Barton Draws on McKinsey Past to Help Teck ‘Withstand Torpedoes’

Barton Draws on McKinsey Past to Help Teck ‘Withstand Torpedoes’

(Bloomberg) -- When Dominic Barton was named chairman of Teck Resources Ltd., he was handed a rock hammer by Norman Keevil, his predecessor and controlling shareholder at Canada’s biggest diversified miner.

Inscribed: “Chair to Chair, 2018” it was an apt symbol for Barton, the former global managing partner of McKinsey & Co. who for decades chipped away at the ground-level for the corporations he advised, while maintaining a longer-term view from above.

“It’s kind of like having a telescope and a microscope and one eye,” Barton said in an interview, referring to a strategy that allows a business to invest for the long-term while delivering good results from quarter to quarter.

It’s the greatest challenge miners face: Assets take years to develop, and trying to time new production with strong commodity prices is a mug’s game. In Teck’s case, the near-term goalpost is pulling off the Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 expansion in Chile. Further out, global trends, including the move to electric vehicles and the inexorable ascendancy of Asia, are reshaping the markets in which Teck plays: metallurgical coal, base metals and energy.

“What’s happening in Japan, Korea, China of course, is still the single biggest determinant,” said Don Lindsay, 60, Teck’s chief executive officer. “Dominic, given his background, will be very good at asking those kinds of questions and leading those kinds of discussions.”

Rhodes Scholar

Barton has the global pedigree. Born in Uganda, the 56-year-old Rhodes scholar has lived in Asia, Europe and North America. On the day of the interview, he arrives at McKinsey’s Toronto headquarters from Singapore, via a stop in Vancouver for his first board meeting at Teck’s head office. It’s the 50th anniversary of McKinsey’s Canadian operations and the Toronto “ski chateau,” as the office is known for its surplus of wood and fireplaces, is filling up with more than 500 alumni from around the world.

Despite the din outside the cozy meeting room, Barton takes his time. He talks at length about the future of Asia and his greatest near-term fear: that the economic hit from a global trade war, coupled with rising interest rates, lead to stagflation and a Depression-era level of isolationism. Right now it’s more of a “tail risk,” but one for which Teck must be prepared. The good news is copper and met coal will always be needed, the miner’s balance sheet is strong, and Teck has weathered storms before.

“A key part of strategy is resilience,” he said. “It’s being able to withstand the torpedoes.”

Direct Hits

During his time at McKinsey, Barton has seen more than a few, including some direct hits. The firm recently emerged from a scandal involving contracts in South Africa and, just this month, was drawn into the issue of human rights in Saudi Arabia after the New York Times reported some of McKinsey’s work may have been used by the kingdom to silence dissidents. He’s also had a front-row seat for some of the biggest economic upheavals of the last 20 years; his time in South Korea coincided with the Asian economic crisis and he was in London during Brexit.

Through that, he’s proved himself “highly intelligent, disarming and bold,” says John Thornton, executive chairman of Barrick Gold Corp., who has known Barton for more than a decade. Both are adjunct professors at Tsinghua University in Beijing and Barton is a trustee at the Brookings Institution where Thornton is chairman.

Think Broadly

“He got people inside McKinsey to think more broadly than they had been doing,” Thornton said in a phone interview, citing its hiring practices for one. McKinsey receives 750,000 applications a year for 6,000 global positions. Barton has pushed to diversify its pool of young hotshot MBAs with mathematicians, veterans of other industries, and even candidates who haven’t been to university. “His starting point is: Why not? The starting points of many people are: No -- now persuade me.”

Neither Barton nor Thornton have previous mining experience, something both see as an advantage because they bring fresh perspectives. Thornton is also a fan of “family companies,” having seen that dynamic at work as a director at Ford Motor Co. and as chairman of Toronto-based Barrick. The Keevil family’s involvement in Teck is “an asset that Dominic will want to be very careful to husband,” he says. Norman Keevil, 80, and his family have been involved with Teck for almost 60 years and still control it through dual-class shares.

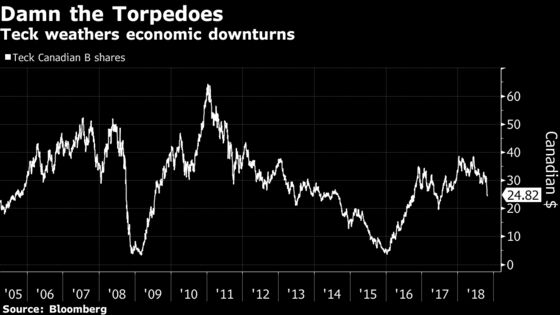

Those shares have seen some ups and downs with the commodities cycle. Under Lindsay’s almost 14-year tenure as president and CEO, the stock dipped below C$4 ($3.04) as recently as 2016. They’ve jumped six-fold since then to about C$25, even after a sell-off last week on disappointing earnings and a global market rout.

Just weeks into the job, Barton’s loathe to be specific about his plans for Teck. He hopes to leverage Keevil’s wisdom and says neither the family nor Teck’s dual-class structure are going anywhere. While Keevil stepped down as chairman Oct. 1, his son Norman Keevil III remains on the board as vice chairman.

Barton, on the other hand, is moving -- to Hong Kong where his partner is based -- though he plans to keep a residence in Vancouver. When he retires from McKinsey next August, he expects to pick up a few more board seats, continue to chair the Canadian minister of finance’s Advisory Council on Economic Growth, and to serve on the Singapore Economic Development Board’s International Advisory Council, ensuring he remains active on both sides of the world.

In 2017, about 60 percent of Teck’s revenue came from Asia, followed by Europe and the U.S., with just 8 percent from Canada. China’s sovereign wealth fund, China Investment Corp., is the largest holder of B shares even after cutting its stake by almost half a year ago.

Barton says Teck’s future is global, quoting from a presentation he gives on disruption. By 2030 there will be 2.4 billion new middle-class consumers, mainly in Asia and Africa, and the company needs to consider which commodities will offer the best opportunities in the future.

Potash to Cobalt

Uranium looks risky but could be a buying opportunity, as could food or potash or cobalt. The key is figuring out “where we think the demand’s going to be, who’s going to be going after that, where we think the reserves are and how much in capital we’re going to need,” he says.

It’s a contrast to Teck’s current messaging, which is very much about executing on a small number of key projects. Asked about the possibility of expanding into new commodities, Lindsay is adamant. “We’re not looking at anything like that; our priority is QB2,” he said, referring to the Chilean mine. “There’s no activity on the acquisition front at this stage.”

How much scope there is to push the “diversified” aspect of the company further remains to be seen, but Barton is clearly looking forward to discussions. Keevil, he says, has always viewed Teck’s board as a chamber of “sober second thought,” a term coined by Canada’s first prime minister to describe the country’s Senate.

Teck’s diversified portfolio and Canadian footprint give it a natural hedge in a world of rising trade tensions, Barton says.

“They define long-term.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Danielle Bochove in Toronto at dbochove1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Luzi Ann Javier at ljavier@bloomberg.net, David Scanlan, Steven Frank

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.