A Big Fight Lies Ahead for U.S. Labor to Lock In Pandemic Gains

A Big Fight Lies Ahead for U.S. Labor to Lock In Pandemic Gains

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

At the start of the pandemic, American workers were thrown out of jobs by the millions. By the time it ends, they could be in their strongest position in decades.

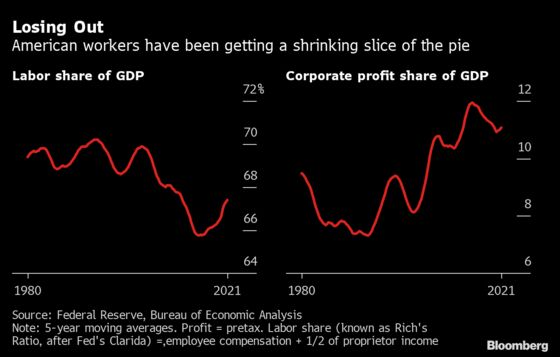

Union leaders and labor economists caution that the big battles have yet to be won -– but they can see conditions in place for workers to claw back some of the ground lost during the U.S. economy’s long slide into inequality. Since the 1980s, wages have lagged as corporate profits and stock markets soared.

Now, there’s a president who sounds more labor-friendly than his recent predecessors, a Federal Reserve that seems willing to let wages run hot, and a public that’s grown more appreciative of low-paid service workers.

Jobs lost to Covid are coming back -- often with better salaries than before. The August employment report, due out on Friday, is forecast to show more than 700,000 people added to payrolls, and corporate giants from Amazon.com Inc to McDonald’s Corp. have been raising pay.

In the rush to reopen, bosses have needed to hire like never before, and that’s given workers some bargaining power. Many have also been re-examining work and life after the Covid-19 trauma –- and discovering they have options. There’s a record number of job openings, and expanded benefits have given workers a financial cushion so they can wait a bit longer for the right opportunity.

Unchanneled Power

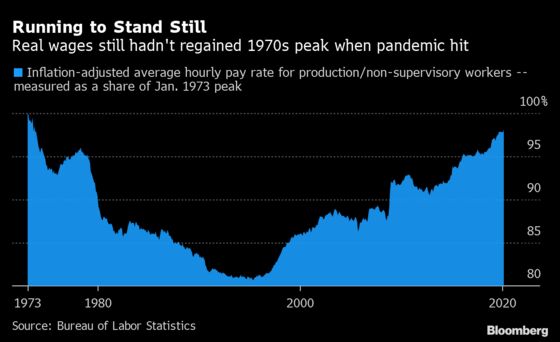

There’s something fragile about all these gains, though. The extra $300-a-week unemployment payments will end this month, right on Labor Day. It’s not clear how long the momentum for higher wages will last. And the long-term trends aren’t encouraging. On the eve of the pandemic, hourly pay for most workers -- after adjusting for inflation -- was still below its 1973 peak. Union membership, as a share of the labor force, is less than half what it was back then.

“The power that people are talking about that workers have right now is really unchanneled, unfocused –- and will be fleeting if we don’t organize,” says Sara Nelson, president of the Association of Flight Attendants-CWA, who’s become one of America’s most prominent union leaders.

Labor is hoping President Joe Biden’s administration will help make that happen.

Biden, a longtime union ally, signaled at a CNN town hall earlier this year that his administration might take a more worker-friendly approach. When a restaurant owner complained that higher jobless benefits were deterring people from applying for jobs, the president told him that the industry was just going to have to pay more.

“Worker power is unique right now,” says Biden’s Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, the first union member to hold that post in half a century. “There are so many companies really trying to get people back into the workplace.”

‘You Need Both’

But some of the administration’s plans have hit the rocks. A bid to raise the national minimum wage to $15 an hour fell foul of congressional rules. The Protecting the Right to Organize Act, labor’s top legislative priority, would make it easier to form unions, strengthen the right to strike, and convert many independent contractors to employees with full workplace protections –- but it’s stuck in the Senate, unlikely to get past a filibuster.

Without such measures, there’s a risk that any gains will be eroded when the business cycle turns down. Labor suffered a defeat when Amazon warehouse employees in Alabama voted against forming a union, though a legal challenge is under way, and the spread of so-called “gig work” has also made organizing harder.

Anna Stansbury, an MIT economist who’s studied the waning influence of U.S. labor, says worker power operates via two channels: tight job markets, and formal structures like legislation and unions. “You need both of those,” she says.

New thinking at the Fed should help on the first count. Wages had started to pick up before the pandemic, as the central bank cut interest rates to ward off a slowdown even with unemployment below 4%. Since then, that less hawkish approach has been enshrined in a new framework that will keep rates low to support the post-pandemic recovery in jobs and wages.

Still, Stansbury says it will take “a whole range of different measures, and a long period of tight labor markets,” to restore the clout that workers have lost over four decades or so.

‘Put In a Floor’

Historically, better deals for labor haven’t just materialized because presidents, legislators or Fed officials decided they were appropriate. They’ve been fought for. And there’s been plenty of that during the pandemic too.

While government officials only counted eight “major stoppages” -- those involving at least 1,000 workers and lasting one shift or more -- in all of 2020, there’s been a wave of smaller-scale strikes and walkouts that’s carried on into this year.

Researchers at Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, who’ve built a database to track labor actions starting late last year, identified 50 strikes and 167 “labor protests” in the first quarter of 2021 alone. Along with better pay and health-insurance benefits, workplace safety during the pandemic was one of the most common triggers.

It always comes down to organized action, and protections squeezed out of politicians, to advance labor’s cause, according to Larry Cohen, a former president of the Communications Workers of America. Swings in the business cycle, like the one that’s pushing wages up right now, might give workers a helping hand at times -- but they can’t be relied on for lasting progress.

“Markets have never taken care of working people. Ever. Anywhere,” says Cohen. “You have to put in a floor. It has to be done by workers and by government. Otherwise, most people get screwed.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.