(Bloomberg Opinion) -- From the perspective of the rest of the world, Australia appears to be upside down. Its government budget, on the other hand, is back to front.

Superficially, the A$158 billion ($111 billion) tax cut package passed by the country’s House of Representatives Thursday looks like just the sort of measure needed for an economy crashing to earth.

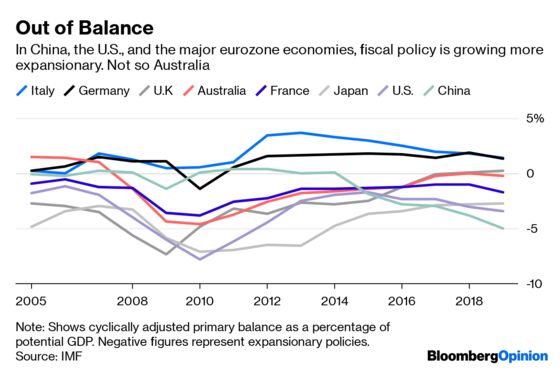

There’s just one problem. Unlike the rest of the world, where fiscal policy is becoming more expansionary after years of belt-tightening, Canberra is saving the majority of its stimulus for a later date.

Unemployment in Australia has ticked up to its highest level in nine months, and broader measures remain at the elevated levels they’ve been at for five years.

In the first quarter, gross domestic product grew just 1.8%, the slowest pace since the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Australia hasn’t had two consecutive quarters of contracting national output, the technical definition of a recession. But in per-capita terms, growth has been going backward for three quarters in a row. Worse could be round the corner if trade wars and a slowing Chinese economy hit exports of coal and iron ore.

An economy in that shaky condition looks in need of a shot in the arm from the newly re-elected government. Unfortunately, that doesn’t appear to be on the cards.

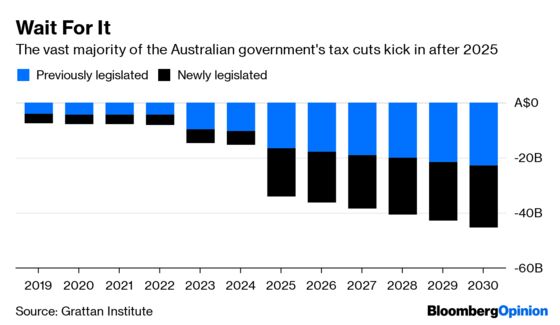

Just A$7.7 billion, or 3.1% of the 10-year tax cut package, will kick in over the 12 months through next June, according to analysis by the Grattan Institute, a Melbourne-based think tank. About the same amount will follow in each of the subsequent three years, before rising to A$15 billion in 2023. Some 84% of the total, though – A$207 billion – will come in the subsequent six years.

Who knows what will be happening to the Australian economy that far into the future? One thing we can be sure about: The money would be better spent now.

As my colleague Daniel Moss has written, Australia’s reputation as a country that’s escaped the boom-and-bust business cycle should be consigned to the past. Investors are already treating it as an anachronism. The yield on 10-year government bonds has been cut in half since the start of December to 1.29%, and the Reserve Bank of Australia has taken its policy rate down 50 basis points to 1% since the start of June.

Even quantitative easing – a measure that would have been unthinkable in Australia a decade ago, when it was being rolled out across the northern hemisphere – could now be on the cards, though the Reserve Bank has poured cold water on the idea.

The reason such extreme measures are being contemplated for Australian monetary policy is that fiscal policy isn’t doing its job. Far from moving to stimulate the economy as it weakens, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg is determined to return the budget to a modest surplus of A$7.1 billion in the current budget year, and remain in the black over the following three.

That appears to be exasperating Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe. “We should not rely on monetary policy alone,” he told an event in Darwin on Tuesday. “We will achieve better outcomes for society as a whole if the various arms of public policy are all pointing in the same direction.”

There are other issues with the tax cut package. Half of the benefits will go to the top 20% of earners, giving Australia its least progressive income tax system since the 1950s, according to Grattan. The cuts for the richest Australians are so large that the government will have to push spending growth to its slowest in a generation if it’s to keep the budget in surplus into the late 2020s.

Still, measures of that sort are to be expected from a right-of-center government. What’s harder to explain is the commitment to a budget surplus few voters seem to care about. Frydenberg and his colleagues no doubt have fond memories of how attacks on the deficits run up by the then-Labor government in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis helped propel their return to power in 2013. An electorate that considers the economy its biggest worry is less likely to care, so long as it’s seeing some growth.

“If the economy starts to head south you don't want a government just focused on the objective of a surplus,” said Danielle Wood, Grattan’s budget policy director. “You want a government that's ready to stimulate.”

Such policies don’t look like they’ll be happening any time soon. That’s a decision that the government of Prime Minister Scott Morrison, facing fresh elections in three years, may live to regret. Australia’s economy badly needs some medicine right now. A spoonful of sugar wouldn’t go amiss, either.

We've based our figures on Grattan's estimates of the budget impact over the 10 fiscal years starting July 2019 and ending June 2029. About half of the cost comes in measures that had already been legislated; the laws passed Thursday represent the other half of the A$246 billion total for the period. The numbers differ from the government's A$158 billion price tag.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.