Australia Needs to Update Lesson From the ‘Banana Republic’ Years

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s never a banana around when you need one.

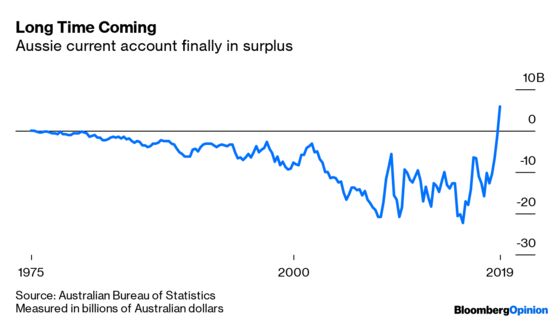

The deficit in Australia’s current account, the broadest measure of trade, has vanished. Even if the surplus reported Tuesday for the second quarter, the first since 1975, is temporary, this one-time bogeyman of an indicator has been trending toward balance for the past decade or so.

Yet this moment for the history books isn’t getting the attention it warrants. That’s a pity, because after 27 years without a recession, the country could use the sense of crisis that the current-account deficit generated in the 1980s.

The reforms to contain the deficit set Australia on course for its record growth run. The key ideas: spur exports, rein in the budget, control wage growth, lick inflation, steady the currency and, by implication, elevate the Reserve Bank of Australia to its role at the pinnacle of decision making. Demand for Australian resources during China’s boom years also played an important role.

Today, the concern isn’t about an overheating economy sucking in too many imports and a yawning current-account deficit weakening the local dollar. The challenge now is, how to keep the long expansion alive and with what type of fiscal and monetary mix?

The RBA is doing its part, trimming interest rates to just 1%. Fiscal policy seems stuck, unresponsive to the idea that the central bank can’t go it alone. A budget in the black has become such a central organizing principle that it’s fair to ask whether in the drive to repair the current account, the wrong lessons have been learned.

One era’s totem isn’t another’s. To appreciate why the sense of urgency is sorely missed, a quick trip back to 1986 is required. It was the year that Chernobyl melted down and Iran-Contra came to light, but in Australia it’s remembered for Paul Keating, then the treasurer and later prime minister, who put “banana republic” into the vernacular and communicated his sense of urgency about the economy to ordinary Australians.

Keating had been raising the red flag on the widening trade deficit, but no one was paying attention. The dollar, floated only a couple of years earlier, was under pressure. In response to figures showing the April current-account deficit widening yet again, Keating dialed in to a talk-radio show from a kitchen phone at a party fundraiser to express his frustration and alarm.

The remarks that followed, as recounted by Kerry O’Brien in his 2015 book, “Keating,” became legendary. In years of listening to finance ministers from major economies, I don’t recall hearing stuff like this often:

“It means an internal economic adjustment, and if we don’t make it now we will never make it. If the government cannot get the adjustment ... and a sensible economic policy, then Australia is basically done for. We will just end up being a third-rate economy.”

Minutes later, in response to a question, Keating entertained the prospect the country would be “gone, you know, you’re a banana republic.” Forget technocratic caution. All hell broke loose and the dollar swooned. But, in retrospect, the remark had the desired effect because it forced politics and business to embrace a series of policy goals that remain largely intact today.

Australia was then struggling to adjust to deregulated markets, an exchange rate freed from shackles and the idea that protectionism was sub-optimal. Now, it is seen abroad as some kind of economic template, a role model to be studied and even emulated. Few people inside Australia, concerned over house prices or wages, think things are that great.

Fighting the current-account deficit may have outlived its usefulness, though you’d never know it from government reflexes. Few want to show a budget in deficit for very long, regardless of the economic environment and how little it costs to borrow. Woe betide a treasurer who doesn’t genuflect to “AAA” sovereign credit ratings. Successive leaders, regardless of party, worship at the altar of free trade.

These things have become talismans, but different eras require different prescriptions. There’s no sin in using government funding to boost demand when growth is slackening.

The familiar cry of central bankers everywhere that they could use a hand in buttressing growth needs to be answered. Granted, the current government has embarked on tax cuts, but they won’t seriously kick in for years. And it’s great to be all for expanding overseas markets and exports, but there’s little appetite these days for broad trade accords that big powers can sign. The debate seems stale.

Economies and the international context that they operate in evolve. Fixating on prescriptions from the current-account crisis years could undermine health now. The global economic climate is cooling. Let’s boost demand at home, not extinguish it.

The ’80s were a golden era of policy making. What a pity if those settings become so rigid that the very expansion they established is jeopardized.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Patrick McDowell at pmcdowell10@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies. Previously he was executive editor of Bloomberg News for global economics, and has led teams in Asia, Europe and North America.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.