BOE Diverges From Fed on Communicating Interest-Rates Policy

The Bank of England’s dispute with financial markets about how to communicate monetary policy isn’t the first.

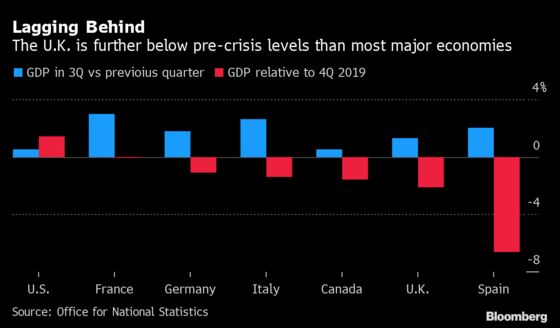

(Bloomberg) -- The Bank of England’s dispute with financial markets about how to communicate monetary policy isn’t the first. Until investors recognize how the U.K. central bank’s approach diverges from the guidance from the U.S. Federal Reserve, more are likely to come.

If there is one lesson to be taken from the backlash against the BOE’s surprise decision this month to leave interest rates unchanged, it’s that language can be as powerful as policy.

No change came as a shock after Governor Andrew Bailey warned in October that policy makers would “have to act” to curb inflation. Investors had priced in the first increase in borrowing costs since the start of the pandemic, prompting a surge in borrowing costs in financial markets. Mortgage lenders responded by withdrawing cheap mortgage deals. Bailey’s words had the effect of delivering a near-full 0.15% rate hike.

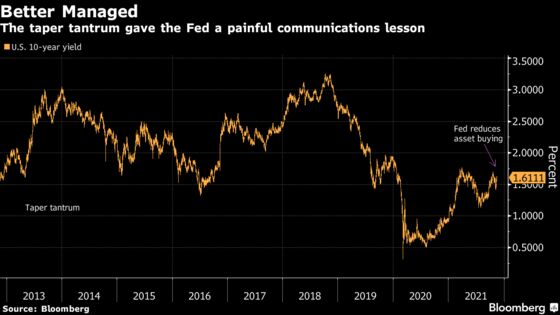

The turmoil in U.K. markets stands in contrast to the system the Fed has adopted since 2013, when a few misplaced words prompted a widespread sell-off in U.S. Treasury securities and emerging-market assets.

Bailey on Monday blamed U.K. market participants for the misunderstanding. He said saying investors took his “conditional” statements on the direction of interest rates at a G-30 conference on Oct. 17 and turned them into “unconditional views of the world.” Hours after the rate decision on Nov. 4, the governor told Bloomberg TV it’s not his job to “steer markets.”

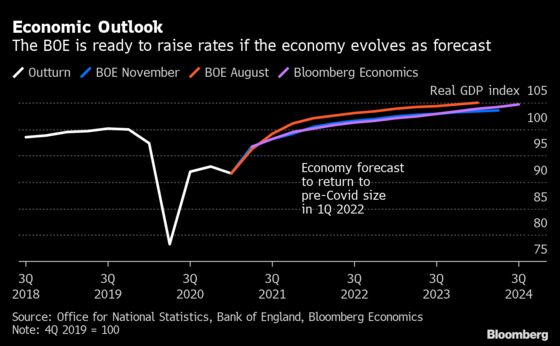

His distinction is important as investors and many economists have already moved to price in a rate increase on Dec. 16 despite the surprise this month.

The Fed has aimed for more detailed guidance and steady markets since the “taper tantrum” eight years ago. In that episode, the then-Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke told Congress that asset purchases would slow at a future date. Investors reacted violently.

Between May and December 2013, the 10-year yield rose to 3% from 2%, prompting dollar investors to pull money in developing nations back home. The incident destabilized global markets.

This year, the Fed carefully prepared investors for a shift in policy, and by the time the Fed announced a cut in its monthly asset purchases, it was well expected. Treasury yields held steady.

Bailey’s stance is that policymakers will comment on economic conditions and leave it to markets to interpret those remarks. It’s a form of “caveat emptor” -- buyer beware. If investors get it wrong, they bear the losses.

“We discuss our views on the outlook to try to ensure broader points get through,” BOE policy maker Michael Saunders told members of Parliament at a hearing with Bailey on Monday. “It is not possible to remove all uncertainty.”

Philip Shaw, U.K. economist at Investec, says the Fed’s careful guidance, in contrast to what some have called the BOE’s constructive ambiguity, was “not philosophical but practical,” having learned its lesson eight years ago.

“It seemed as though they were mismanaging things [back then]. Because of that, the Fed takes every opportunity to ... be granular about guidance to avoid markets getting a jolt.”

Underscoring the importance of communication, the Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis said in a blog in August: “One explanation for this difference in market responses is that the announcement in 2021 was in line with market expectations and the announcement in 2013 came earlier than expected.”

The consequences of BOE decisions are not as significant as the all-powerful Fed, and Shaw accepts that “it is not the bank’s job to spoon-feed markets.”

“But if it thinks it has been misinterpreted, it is the bank’s job to say that,” Shaw said. “It is not the bank’s job to mislead markets.”

The BOE has a checkered communications history. When Mark Carney was governor and delivered guidance that didn’t match the bank’s action, he was dubbed an “unreliable boyfriend.” The same label has now been attached to Bailey.

In summer 2017, the problem was so acute that markets had stopped listening to the BOE’s signals. In the minutes to the September rate meeting that year, the BOE inserted guidance that rates were likely to rise “in the coming months”, an unusually strong turn of phrase to alert markets that an increase was imminent.

In the last few months, BOE officials have been reminding market participants of that 2017 period, according to U.K. economists. Bailey himself said his G-30 comments were made because markets were not listening and he felt he needed to re-emphasize “the primacy of the inflation target.”

His explanation sums up the muddle the BOE is in. Because it will steer markets when it wants, markets will expect to be steered. “You can’t have your cake and eat it,” Shaw said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.