A New Urban Divide and Other Gems From the Big Economics Shindig

A New Urban Divide and Other Gems From the Big Economics Shindig

(Bloomberg) -- Frank Sinatra famously sang of New York, "if I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere." But the promise embedded in his lyric -- the idea that cities offer an on-ramp to success -- is no longer true for less-educated Americans.

As recently as the 1980s, people had a better shot at working in clerical, administrative and sales jobs if they lived somewhere with higher population density, and those middle-skill positions paid more in cities than they would in the countryside. These days, there are few middle-skill jobs available anywhere, and they’re actually rarer in metropolises.

While women can still earn more if they manage to find middle-skill work in a densely populated place, non-college men have seen the wage premium collapse.

“It’s not clear where the land of opportunity is for non-college adults,” said Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist David Autor, who presented his findings during a lecture at the American Economic Association annual meeting in Atlanta on Jan. 4.

(You’re reading Bloomberg’s weekly economic research roundup.)

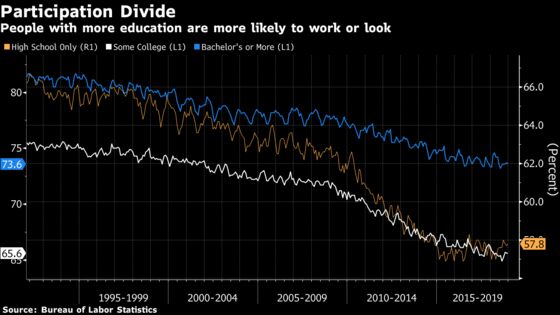

The idea that moving to achieve a better economic life is no longer much of an option for people without a college degree matters. The trend could be deepening the economic divide between superstar cities and everywhere else, fueling social division in a nation where everything from labor market attachment to political party affiliation splits along educational fault lines.

Importantly, workers who have gone to college still do better in densely populated places.

Cities have become more educated and comparatively younger as members of Generation X and the Millennial generation -- groups with high college attendance -- moved in to find great jobs and often stayed put. That happened at the same time as their less-trained counterparts stayed away. In 2015, the gap in college attainment between urban and rural areas reached a staggering 20 percentage points, Autor found, up from 8 percentage points in 1980.

Cities were six years younger than rural regions in 2010, marking a total inversion from 1950, when the urban median age was five years higher. The findings took many economists at the gathering by surprise, including, apparently, Autor himself.

“I expect that the fall in geographic mobility means something different from what I had come to understand -- I had understood it as a reflection of barriers to move, barriers to opportunity,” Autor said.

| Here are other presentations that caught our eyes at AEA this weekend... |

In a presentation that generated buzz on Twitter, Peterson Institute economist Olivier Blanchard presented a paper that concluded that high public debt is bad but "not catastrophic." He suggested that governments ought to set a rule for themselves: If they see that markets are losing faith in their ability to pay, they should "aggressively" run budget surpluses to reduce debt, proving their ability and willingness to pay what they owe.

While it makes sense to take on debt in recessions and when infrastructure investment is needed, he said, the risk is that bondholders will get nervous and demand higher rates -- making holding debt more expensive. That’s a distant fear for the U.S., which owes almost all its debt in its own currency.

The presentation is noteworthy because it plays into a growing debate in the U.S. over whether running large and consistent deficits is actually problematic. A small-but-growing group of Modern Monetary theorists argue that under certain conditions, public debt has big benefits and limited drawbacks.

The video-games-vs-work saga continues. U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency economist Gray Kimbrough finds that young men have dramatically increased the amount of time they spend gaming over the past 15 years, but it probably isn’t driving them to drop out of the workforce in the first place. "While non-employed men who recently left jobs play slightly more video games, on average, than employed men, they play significantly less than non-employed men who did not recently transition out of employment."

Kimbrough thinks it’s more likely that labor demand issues are keeping young men sidelined. For an alternate viewpoint on how better leisure activities might keep folks on the sidelines by raising the wage at which they’ll jump back into the workforce, check out this Mark Aguiar and Erik Hurst paper from last year.

To contact the reporters on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net;Peter Coy in New York at pcoy3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.