Abenomics Champion Bows Out as Japan Seeks Post-Pandemic Reboot

Abenomics Champion Bows Out as Japan Seeks Post-Pandemic Reboot

(Bloomberg) -- Taro Aso on Monday leaves his post as Japan’s longest serving finance minister in modern times.

He exits as the ruling party attempts to reboot with a new cabinet amid public dissatisfaction over its handling of the pandemic. Aso’s departure marks another step away from the Abenomics experiment that helped spur periods of economic growth, but couldn’t deliver sustained income gains or cut the aging nation’s massive debt pile.

After nearly nine years on the job, Aso is replaced by his 68-year-old brother-in-law, Shunichi Suzuki, a former Olympics minister and ruling party lawmaker who helped install Japan’s new premier, Fumio Kishida.

Kishida, after winning a party leadership vote last week, said he wanted to appoint younger lawmakers to key positions, in an attempt to freshen up the government before national elections this fall. After being made prime minister on Monday, Kishida formed his cabinet and replaced the 81-year-old Aso.

In his final press conference as finance chief earlier Monday, Aso said his successor was an experienced policy maker who might do a better job of explaining things to the public than he had.

Aso himself had a short stint as premier between 2008 and 2009, but will be remembered more for his years as finance minister and deputy prime minister, first under former premier Shinzo Abe and then under Yoshihide Suga.

In that role, he coordinated the “Abenomics” policy with the Bank of Japan, which bought record amounts of government bonds as part of a stimulus program that drove down the currency and temporarily lifted inflation.

“You could say that he provided steady support for the Abe administration, by providing consistency within a long-term policy approach,” said economist Harumi Taguchi at IHS Markit.

The policy, however, didn’t succeed in getting the economy out of its slow growth or generating the sustained price gains promised.

Aso often criticized Japan Inc. for hoarding cash rather than boosting investment and wages, but failed to get much change to happen.

Kishida, for his part, has dangled the idea of a “new type of Japanese capitalism,” favoring redistribution and pay increases, but has only sketched the outline of how he’ll get it done.

To pay for rising social security costs as Japan’s population aged, Aso oversaw two hikes in the sales tax that doubled the levy to 10%. The increases helped boost revenue, but also triggered recessions in 2014 and 2019.

Higher revenues also didn’t stop Japan’s budget deficit from widening even in years when the economy was expanding as the inevitable growth in social security costs drove up spending.

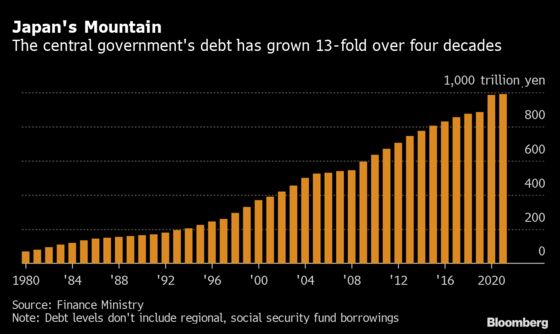

Over the near-decade that Aso has been in charge of Japan’s finances, government debt has risen to above 250% of gross domestic product. Even with central bank bond purchases keeping interest rates near zero, debt payments consume almost a quarter of the budget.

In his final year, Aso oversaw record borrowing as the world was hit by Covid-19. Three extra budgets meant an additional 80 trillion yen ($720 billion) of new bonds issued, adding to Japan’s already enormous debt pile.

While it’s unclear whether Suzuki or Kishida might bring fundamental changes to economic policy, they will be left with the task of dealing with the country’s fiscal imbalances.

The government has a goal of balancing its budget by the year ending March 2026. The target excludes the costs of paying for debt, but is still seen as unreachable this decade even by the government’s own projections.

The first order of business for Kishida’s new administration will be preparing for the upcoming election, and that likely means additional stimulus.

Kishida has said that tens of trillions of yen must be spent in the near term to support the recovery. Economists including Masaki Kuwahara at Nomura Securities expect a stimulus package of about 30 trillion yen.

Longer term, Kishida has talked about distributing wealth more equitably, and seeking to jump-start a virtuous economic cycle by raising public sector wages. Last week, he singled out nurses, caregivers to the elderly and kindergarten workers as having too low a wage, signaling he’ll attempt to boost their paychecks.

The new finance minister is unlikely to follow Aso’s record in one area -- his penchant for gaffes and insensitive comments such as saying Adolf Hitler had “correct motivations” and blaming childless people for Japan’s societal woes.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.