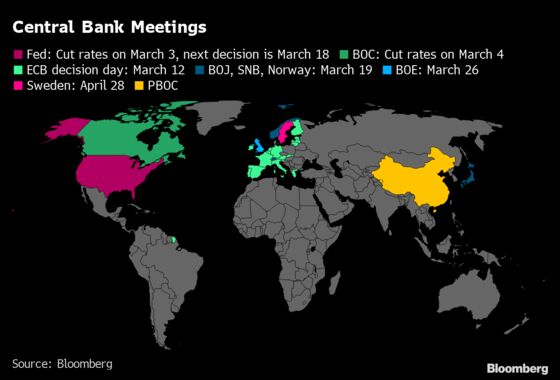

While the U.S. Federal Reserve and the Bank of Canada slashed their key interest rates almost immediately after the Group of Seven teleconference last Tuesday, their peers are moving much more slowly. None of the major European institutions have cut rates, nor has the Bank of Japan. Chinese measures have been limited.

It’s a far cry from the 2008 financial crisis, when six of the world’s major central banks cut rates in a coordinated move, and the Bank of Japan issued a statement saying it supported the action.

Some policy makers may be hoping governments can take the strain with fiscal stimulus. Interest rates are far lower than they were in 2008, and radical measures such as asset purchases and cheap long-term loans have stretched central banks almost to their limits.

“The Fed’s emergency cut last week didn’t do what it was supposed to do, which is provide a clear support to markets,” Karen Ward, chief market strategist for EMEA at JPMorgan Asset Management, told Bloomberg Television. “I think if it was coordinated, perhaps so, but it’s very hard to coordinate across central banks when we’re at the limits of ammunition.”

Yet with an oil crash adding to the sense of emergency, the pressure is mounting for monetary authorities to prove they haven’t totally exhausted their powers.

Euro-Zone Limits

The ECB holds a scheduled policy meeting on Thursday, and officials have so far shown no sign they intend to act before then. Even when they do, the measures might not be dramatic. Investors expect a 10 basis point rate cut, and some economists predict bond purchases will be boosted. A measure to direct liquidity to struggling small firms looks likely.

The dilemma is that the deposit rate is at record-low minus 0.5% and quantitative easing, which was resumed last year, is nearing limits intended to prevent the program breaching European Union law. Under President Christine Lagarde, officials have expressed concerns that their ultra-loose policies will damage the banking system and cause asset bubbles.

Any action will limit future options even further, meaning a common refrain from officials is likely to grow louder: governments must do more. So far though, only Italy has announced significant fiscal measures. Germany, the region’s largest economy and the one with the most public cash to spare, agreed on limited steps after more than seven hours of talks late Sunday.

Swiss Haven

The franc’s exchange rate plays an outsize role in the Swiss National Bank’s policy calculus, so officials are likely to wait for what’s announced by the ECB. A package of targeted loans wouldn’t exert as much pressure on the currency as a rate cut, lessening the pressure for the central bank to respond.

SNB President Thomas Jordan has said there’s room to reduce borrowing costs further, and the franc has surged to its strongest in five years against the euro. But banks already are up in arms about the minus 0.75% deposit rate, which means policy makers are probably reluctant to take any measures that’s aren’t absolutely necessary.

British Budgeting

The BOE’s next scheduled meeting is March 26, though it may not wait that long to act. The Treasury, led by a chancellor who’s been on the job less than a month, may deliver a package in the budget on March 11, and there’s a chance the BOE follows up with complementary measures.

Governor Mark Carney, whose term ends on March 15, has already said the bank has room to cut its benchmark rate near to zero -- it’s currently 0.75% -- and can take other steps as well. His successor, Andrew Bailey, has said fiscal policy or targeted loans to small businesses should be the focus.

Scandinavian Reversal

In northern Europe, central banks are under pressure to undo recent tightening. Sweden’s Riksbank -- where the deputy governor has been diagnosed with coronavirus -- ended half a decade of negative rates in December, and had voiced reluctance to go back below zero. Norges Bank was raising rates in the richest Nordic economy until September.

But this week’s market rout changed everything. Economists now expect oil-reliant Norway to cut its main rate by as much as half a point next week. The Riksbank says it’s ready to act, with a meeting set for next month. In Denmark, where policy makers use rates to keep the krone pegged to the euro, a March 12 cut following the ECB would leave its benchmark at minus 0.85%, the world’s lowest.

Japanese Buying

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda issued a statement aimed at calming markets and ensuring ample liquidity ahead of the G-7 call. He quickly followed up with reverse repo operations and a record-breaking purchase of exchange-traded funds, in moves that initially seemed to reassure investors.

The BOJ would rather avoid an expansion of a massive stimulus program that is close to its limits and is squeezing the banking sector through its negative interest rate. But a strengthening yen that hits corporate profits and the likelihood of solid wage increases and investment could change its view.

The government is also helping to ease the BOJ’s burden somewhat. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is expected to flesh out new emergency measures Tuesday, having unveiled interest-free loans for small businesses at the weekend.

Chinese Hopes

The People’s Bank of China has trimmed market borrowing costs while regulators have eased some rules on lending to small businesses, but policy makers have held off on broad cuts to interest rates or large-scale cash injections.

That’s partly due to China’s overall stance on stimulus being in a wait-and-see mode given the nascent improvement in containing the spread of the virus and previous expectations of a rapid recovery. But the nation’s heavy debt load and concerns over financial stability remain powerful incentives not to embark on a credit-fueled stimulus drive.

--With assistance from Francine Lacqua, Tasneem Hanfi Brögger, Carolynn Look, Brian Swint, Jeffrey Black, Craig Stirling, Catherine Bosley, Paul Jackson and Zoe Schneeweiss.

To contact the reporter on this story: Paul Gordon in Frankfurt at pgordon6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alaa Shahine at asalha@bloomberg.net, Zoe Schneeweiss

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.