As China Markets Plunge, Here's How Vital Signs Look Versus 2015

Is 2015 all over again?

(Bloomberg) -- China’s stocks are tumbling, the yuan is sinking, and a government-backed think tank is warning of a potential financial panic.

Is this 2015 all over again?

Given the dramatic moves in Chinese markets over the past week, it’s only natural to draw comparisons to the equity crash and yuan devaluation that rattled investors worldwide three years ago. There are certainly some similarities between now and then, but there are also key differences -- including cheaper equity valuations and a less interventionist response by Chinese authorities.

Below is a rundown of how today’s environment stacks up against that of 2015.

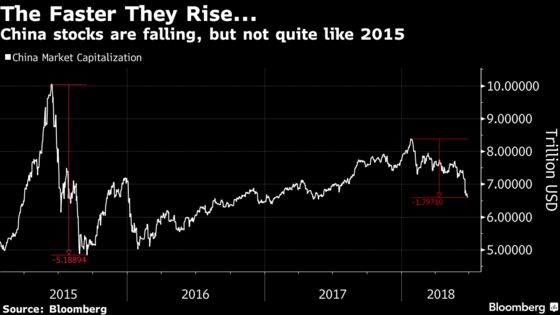

Scope of declines

Chinese stocks have lost almost $2 trillion in five months. That’s nothing to scoff at, but the pace of declines has yet to match the market’s gut-wrenching selloff in 2015. That crash erased $3.2 trillion in its first three weeks, or almost $1 billion for each minute of trading. While the Shanghai Composite Index sank more than 8 percent in a single day in August 2015, its worst session in recent weeks was the 3.8 percent drop on June 19.

The picture is similar for the yuan. The 2015 devaluation triggered a nearly 3 percent drop in just two days, shocking global investors who had grown used to a stable Chinese currency. The latest slump is comparable in magnitude, but the yuan has taken about two weeks to get there. The offshore currency was slightly weaker in Hong Kong early Thursday, after falling for 10 straight days.

Stock valuations

Before its 2015 crash, China’s equity market was in the throes of a classic speculative bubble. The Shanghai Composite had a forward price-to-earnings ratio of 19, and hundreds of shares in the index traded for multiples that exceeded 100.

The index is now valued at 10.5 times projected earnings, lower than at any time since the end of 2014. By some measures, it’s the cheapest on record versus the S&P 500 Index.

Economic backdrop

Hard landing or soft: the debate over whether Chinese policy makers can prevent a steep economic downturn has been raging for years. Growth was decelerating in 2015, but the central bank was very much in easing mode -- cutting interest rates and pumping gobs of money into the financial system.

This time, authorities seem less willing to open the taps. While the central bank announced a cut to lenders’ reserve requirements this week, policy makers are wary of backtracking on a high-profile clampdown on financial leverage. There’s also the wild card of rising trade tensions: Donald Trump’s threat to impose tariffs on another $200 billion of Chinese imports could cut as much as half a percentage point from the nation’s economic growth, according to economists.

Global reaction

International investors have largely shaken off this year’s rout in Chinese stocks. But the yuan has definitely grabbed their attention. One sign of the spillover effect: an index of firms in developed markets that get the most sales from China, including Qualcomm Inc. and Rio Tinto, has dropped about 7 percent since the yuan’s decline kicked into high gear in early June.

Still, the global impact was far greater in 2015, when China’s surprise devaluation sparked concern that other emerging-market countries would follow. The move triggered the first 10 percent correction in the MSCI All-Country World Index of global stocks since the peak of Europe’s sovereign-debt crisis in 2011. The Bloomberg Commodity Index slumped 25 percent amid fears of sinking Chinese demand, its biggest annual decline since 2008.

Market intervention

While China’s government routinely intervened in foreign exchange and stock markets in 2015, authorities appear to be taking a less heavy-handed approach these days. Yes, they’ve meddled around the edges -- publishing stronger-than-estimated reference rates for the yuan and asking brokerages to refrain from sudden liquidations of shares pledged as collateral for loans. But they’ve so far avoided massive interventions of the sort that whipsawed traders a few years ago.

“We know that China will want to avoid any similarities to 2015,” said Timothy Graf, a macro strategist at State Street Corp. in London. “They’re allowing markets to do their thing, having learnt that a heavy hand doesn’t work.”

Leverage

Back in 2015, it was retail margin traders who had everyone worried about China’s stock market, and for good reason. Outstanding margin loans on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges topped $350 billion at their peak. When the bubble burst, losses snowballed as traders were forced to sell shares to meet margin calls.

While margin debt has since shrunk by more than half, a new kind of leveraged investor has stepped into the fold. More than $770 billion of Chinese shares, or about 12 percent of the country’s market capitalization, have been pledged as collateral for loans, according to data compiled by China Securities Co. and Bloomberg. The pledges, popular among company founders and other major shareholders in need of cash, have become a growing source of concern for analysts as stocks have tumbled in recent weeks.

All told, leveraged purchases of shares have reached levels last seen in 2015, according to a study by China’s National Institution for Finance & Development, a government-backed think tank.

Capital outflows

Three years ago, it looked like China might get caught in a never-ending spiral of capital outflows, a weakening yuan, and still more outflows. An estimated $1.7 trillion left the country in 2015 and 2016.

This year, there are few signs of a repeat of that exodus. That’s partly because China has tightened capital controls. But it also helps that Chinese home prices are still climbing in most big cities. Real estate makes up a large chunk of household wealth in China, and as long as values are rising there’s less of an incentive to spirit money overseas. That said, the yuan has only recently started to weaken. The outflow picture could change quickly if losses continue.

To contact the reporter on this story: Sofia Horta e Costa in Hong Kong at shortaecosta@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Richard Frost at rfrost4@bloomberg.net, Michael Patterson

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.