Big-Data Infusion for U.S. Inflation Gauge Starts With Apparel

Big-Data Infusion for U.S. Inflation Gauge Starts With Apparel

(Bloomberg) -- Go inside the global economy with Stephanie Flanders in her new podcast, Stephanomics. Subscribe via Pocket Cast or iTunes.

The U.S. consumer price index, which traces its origins back more than a century, gets an infusion of big data this week to bring the Labor Department closer to what it sees as the future for economic indicators.

After two years of study, more than 1,000 price quotations gathered from staff surveys of an unidentified department-store operator will be replaced with data fed directly from the company, labeled “CorpX” by Bureau of Labor Statistics economists. The prices will mainly be for apparel but not limited to that sector.

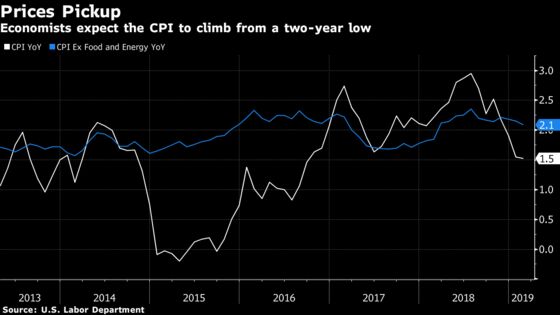

The switch takes effect Wednesday with the release of March CPI at 8:30 a.m. in Washington. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg project it will show a pickup to a 0.4 percent monthly gain as well as an acceleration on an annualized basis to a 1.8 percent rate amid rising gasoline costs -- up from a two-year low of 1.5 percent in February.

Excluding food and energy, the annual core CPI increase was probably unchanged at 2.1 percent -- likely keeping the Federal Reserve’s preferred core gauge just below the 2 percent rate the central bank targets for overall inflation.

The data changes are more evolution than revolution, but they’re a big step toward how statistical agencies will gather numbers in the future as they seek a more accurate and timely read on the economy that’s also less expensive to produce. The “CorpX” data will be a complete tally, not just a limited survey or sampling, that the BLS hopes will pave the way for directly acquiring other corporate data sets, says Crystal Konny, chief of the BLS unit for the CPI.

“Getting it and using it this way is a major change in the way the data is delivered to us, but not necessarily a major methodological change because we’re still calculating the index much the same way, as close as we can to the current CPI,” Konny said in an interview.

Other agencies are supplementing their reports and analysis with private data, including the Census Bureau and Fed. But one potential pitfall is that companies provide data voluntarily, so they can stop at any time, Konny says. BLS staff also experienced a setback along the way when “CorpX” made a change to their database.

The BLS change may add volatility in clothing prices, but the impact on the main index will be relatively small, subtracting maybe 0.1 percentage point from the annual CPI rate, according to Michelle Girard, chief U.S. economist for NatWest Markets Securities Inc. and the most accurate CPI forecaster in Bloomberg’s latest ranking.

Flash Sale

“While, theoretically, this shift should not introduce a downward or upward bias in the data, we believe that prices captured using actual transactions data are more likely to be biased lower,” Girard wrote in a report. “Transactions data could capture lower price points from a flash sale that a data collector may not have observed.”

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economist Spencer Hill estimates the change could reduce core inflation in March by around 0.05 percentage point from the monthly change. Omair Sharif, senior U.S. economist at Societe Generale SA, also sees a possible drag from apparel.

The BLS plans to collect more alternative data directly from companies, an avenue that could ultimately account for almost 32 percent the index, Konny and her colleagues outlined in a February paper. Examples include scraping fuel prices from the GasBuddy website.

That’s all a big change for an agency that, for more than a century, has constructed the CPI mainly from data it collected. U.S. inflation tracking has been evolving since the Revolutionary War, when Massachusetts adjusted militia pay based on prices for beef, corn, wool and leather, says Thomas Stapleford, an economic historian at the University of Notre Dame and author of “The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics.”

As the U.S. entered World War I, the BLS was charged with collecting cost-of-living data on major shipbuilding centers to set uniform national wages. Those emergency surveys, intended to prevent strikes, were rushed into use before they were ready, but later refined and expanded into a national consumer price gauge, Stapleford said.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeff Kearns in Washington at jkearns3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Scott Lanman at slanman@bloomberg.net, Brendan Murray

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.