The Bond Market’s Hubris Is Getting Hard to Explain

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Yields on U.S. Treasuries, the global benchmark, haven fallen in recent days to their lowest levels since January 2018. Not only that: Yields on Treasuries with maturities out to 10 years are all below the Federal Reserve’s target rate for overnight loans between banks. What’s puzzling is that economists have been boosting their forecasts for growth this year. Recent history suggests it’s a good time to take some chips off the table, but instead, bond traders are doing the opposite.

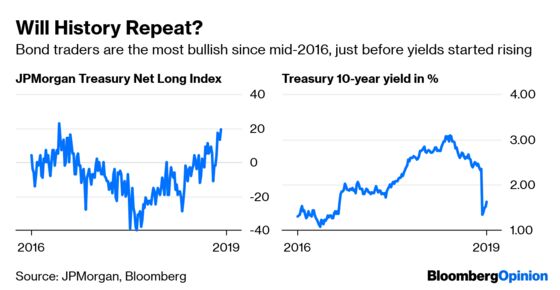

JPMorgan’s widely followed weekly survey of bond-market sentiment showed traders are their most bullish since mid-2016, which just happens to be when yields starting shooting up, generating losses for investors in the second half of that year. At a reading of 19, JPMorgan’s All Client Net Long index is well above the average of negative 3 since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. Given the bond market’s track record over many years in accurately forecasting the economy and inflation, it’s hard to doubt traders in this area. Even so, it’s hard to justify current yields if a recession isn’t imminent. A monthly survey by Bloomberg News conducted from May 3 to May 8 shows that economists have pushed back their timing for the start of the next recession to 2021 from 2020. Economists also boosted their forecast for economic growth this year, to 2.6% from the 2.4% estimated in April’s survey. Then consider that at 2.43% on Tuesday, yields on 10-year Treasuries are far below the 3.20% to 3.27% level that economists surveyed by Bloomberg News in December estimated they’d be by now.

It’s true that betting against the bond market in recent years has made many smart investors look dumb. And it’s not like there’s nothing to be worried about, with the U.S-China trade war taking a turn for the worse. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – which had already drastically downgraded its global economic projections in March – did so again on Tuesday, trimming its 2019 forecast to 3.2% from 3.3%. On top of that, Fed Chair Jerome Powell said on Monday that he agrees the torrid market in high-risk corporate loans looks a lot like the mortgage industry in the run-up to the subprime crisis.

LUXURY IS GETTING MARKED DOWN

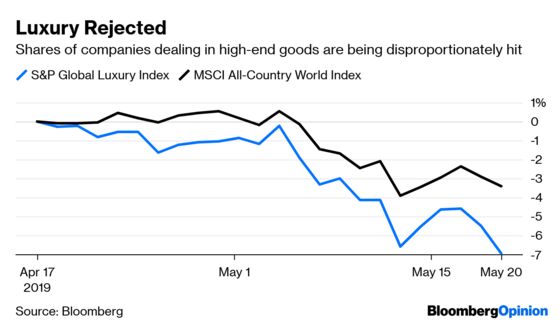

Judging by recent trends in the market for luxury goods, perhaps bond traders aren’t so crazy. De Beers’s diamond sales plunged to the lowest since 2017 in the company’s latest offering, underlining a slump in the industry worldwide. Sales by the Anglo American Plc unit dropped 25% from a year ago to $415 million, and were down 29% from an offering last month, according to Bloomberg News’s Thomas Biesheuvel. Sales are down even though the average price for a top-25 quality, 1 carat diamond with a clarity between internally flawless with no inclusions, or marks on the surface, to very slight inclusions is the lowest since at least 2005, according to the Rapaport Diamond Trade Index. It’s not just diamonds, though. The S&P Global Luxury Index of 78 high-end goods companies, which has been a consistent outperformer in recent years, has suddenly fallen out of favor. It’s down 6.18% the last month, versus a drop of just 2.79% for the MSCI All-Country World Index. Then there’s gold, which is trading near its lows of the year, which is odd for an asset that typically sees great demand in times of economic uncertainty. That raises the question of whether gold’s poor performance is due to a lack of demand, as consumers decide it’s no time for extravagant purchases.

THERE’S NO ‘REAL’ PROFIT GROWTH

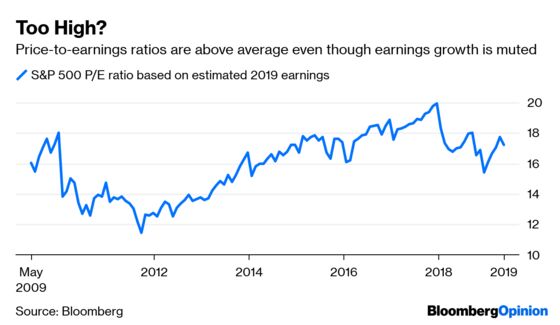

The S&P 500 Index rose as much as 1.01% on Monday in its biggest gain since April 1. The advance was generally credited to a decision by the U.S. to grant limited relief for consumers and carriers that do business with Huawei Technologies, a day after the White House’s moves against the Chinese telecom giant battered stocks. Whatever the reason, it’s unlikely tied to the prospects for earnings. Profits grew just 0.71% in the first quarter based on the 92% of the S&P 500 members that have reported first-quarter results, a rate of increase that doesn’t even beat the current low rates of inflation, according to Bianco Research. “This means there is no ‘real’ growth, so it would be difficult to describe (first quarter) results as great,” Jim Bianco, the firm’s president and founder, wrote in a research note Tuesday. It’s unlikely to get better anytime soon, with estimates calling for earnings growth of just 1.1% this quarter and 1.8% in the third quarter, before miraculously surging 8.1% in the final three months of the year. So, stocks might be able to avoid the earnings recession predicated by many at the start of the year, but there’s still a rising dollar to worry about. The Fed’s Trade Weighted Real Broad Dollar Index is back to about its highest level since 2003 and global trade volumes are the lowest since the financial crisis.

