Banks Draw a Red Line on Negative Interest Rates in Sweden

Banks Draw a Red Line on Negative Interest Rates in Sweden

(Bloomberg) -- There’s an unspoken pact in Sweden between banks and monetary policy makers that may limit the Riksbank’s scope to cut interest rates.

According to Robert Bergqvist, a former Riksbank economist who now heads the economic research department at SEB AB, policy makers will avoid rate cuts that would force banks to pass the cost on to their retail depositors.

If the Riksbank decides to “go ahead and cut rates again, then we’ll end up in a situation where even household deposits will be hurt by negative rate,” Bergqvist, who’s based in Stockholm, said in an interview. “I think the Riksbank is afraid of that.”

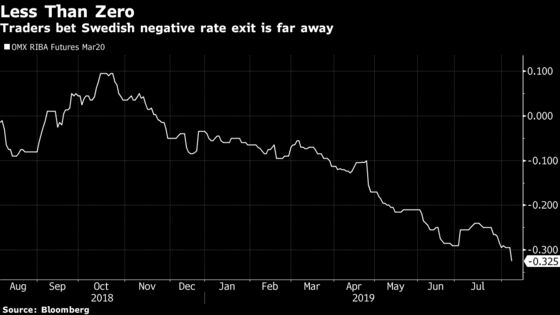

But with the world’s major central banks resorting to more monetary stimulus amid growing fears of a recession, the question is whether the Riksbank will have a choice. The bank has long signaled it’s keen to emerge from more than four years of negative rates, and already pushed through a quarter-point hike in December. Its main rate is now minus 0.25%.

Since then, the Riksbank has had to scale back its hawkish ambitions, and investors are now betting it will need to abandon its planned exit from extreme stimulus altogether.

What once was seen as a necessary evil to rekindle inflation risks becoming entrenched. As a result, banks are adjusting their business models to absorb the cost of long-term negative rates. But the longer the regime persists, the greater the risk that retail customers will be asked to share the burden. In Sweden, which has all but abandoned cash, the mechanics of imposing negative rates on deposits could pose extra challenges.

Cash Needed

Economic data since the Riksbank’s latest meeting have added pressure on the Riksbank to ease. Unemployment rose in June and economic growth unexpectedly contracted in the second quarter. Inflation is so far holding near the 2% target, but is anticipated to slow. Governor Stefan Ingves and his colleagues at the Riksbank have insisted they still have plenty of ammunition at their disposal should a new crisis hit. A spokesman declined to comment for this article.

Bergqvist says it’s inevitable that the financial system will come under a lot of strain if negative rates become the new normal. That’s especially true given that Sweden is a largely cashless society, meaning bank customers can’t avoid negative rates by stuffing their money under their mattresses.

“There just isn’t enough cash,” Bergqvist said. “This will lead to a lot of frustration. The Riksbank really needs to think things through before they take any steps like cutting rates further.”

Bergqvist says Riksbank policy makers will need to accept an inflation rate that doesn’t quite reach the target, rather than risk hurting banks more. The main responsibility in fighting a slowdown will instead fall on fiscal policy, he said.

The verdict on the effectiveness of negative rates has also been called into the question on the lending side. A study co-written by former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers argued that negative rates hurt bank profits and failed to translate into lower rates for consumers. The paper was disputed by the Riksbank.

“If I were to write the history book I would say that the Riksbank made a mistake going as low as they did by taking all these measures,” Bergqvist said. “A more flexible interpretation of the inflation target would have been a good thing.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Rafaela Lindeberg in Stockholm at rlindeberg@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jonas Bergman at jbergman@bloomberg.net, Tasneem Hanfi Brögger

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.