Cash Sent to Latin American Families Defies Forecasts for Plunge

Cash Sent to Latin American Families Defies Forecasts for Plunge

(Bloomberg) -- The World Bank’s prediction in April was dire: Cash transfers from immigrants in the U.S. to family in Latin America would plummet 19% this year due to the pandemic.

Now, with remittances surging, the lender says such payments are on track to be roughly equal to last year’s total.

It turns out that forecasters likely underestimated immigrants’ incomes, which were sustained by U.S. government relief payments and an ongoing economic rebound that was good enough to recover millions of jobs. Transfers also probably have been boosted by immigrants’ desire to send money to relatives in a region facing more dire economic and health circumstances than the U.S.

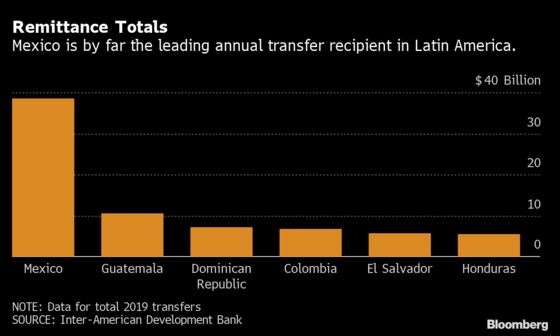

The unexpected flow of payments has amounted to what Mexico’s president this month called a “social miracle” helping millions of families cover basics like food and medicine while the country refrains from providing aid to individuals to avoid hurting its finances. Remittances to Mexico rose 14% from a year earlier in October and are heading for a record $40 billion this year, equal to about a month of total exports by the country.

“Migrants in the U.S. aren’t suffering as much as migrants in other host countries,” said Dilip Ratha, the lead economist for migration and remittances at the World Bank. “That’s been a factor in the resilience of remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean.”

The U.S. job market remains shaky despite improving from the depths of spring lockdowns that had a significant impact on businesses like restaurants, hotels and childcare where new immigrants often work. Yet the unemployment rate for foreign-born workers fell in November to 6.7% -- close to the 6.3% native-born rate and well below the 16.5% peak in April, when it was almost 2 percentage points higher than the national rate.

“When we saw the figure of the unemployment rate in the U.S. jumping that much, we didn’t think at that point the recovery would be so fast,” said Marta Ruiz-Arranz, a principal economic adviser at the Inter-American Development Bank in Washington. “As soon as the U.S. economy reopened, we saw a big bounce back of remittances.”

Beyond that, about half of foreign-born U.S. citizens and permanent residents from Mexico, Central America and the Dominican Republic likely had access to stimulus checks and jobless benefits, according to Federal Reserve Bank of New York research.

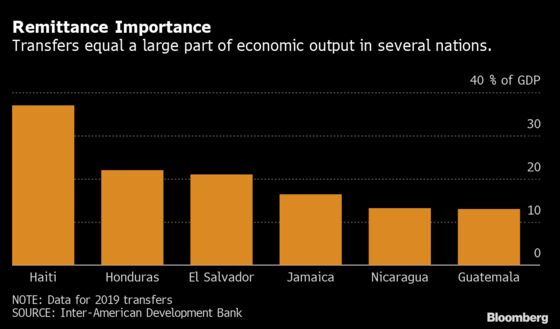

In El Salvador, where remittances equal one-fifth of economic output, November transfers climbed 12% from a year earlier after a 40% drop in April. Transfers to Guatemala are up 20% after a similar rebound.

One beneficiary of the U.S. rebound is Guillermo Castillo, who in March lost his job at a Victoria’s Secret warehouse in Ohio and temporarily halted remittances to his father and girlfriend in his native Guatemala. By June he’d landed another warehouse position that paid an $8 per hour Covid-19 incentive on top of his $17 hourly wage, he said, and by July he’d resumed the same payments as before.

“It was a relief because my parents depend on my remittances,” Castillo said, adding that the new work let him continue volunteering at food banks. “We’re all trying to live life as normal as possible, using masks and protecting ourselves while we work.”

Hardships at home likely spur immigrants to send more money to Latin America, said Manuel Orozco, director of the Center for Migration and Economic Stabilization at Creative Associates International, a Washington-based development company.

Orozco said some immigrants in March and April probably faced temporary hurdles from closures of Western Union and MoneyGram locations, with transfers rebounding when they reopened. His research found many immigrants were generally better prepared this year for an economic shock than 2009, when remittances to Mexico tumbled 15%.

Mexico likely avoided a repeat in part because its immigrants in the U.S. largely came in earlier decades than those from Central America and were more established before the pandemic, the IDB’s Ruiz-Arranz said. That meant more had legal status and access to stimulus payments and unemployment benefits often topping prior pay.

While the stability in remittances contrasts with steep drops seen elsewhere around the globe, other destinations have also defied pessimistic projections. Ratha said Pakistan and Bangladesh saw inbound transfers rise as Saudi Arabia’s cancellation of the Hajj, the annual Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, let migrants who would have spent savings on travel instead send money home.

The World Bank still expects remittances to Latin America to suffer eventually, with an 8.1% slump expected for next year. The New York Fed also warns immigrants probably respond to unemployment with a lag, drawing on savings to continue remittances. That imperils the longer-term outlook for payments as the jobless rate remains elevated.

However, Ruiz-Arranz of IDB said Central America’s recent hurricanes make it more compelling for immigrants to send money amid suffering and devastation back home. She said inbound remittances may dip in 2021 from this year, “but they will continue to remain high.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.