SHEKEL SAGA GRIPS CURRENCY MARKET

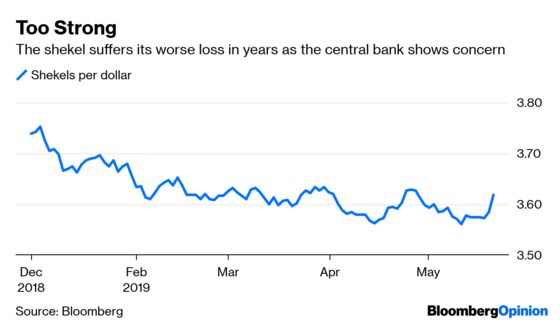

Israel’s shekel has been among the best currencies this year, right behind the top-performing Russian ruble. The good vibes came to a screeching halt Tuesday as the shekel fell about 1% in its biggest drop since June 2016. It turns out, the shekel’s gain was a case of too much of a good thing being bad. Traders abandoned the currency on Tuesday amid concern the Bank of Israel will intervene in the foreign-exchange market to halt its rise, according to Bloomberg News’s Ivan Levingston. The bank this week singled out the currency’s appreciation as the main factor keeping inflation below its 2% target despite the economy expanding at its fastest pace since 2016. Analysts heard a dovish tone – and saw a likelier chance the central bank will buy dollars for the first time since January to rein in the currency. Lifted by Israel’s export-driven economy and foreign direct investment, the shekel has held up well even after policy makers said in the minutes of their last meeting that they’ll consider buying foreign currency for the first time since January if the appreciation trend continues. Intervention generally doesn’t work for major currencies, but for less liquid ones like the shekel it can be an effective tool – as currency traders know well.

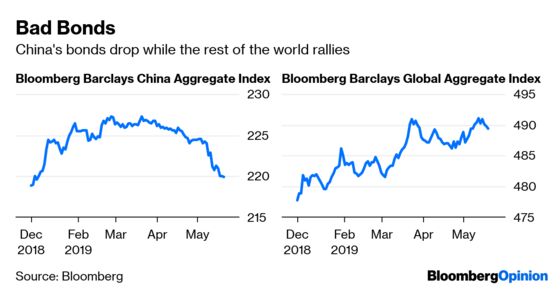

CHINA BONDS SUFFER

The escalating trade war between the U.S. and China has put a spotlight on the Asian nation’s currency. And while the yuan has depreciated this month, perhaps the real focus should be on China’s $13 trillion bond market. The Bloomberg Barclays China Aggregate Index is already down 2.03% this month, the most in the world and poised for its worst showing since June 2018. That follows a 1.01% slump in April. The declines are a bit jarring given that April 1 was the day that some of China’s onshore government and policy bank bonds were eligible to be included in the benchmark Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Total Return Index. After a phase-in period of 20 months, some 364 Chinese securities will ultimately account for 6.1% of the $55 trillion of debt covered by the index. This change was supposed to make it easier for global investors to access China’s bond market while improving liquidity. While that still might be the case, the recent action suggests capital may be fleeing China’s bonds. After all, nobody wants to own bonds in a depreciating currency. Citing ChinaBond data, Bloomberg News reports that monthly inflows have averaged 6.8 billion yuan ($984 million) this year, versus the 44.4 billion yuan seen in 2018. Global investors are concerned the yuan may weaken past 7 per dollar for the first time since the financial crisis (it was at 6.9211 on Tuesday). A breach of that level could cause capital to flee the country, resulting in financial instability and a deterioration in China’s balance of payments.

TEA LEAVES

The Fed’s Powell roiled markets after the central bank’s most recent monetary policy meeting on April 30 and May 1 by saying that the current low rates of inflation are likely “transitory” in nature. The comment suggested that just maybe the Fed didn’t agree with the market’s view that interest rates would need to be reduced this year. But Powell has shown he sometimes struggles with communication. Was this one of those times when what Powell said didn’t exactly jibe with the sentiment of his fellow policy makers? We may find out Wednesday when the Fed releases the minutes of that policy meeting, providing what Bloomberg Economics calls “greater clarity on the breadth of the perception among policy makers that the recent soft patch in both economic activity and inflation is transitory.” It will be worth watching for hints as to whether the “transitory” camp contains a few, several, or many members of the Federal Open Market Committee, according to Bloomberg Economics.

DON’T MISS

Traders Diverging From Economists Puts Fed in Bind: James Bianco

Time to Repeal Rule That Aided Uber’s IPO Flop: Stephen Gandel

Buying Pipelines Should Be Easier Than This: Liam Denning

Brazil’s Rich (Sort of) Tighten Their Gucci Belts: Mac Margolis

Indonesia Is Turning Chinese With This Debt Binge: Shuli Ren

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.