Central Banks Face New Balancing Act With Their Huge Asset Piles

Central bankers around the world are mulling the future of their massive bond-buying programs in a post-pandemic world.

(Bloomberg Markets) -- Central bankers around the world are mulling the future of their massive bond-buying programs in a post-pandemic world, knowing that with big balance sheets come big expectations.

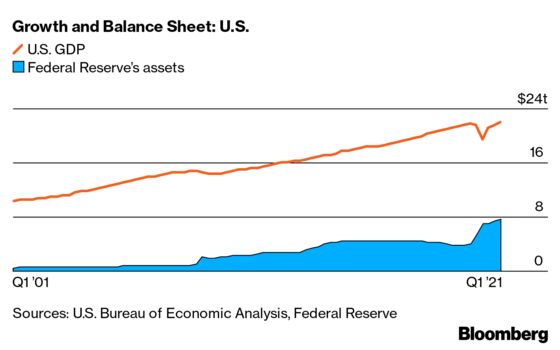

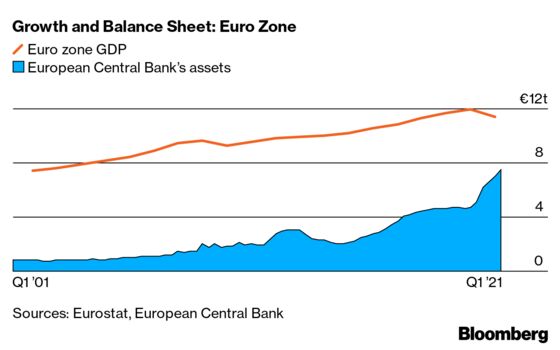

The Group of Seven developed economies piled on about $7 trillion in debt last year as they spent heavily to fight the pandemic and prop up their economies. Central banks ended up owning much of that new debt, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Even as asset purchases continue, with hundreds of billions of dollars spent each month, officials at the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank are among those figuring out how—or if—they can reduce asset piles that have been a mainstay of financial markets for more than a decade.

The problem is that markets have come to expect central banks to use their buying power to smooth over any hint of trouble. Governments may be tempted to lean on monetary authorities to use it to keep borrowing costs low indefinitely. And activists now also call on monetary officials to use their firepower to fight inequality and even climate change. Those disparate expectations add to the unease fueled by economists who for years have warned about the long-term effects of quantitative easing.

“The Fed balance sheet is going to be gigantic for a long time,” says Alan Blinder, a former Fed vice chairman who’s now a Princeton professor. “That worries some people,” he says—but not Blinder himself.

The size of the Fed balance sheet in coming years will largely be determined by Federal Open Market Committee decisions regarding asset purchases and reinvestment policies, the New York Federal Reserve Bank noted in a late May report. Yet the report projects that the balance sheet could rise by 2023 to $9 trillion, equivalent to 39% of gross domestic product. Under a range of scenarios, Fed assets could remain at that level through 2030 or drop as low as $6.6 trillion.

QUANTITATIVE-EASING TOOLS have been a welcome boon to monetary institutions faced with policy rates already near or below zero. But they’ve also magnified the political profile of central banks, leaving them more exposed to entanglement in fiscal policy—or the perception that they could be.

So-called fiscal dominance—in which central banks are prevented from acting on their inflation mandates for fear of harming the government’s finances—is the issue. It’s associated with a spectrum of concerns, ranging from the erosion of independence, with the possibility of monetary officials keeping policy too loose and unleashing inflation, to a regime change in which government borrowing is monetized, with central banks buying debt directly or agreeing to buy a certain amount.

How far the situation has come is starkly visible in Europe. Where once the mere purchase of debt of euro-area nations on secondary markets unleashed accusations of illegal monetary financing, high-ranking politicians in Italy and France have in recent months called for the bonds on the European Central Bank’s balance sheet to be canceled or turned into “perpetual” bonds that never get paid back.

The idea that government debt has to be honored is coming under attack. “We’re headed toward this sort of Modern Monetary Theory regime where the debt and free money supposedly have no consequences,” says Charles Plosser, a former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, who’s now a fellow at the Hoover Institution. “What I worry about ultimately is the politicization of the central bank.”

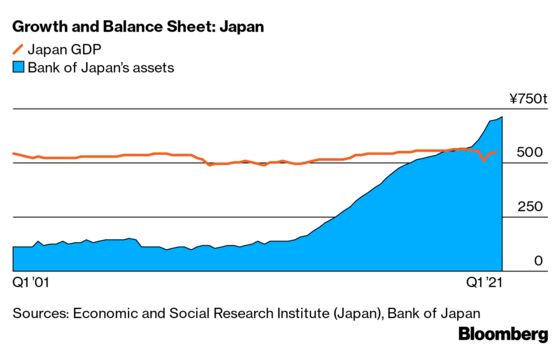

The concern is about a specific set of circumstances: With such a large balance sheet, a central bank such as the Bank of Japan, the Fed, or the ECB is the government’s buyer-in-chief. Indirectly, the monetary authority controls the government’s cost of borrowing. The current debates about so-called yield-curve control—buying that targets a specific yield at a given tenor—only underline this fact.

But if inflation comes along, the central bank governor is in a pickle. Raise rates, and the government screams. Keep them low, and you prove that your independence—and credibility to fight inflation—has gone.

The straightforward way to get out of this dilemma is to reduce the size of debt holdings as quickly as possible. Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey hinted last year that he may favor aggressive shrinkage also because it could create more room to maneuver in a future emergency.

But in 2013, after the U.S. had come out of the crisis sparked by the subprime meltdown, the Fed signaled an attempt to “taper” its own balance sheet, leading to an immediate spike in bond yields and global market turmoil. Central bankers are wary of doing the same again. Fed officials say there’s no need to discuss a change in the pace of bond-buying until much more progress has been made on their employment and inflation goals. Investors are laser-focused on when that moment might come.

The lesson from the Bank of Japan, which has advanced further in the direction of fiscal dominance than its peers, seems to be that any attempt to wind down the debt holdings of today could take a generation or more. “The BOJ will have to do it very, very slowly, hoping no one will notice that’s what it is doing,” says Richard Koo, chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute in Tokyo and a former adviser to Japanese prime ministers. “If they do it very carefully over, say, 20 to 30 years, they may be able to bring the balance sheet back to something normal.”

Quantitative easing has been part of the monetary toolkit for so long now that the definition of “normal” has changed. Where once the Fed maintained a “lean” balance sheet just greater than the value of bank notes issued, there’s little chance of a return to that. There are various reasons why central bankers will want to retain at least some of their current holdings indefinitely, from preserving their ability to intervene to smooth market functioning to helping the conduct of monetary policy.

To do so, central bankers may need to prove that they’re not captured by their finance ministries and that, when inflation returns, they can react. Vitor Constancio, ECB vice president until 2018, argues the fears about fiscal dominance are “wishful thinking” by market investors, a narrative that pressures the central bank to keep policy loose indefinitely.

“When inflation normalizes in a consistent way, central banks will start reducing the size of their balance sheets,” Constancio says. “I have no doubt about that.”

Black is an editor for Europe finance at Bloomberg News in Zurich.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.