Babies and Rates: How Korea’s Low Birth Rate Adds to QE Case

A lack of newborns in South Korea could prompt the Bank of Korea to make baby steps into the realm of unconventional stimulus.

(Bloomberg) -- Explore what’s moving the global economy in the new season of the Stephanomics podcast. Subscribe via Apple Podcast, Spotify or Pocket Cast.

A lack of newborns in South Korea could prompt the Bank of Korea to make baby steps into the realm of unconventional stimulus.

That’s the view of S&P’s Asia-Pacific chief economist Shaun Roache, who points out that the demographic challenges of Korea’s rapidly aging society are giving the BOK less room for maneuver with interest rates.

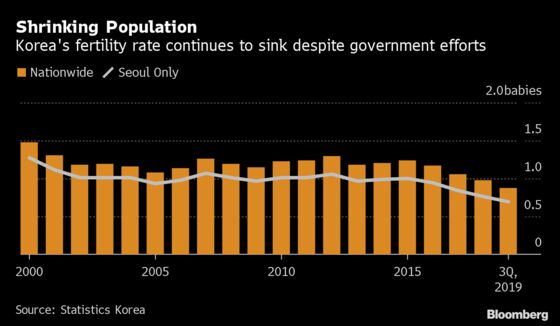

South Korea is on track to break its own world record for the fewest babies expected per woman, according to recent data. If the trend continues, the proportion of elderly citizens in Korea will increase by more than any other country by 2050, according to the United Nations.

This demographic challenge creates a reluctance to spend and a tendency to save more for retirement, especially with a pension system in Korea that is widely viewed as inadequate. This in turn pushes down the so-called neutral interest rate at which inflation is stable with full employment, Roache said in an interview in Seoul.

A low neutral rate means the central bank needs to go even lower to stimulate growth in the economy. The BOK is already concerned that it is close to a level where the side effects of lowering rates further could start to hurt the economy.

All this adds up to a case favoring consideration of non-conventional policy tools such as quantitative easing, Roache said.

“So the Bank of Korea now has to think about, if we need to ease policies, what else do we do,” Roache said. “I think they’ll have to start thinking about QE,” he said.

Governor Lee Ju-yeol said in October that it was too early to consider unconventional steps, though he also acknowledged that the BOK was constantly reviewing and updating contingency plans and studying actions previously taken by other nations should it run out of room to lower interest rates.

With the country’s inflation over the past year at 0.6%, the policy rate -- now at 1.25% -- would have to be lowered to 0.6% just to make monetary policy neutral, according to Roache. Already cautious policy makers in Korea are unlikely to go beyond that or toward negative territory given their concerns over the side effects of such moves on the banking sector, he said.

“My sense is that the BOK will probably think more about QE rather than negative rates,” Roache said. “Aging means low rates, which means that QE becomes a permanent part of the toolkit.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Sam Kim in Seoul at skim609@bloomberg.net;Jaehyun Eom in Seoul at jeom2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Malcolm Scott at mscott23@bloomberg.net, Jiyeun Lee, Paul Jackson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.