A Decade After Financial Collapse, Iceland Faces a New Crisis

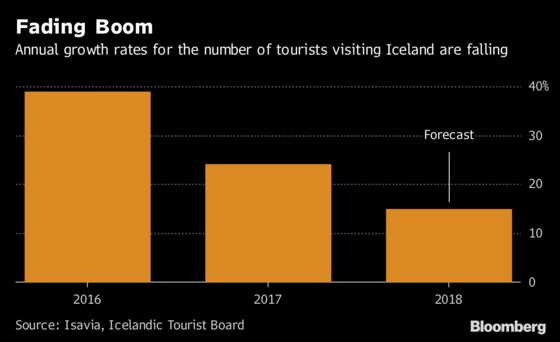

The number of people visiting Iceland rose nearly 40 percent in 2016 but only 24 percent in 2017.

(Bloomberg) -- Just as Iceland looks back at a decade of recovery since its financial and economic collapse, the north Atlantic island is once again grappling with an existential challenge for one of its key industries.

Tourism and the foreign cash it provides was instrumental in digging the 340,000-person nation out of its deep hole. Now, the industry is cooling fast and problems are mounting for its airlines after years of rapid expansion. Rewind to 10 years ago, and a similar tale could be told about the nation’s banks.

Arion Bank hf, in a report called “Tourism in Iceland: Soft landing or a belly flop,” warned the nation could face falling numbers of visitors next year after a boom that saw arrivals more than quadruple over the past decade. Tourism is the largest “export” and accounts for 12 percent of gross domestic product and about 20 percent of business investments, according to Arion.

The spillover from a tourism crisis could affect the whole economy, including “demand for labor, investments in hotels, the current account balance, the exchange rate of the krona, and so on,” said Gylfi Magnusson, an associate professor at the University of Iceland.

And the cooling is most apparent on the front-lines of the industry. The Icelandic carriers have encountered turbulence as other Nordic operators are squeezed by higher oil prices after embarking on ambitious planes to grab a slice of the trans-Atlantic travel market.

Icelandair Group hf was this week forced to seek the help from bondholders after issuing a profit warning and seeing its chief executive officer quit two months ago. The Reykjavik-based airline had hoped for a rise in European airfares that never materialized.

Wow Air

Wow Air Ehf, a rapidly growing low-cost carrier that together with Icelandair brings the majority of tourists to Iceland, has been the subject of a whirlwind of speculation as it raised new cash through a bond issue. It has canceled flights to Edinburgh, Stockholm and San Francisco over the winter, citing delays in the delivery of two Airbus A330neo aircraft.

Such delays were also cited by Primera Air, another Nordic carrier, as it filed for bankruptcy this week. Norwegian Air Shuttle ASA, a pioneer in low-cost trans-Atlantic flights, has meanwhile cut more routes as it grapples with costs and a stretched balance sheet.

The troubles haven’t gone unnoticed at the central bank. It was last month forced to intervene in the currency market to prop up the krona, which tumbled amid concern over the financial situation at Wow Air.

Krona Slumps

The currency slumped as much as 1 percent on Wednesday following Icelandair’s revelation.

“It is no secret that airlines, in particular here in the North Atlantic, are now dealing with a more difficult operating environment than before,” Central Bank Governor Mar Gudmundsson said in an interview in Reykjavik on Wednesday. “Oil prices have almost doubled in a year and the competition in this market is great.”

In addition, Icelandic companies are lumbered by significant salary increases when measured in foreign currency, he said.

IMF Warns

The trouble come against the background of a slowdown in tourism, which according to central bank forecasts will no longer dominate Icelandic exports in 2019.

The number of people visiting Iceland rose nearly 40 percent in 2016 but only 24 percent in 2017. In these two years, the economy grew at an annual rate of 7.4 and 4 percent respectively. This year’s annual increase is expected to be 15 percent, according to airport operator ISAVIA.

Last month, the International Monetary Fund said the effects of a strong krona between 2014 and 2016 were now being felt on tourism growth and domestic demand. It listed strong oil prices, mounting competition in the air transport sector, “escalating world trade tensions” and “uncertainty around Brexit negotiations” among the potential risks facing the economy.

But Governor Gudmundsson rejects any comparisons with the banking crisis of 10 years ago.

“Those were totally different events and occurred in the financial system and in banks which can be subject to bank runs,” he said. “Companies are constantly taking risks and some take more risk than others.”

--With assistance from Christopher Jasper.

To contact the reporters on this story: Ragnhildur Sigurdardottir in Reykjavik at rsigurdardot@bloomberg.net;Nick Rigillo in Copenhagen at nrigillo@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jonas Bergman at jbergman@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.