Central Bankers Plot Course Through End of Easy Money Minefield

Central Bankers Plot Course Through End of Easy Money Minefield

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

Global central bankers are turning toward tighter monetary policy, yet still indicating they will take longer and follow different paths than investors currently expect.

Just this week:

- The Federal Reserve confirmed it would start slowing its asset purchase program, but Chair Jerome Powell said he won’t consider hiking interest rates until the labor market heels further.

- The Reserve Bank of Australia dropped a pledge to anchor short-term bond yields and signaled it has no plans to raise its benchmark rate anytime soon.

- The Bank of England defied market expectations by not raising rates, while sticking with the view they will still need to rise in “coming months.”

- At the more hawkish end of the spectrum, Poland and the Czech Republic tightened rates, and Norway indicated it will do so again in December.

With inflation strengthening and growth slowing, most policy makers in developed economies face a balancing act in which the risks are almost equally shared between acting too fast or too slow. That increases the chances of surprising markets and committing a policy error.

Global bonds rallied this week as the rate-hike bets that spurred an epic sell-off in October collapsed. U.S. 10-year yields dropped 8 basis points to 1.53% on Thursday, the biggest decline since August, while Australia’s three-year yield has seen the biggest drop in a decade, unwinding part of last week’s spike that was the steepest since 2001.

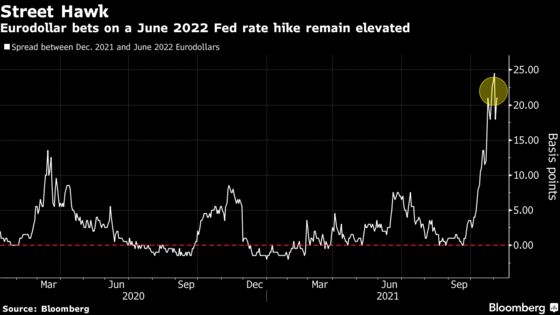

The upshot is officials will likely tread carefully and at varying speeds, despite investors pressing for a quicker end to easy money with wagers the BOE will hike in February, the Fed in June and even that the European Central Bank will reverse its dovish stance at some point in 2022.

“We are entering perhaps the most interesting phase for global monetary policy in living memory, that is, if you are under 50 or so,” according to Chris Marsh, a senior adviser at Exante Data LLC.

While those who witnessed the 2008 financial crisis and last year’s pandemic fallout may disagree with that view, JPMorgan Chase & Co. economists estimate that by the end of the year, about half of the 31 central banks they track will have lifted their benchmarks from last year’s lows.

Driving most of the shifts is inflation proving broader and more stubborn than was once expected as post-lockdown demand, frayed supply chains, tightening labor markets and surging commodity costs propel prices higher and potentially for longer.

Whether those forces fade, as most central bankers still expect, will ultimately determine what happens next.

Every policy maker will want to avoid the ECB’s famous errors of 2008 and 2011 when rates were boosted only for the inflation threat to evaporate and growth to be squeezed.

Some, including the Fed, will also want to road-test new strategies for allowing inflation to run hotter than historically so as to cement recoveries in growth and hiring.

Powell, who isn’t sure he’ll even have a job himself in February, said Wednesday “the inflation that we’re seeing is really not due to a tight labor market.”

The opposing risk is if central banks wait too long and inflation doesn’t ease, expectations for it among companies and consumers could become embedded, creating a price spiral that’s harder to rein in and which threatens to roil markets.

Some emerging markets, including Brazil and Russia, are already aggressively tightening policy in the face of accelerating prices. Norway, South Korea and New Zealand have also begun to edge rates higher.

The betting of economists is that most central bankers will move with caution. JPMorgan Chase predicts global policy rates will end next year around three quarters of a percentage point below their 2019 average.

“Central banks are splitting on inflation risks,” said Mansoor Mohi-uddin, chief economist at the Bank of Singapore Ltd. “Thus we think bond markets have already priced in too much hiking in 2022.”

At Nomura Holdings Inc., economists led by Rob Subbaraman also say hikes will be more limited than in previous cycles because the pandemic has left scars which will restrain the rate economies can grow before they ignite inflation.

They forecast average global growth will be around 2.5% in the next decade, down from 2.8% in the post-financial crisis years and 3.4% pre-2008.

“Central banks will not need to raise rates aggressively to tighten financial conditions to keep inflation in check or ease pressures in the economy,” the Nomura economists said in a report. “The so-called terminal rate will likely be lower than in previous cycles.”

Krishna Guha, head of central bank strategy at Evercore ISI, is not so sure. He suggests the Fed will stay on hold until December 2022, but then move a “bit faster, bit further.”

| Read More... |

|---|

Even as some tighten, economists at Berenberg Bank, predict “unsynchronized monetary policy normalization” given that central banks tend to hike at their own pace even if they ease simultaneously when shocks like Covid-19 hit.

Already, ECB President Christine Lagarde is pushing back against market bets for rate increases in 2022, saying this week that conditions for them “are very unlikely to be satisfied next year.”

That echoed RBA Governor Philip Lowe, who said he is in a “struggle with the scenario that rates would need to be raised next year.”

Japan’s new government and central bank this week confirmed they will keep cooperating to achieve 2% inflation, a strategy that will temper market speculation of any early stimulus exit there.

Even BOE Governor Andrew Bailey told Bloomberg that rate pricing is currently a “bit overdone.”

Minds can change quickly though. The Fed tapered sooner than onlookers were thinking earlier this year. As recently as late September, Bailey was saying the U.K. economy faced “hard yards.”

“It is going to be very challenging for the Bank of England, as well as other major central banks, to engineer a smooth transition from the extraordinary monetary policies we have seen over the pandemic period,” said Katharine Neiss, chief European economist at PGIM Fixed Income.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.