Central Banks Dust Off Old Tools to Stem Risks From Easy Money

The tools have a long history in Latin America, helping the likes of Brazil and Mexico stabilize credit flows.

(Bloomberg) --

As global central banks swing back into easing mode, old tools long frowned upon by monetary purists are being embraced to ensure cash goes where it’s needed.

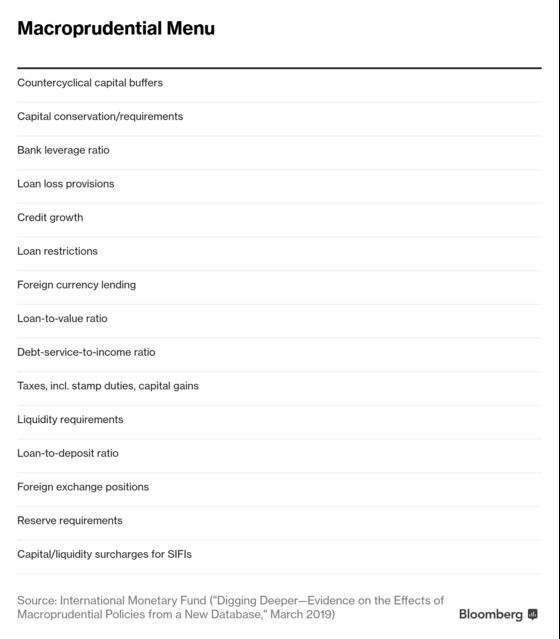

Having proven their stripes in emerging economies, macroprudential tools such as tweaks to bank reserve requirements and loan-to-value ratios for home buyers are gaining street cred. The screws can be tightened to avoid excessive borrowing and bubbly asset prices in an era of cheap money, and loosened in place of interest-rate reductions to save precious monetary firepower.

The tools have a long history in Latin America, helping the likes of Brazil and Mexico stabilize credit flows. And they’re increasingly in use across Asia: lending curbs have kept a lid on Singapore’s once runaway apartment prices, while reductions to bank reserve requirements have been used to complement interest-rate cuts in Indonesia.

At a time when borrowing costs are heading south again, there are now louder calls for developed-market central banks to follow suit. With many governments, businesses and households already swimming in debt and bond, stock and property markets richly valued, macroprudential tools can help steer fresh credit where it’s needed and deter money from flowing to where it’s not.

Macroprudential tools are set to increasingly come into play “to make sure the liquidity is going to the right places,” said Deyi Tan, Hong Kong-based Asia economist at Morgan Stanley. “You need to defend growth” while “some economies will have a leverage problem that’s still not being addressed.”

Among macroprudential policies’ ardent defenders is the chief of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. At a June 21 macroprudential policy conference in Germany, Eric Rosengren bemoaned that Japan’s banking crisis in the late 1990s, among other downturns, could have been mitigated with the use of such lending controls.

“The extent of the problems revealed by the Japanese banking crisis should have been sufficient to lead many countries to enhance their suite of macroprudential tools,” he said. “Unfortunately, it took an even bigger and more global problem -- the financial crisis that began in 2008 -- before countries turned to the job of improving macroprudential policies.”

Fed chief Jerome Powell has counted macroprudential tools as among the “principal” levers to manage financial stability, ranking them above interest-rate tweaks in that regard in a March press conference. The European Central Bank now publishes a biannual “Macroprudential Bulletin” canvassing the latest research and practice on the measures, with the most recent newsletter featuring analysis that the global system is far more resilient than before the last crisis because of them.

Broadly, it’s a tone of cautious enthusiasm for the tools. Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda has suggested that because the prolonged interest-rate environment has created unique problems, the jury is still out on what’s the best mix of monetary and macroprudential policies to achieve price and financial stability. The Bank of England’s Donald Kohn, too, has noted that macroprudential tools are still relatively untested in a real downturn.

The IMF, Bank for International Settlements, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Kristin Forbes have added support for macroprudential tools in fresh research this year on their effectiveness. In June, the BIS built on prior research in its review that macroprudential policies can make central bankers’ jobs a bit easier.

“The experience of the past two decades indicates that macroprudential measures do help improve the trade-offs monetary policy faces,” according to the BIS annual report. At the same time, the BIS warned that macroprudential tools cannot alone contain the buildup of financial imbalances, and that political economy pressures might impede their use.

Monetary purists would argue that setting the correct interest rate will lead to the optimal level of credit expansion and economic activity. Macroprudential tools can impede that process, and even distort asset prices as canny individuals will always find a way around the rulebook, they argue.

Indeed, MIT’s Forbes noted in a paper this year that it’s difficult to pass judgment on macroprudential policies if success means a crisis that never happened and because their use has increased significantly in the past few years without being tested in a downturn.

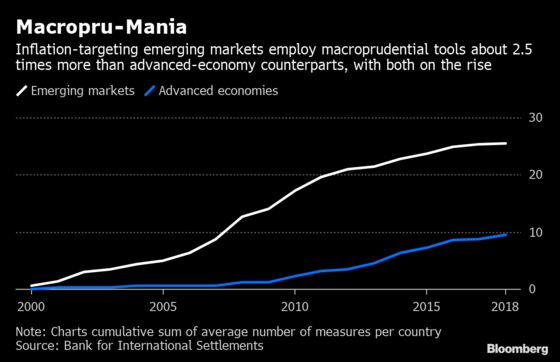

So far, emerging-market economies have gone macroprudential at a far higher rate than developed markets. Latin America has proven a good “laboratory” for the tools, given their persistent use there, the BIS argued in a 2017 paper. Brazil’s work in adjusting reserve requirements to control credit growth was among the successes cited.

There, too, macroprudential tools have not finished the job: Argentina imposed capital control measures Sept. 2 in order to rescue foreign currency reserves and the peso. Such emergency policies are exactly what macroprudential tools are meant to render less necessary.

Central banks in Asia also have promoted the merits of the targeted tools, occasionally pairing their implementation with decisions to hold interest rates. Tempted to raise the benchmark interest rate in September 2018, the Bank of Thailand instead made a bid to reduce property-bubble risk by raising loan-to-value ratio limits, buying time until a hike in December.

Since April, when those measures took effect, the global policy trend has turned dovish. Thai central bankers might lean again on macroprudential policies soon, even after a surprise rate cut in early August. Minutes of their June meeting showed a growing concern around lending for vehicles, and policy makers already are weighing how to contain a soaring currency against global pressures for lower interest rates.

On the easing side, Bank Indonesia has employed macroprudential measures to encourage lending, including reducing the reserve ratio for banks. The reserve-ratio cut complements other “accommodative,” non-monetary measures to accelerate growth, said Juda Agung, the central bank’s executive director for macroprudential policy.

While EM central banks have had to make “more challenging monetary policy trade-offs and impossible trilemmas than their DM counterparts,” the latter might also find the necessity of macroprudential tools in the next global downturn, Nomura Holdings Inc.’s Rob Subbaraman, head of global macro research, and rate strategist Andrew Ticehurst said in a July research note.

“Central banks have unwittingly contributed to an unsustainable debt-fueled economic growth model,” they wrote. “Overburdened” monetary policies should be “complemented by equipping major central banks with a larger toolkit, including more active use of macroprudential tools and FX intervention.”

--With assistance from Suttinee Yuvejwattana.

To contact the reporter on this story: Michelle Jamrisko in Singapore at mjamrisko@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Malcolm Scott at mscott23@bloomberg.net, ;Nasreen Seria at nseria@bloomberg.net, Michelle Jamrisko

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.