Canada Says, ‘Give Me Your MBAs, Your Entrepreneurs’

Foreign talent helps power the nation’s economic boom.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- Ayesha Chokhani, who grew up in Kolkata, has no love of the cold. Yet when she went to study for her master’s degree, the 29-year-old student chose the University of Toronto, where winter temperatures can fall well below freezing.

Chokhani had her pick of elite schools. She turned down Cornell and Duke in the U.S. Her reasons were clear: The anti-immigrant rhetoric from the Trump administration made her nervous. And Canada had an additional draw: She can stay up to three years after she graduates and doesn’t need a job offer to apply for a work permit. “I wanted to be sure that wherever I go to study, I have the opportunity to stay and work for a bit,” she says.

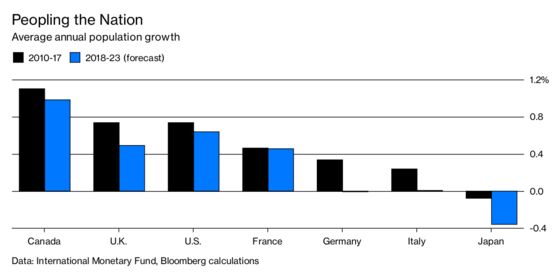

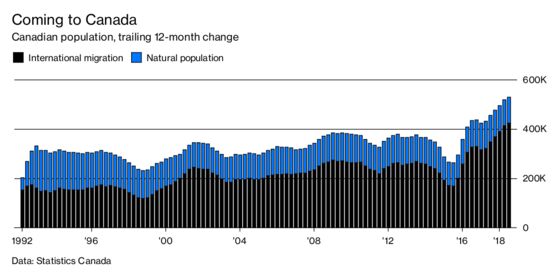

In August, there were about 570,000 international students in Canada, a 60 percent jump from three years ago. That surge is helping power the biggest increase in international immigration in more than a century. The country took in 425,000 people in the 12 months through September, boosting population growth to a three-decade high of 1.4 percent, the fastest pace in the Group of Seven club of industrialized nations.

Canada’s immigration system has long targeted the highly skilled. More than 65 percent of foreign-born adults had a post-secondary degree in 2017, the highest share tracked by members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “We are the biggest talent poachers in the OECD,” says Stéfane Marion, chief economist of the National Bank of Canada. As a result, he says, the country is better equipped to deal with globalization and technological change—“it’s a massive, massive advantage.”

Amazon.com Inc. has created 10,000 jobs in Canada in the past few years and has plans to add more than 6,000. “We’re continuously impressed by the caliber of talent, and that includes folks who have come here from all over the world to build a new life,” says Tamir Bar-Haim, Amazon’s head of advertising in Canada, who immigrated from Israel.

Hassan Bhatti embodies Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s strategy of promoting immigration to bolster economic growth as the population ages. The 26-year-old Pakistan native co-founded a software startup called CryptoNumerics. His growing team of 10 works with other young companies in shared offices in the heart of Toronto’s booming tech scene.

Bhatti has an undergraduate degree in physics and economics from the University of British Columbia. He’d planned to apply to Stanford or Harvard business schools, but his visa was rejected around the time the Trump administration banned immigration from seven mostly Muslim countries. (International applications to U.S. business schools dropped about 11 percent in 2018, according to the Graduate Management Admission Council in Reston, Va.)

Bhatti decided to stay in Canada until his passport came through, and now he’s rethinking a move to America. “Before it was like, the U.S. is the biggest economy. You want to go there. It was much more singular,” he says. “My perspective changed.”

For all its benefits, the immigration surge is becoming a contentious political issue. In the past couple years, the province of Quebec, for example, has seen a big jump in asylum claims by people arrested while illegally crossing the border from the U.S. It’s now moving to cut its share of legal immigrants by 20 percent in 2019, to about 40,000. A new federal party, the People’s Party of Canada, is also pushing to reduce immigration.

The University of British Columbia at Vancouver will raise its target for foreign students to 30 percent by 2022, from a cap of 15 percent in 2014, a plan that some have criticized. “As public institutions, they have a responsibility to cater to the local Canadian population,” says Peter Wylie, a UBC associate professor of economics.

University leaders counter that, because international students pay higher tuition, they help institutions fulfill their public mission. Foreign engineering students, for example, pay $32,700 a year, while Canadians pay $4,500.

These students will be more of a benefit to Canada if they stay in the country and use their expertise to start companies. In 2017 only 9,410 former international students transitioned directly to permanent residency. That number increases to 44,000 when including those who have taken other routes such as getting a work permit first or going home before applying, data from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada show.

Chokhani isn’t sure she’ll remain in Canada. She’s found it tough to afford Toronto’s famously high rents—a byproduct of the country’s booming economy—while also paying about $78,000 for her MBA at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management. “I’m still open, of course, to liking the city more,” she says. “But I don’t know if it’s the smartest decision to live here after.” —With Sandrine Rastello

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jacqueline Thorpe at jthorpe23@bloomberg.net, John HechingerCristina Lindblad

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.