Abenomics Shows ECB Why Fiscal Backup Can’t Ensure Inflation

Abenomics Shows ECB Why Fiscal Backup Can’t Ensure Inflation

(Bloomberg) --

When Mario Draghi ended his term as European Central Bank president last week with a call for government policies to be “mutually aligned” with those of his institution, the message came with an unspoken caveat -- it might not be enough.

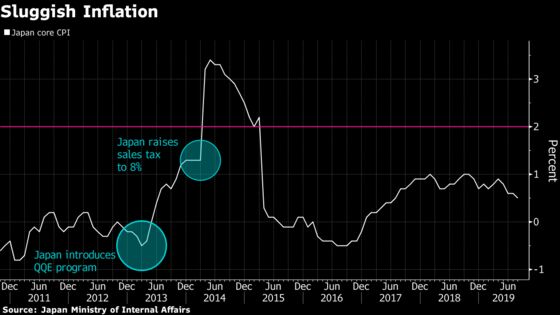

Japan has been attempting such monetary-fiscal coordination since 2013, with a joint statement by the Bank of Japan and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration pledging to work toward 2% inflation and sustainable economic growth. Under Abenomics, as it’s known, the price goal was supposed to be achieved in just two years. Six years on, inflation is stuck below 1%.

Abenomics followed two decades of deflation dating back to the bursting of an asset-price bubble in the 1990s. Like the ECB, the BOJ used interest-rate cuts and quantitative easing to pump money into the economy, a strategy that helps the government finance its expansionary budget.

It’s been a partial success. Yoshinori Shigemi, a global market strategist for JPMorgan Asset Management Japan Ltd. in Tokyo, reckons the program boosted economic growth largely by weakening the yen, making exports more lucrative as the global economy expanded. Unemployment dropped to a record low, propping up political support, though the impetus is facing headwinds as the world economy cools.

“The fiscal effect was there at the beginning of Abenomics, but it hasn’t lasted,” Shigemi said. “More recently, the Abe administration itself has been in a state of self-satisfaction.”

Japan did extract itself from deflation, yet it hasn’t managed to get price growth to stick. The BOJ highlighted its struggle only last week when it changed its policy language to say interest rates might need to fall again.

That’s similar to the ECB, where Draghi cut rates below zero in 2014 and soon after started QE to stave off a damaging downward spiral in prices and wages. Asset purchases were capped at the end of 2018 but in September, as global trade tensions exposed the euro zone’s economic frailties and consumer prices weakened, he cut rates again and restarted buying bonds.

Stepping into Draghi’s shoes this month, President Christine Lagarde has inherited an inflation rate at less than half the goal of just under 2%. The ECB’s forecasts don’t envisage a return to the target until at least late 2021 -- and, like the BOJ, such projections have consistently been over-optimistic.

“Low interest rates are not delivering the same degree of stimulus as in the past, because the rate of return on investment in the economy has fallen. Monetary policy can still achieve its objective, but it can do so faster and with fewer side effects if fiscal policies are aligned with it.”

-- Mario Draghi in Frankfurt, Oct. 28

The lesson isn’t that fiscal-monetary coordination doesn’t work, according to Harumi Taguchi, Tokyo-based principal economist at IHS Markit. It’s that the measures must properly address the economy’s weaknesses, and be big enough to tackle them.

Japan expects a budget deficit of 2.7% this fiscal year, and is reluctant to do more because of its total public debt burden -- the largest among developed nations at more than 200% of GDP. The government actually has a medium-term goal of balancing the books, though that keeps getting pushed back. Moves to boost revenues, such as a sales tax increase in 2014, have reduced consumption. Another such hike in October is being closely watched for its impact.

“Given the current tax structure, unless there’s another crisis of the scale of 2008, it’s difficult for Japan to spend while significantly increasing its budget deficit,” Taguchi said.

Euro-area governments, scarred by the region’s debt crisis this decade, feel similarly constrained even with a much lower debt-to-GDP ratio at 86%. Draghi has repeatedly said his loose policy buys room for governments to act, yet the bloc’s overall fiscal stance is only mildly expansionary and Germany, the biggest economy, continues to run a surplus.

Abe’s administration may also have been insufficiently bold with structural reforms to raise growth potential. Euro-zone nations have likewise been slow in that respect, putting off socially painful adjustments. The ECB repeatedly says efforts to boost productivity, reduce structural unemployment and boost resilience must be “substantially stepped up.”

Other nations have had more success than Japan in coordination. Norway’s fiscal support helped allow the central bank to raise rates four times in the past year, and Governor Oystein Olsen said the interplay between fiscal and monetary policy will likely allow negative rates to be avoided.

Norway is a single small economy though. The euro zone faces a bigger challenge: 19 member states with culturally different approaches to such key financial tools as debt.

At his farewell ceremony, Draghi cited the U.S. as an example of a nation where fiscal support allowed the central bank to move away from the extraordinary monetary policies that dominated the decade after the global financial crisis.

Perhaps wisely, he didn’t mention Japan.

To contact the reporter on this story: Yuko Takeo in Frankfurt at ytakeo2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Brian Swint

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.