A 19th Century Theory Explains Why Consumers May Not Splurge

A 19th Century Theory Explains Why Consumers Might Not Splurge

(Bloomberg) -- Discover what’s driving the global economy and what it means for policy makers, businesses, investors and you with The New Economy Daily. Sign up here

Consumers who saw their savings jump during the pandemic might be deterred from splashing out as the economy recovers if a 19th-century theory holds.

European Central Bank policy maker Pablo Hernandez de Cos raised the prospect of so-called Ricardian equivalence in a speech last week that addressed how the pace of consumer spending will contribute to the economic rebound.

Named after British political economist David Ricardo, the theory states that people assume they’ll ultimately have to pay for the government’s budget. Hernandez de Cos, who heads the Bank of Spain, said consumers might hold back in anticipation of higher taxes after governments increased their debt burdens in the Covid-19 crisis.

“We can’t rule out that in Spain and other countries, as a consequence of the deterioration in public finances, that what we economists call a Ricardian effect could occur,” he said.

Policy makers are keen to understand how European consumers will behave after the pandemic. Savings have risen in part because access to travel and leisure has been restricted, while some workers’ wages have been protected by furlough programs. A spending spree would turbo-charge the recovery.

Bloomberg Economics reckons the euro zone’s biggest economies boosted excess savings by 387 billion euros ($464 billion) last year. Oxford Economics estimates excess savings accumulated by euro-area households could reach 840 billion euros by early 2022.

Ricardian equivalence may not apply. Marion Amiot, an economist at S&P Global Ratings, notes that during the region’s debt crisis about a decade ago, people cut their savings rate even as some countries raised taxes.

She also says when European officials lifted the first round of strict lockdowns last year, the savings rate of households as a percentage of disposable income fell to 17% in the third quarter from 25% in the second quarter.

“The same thing is likely to happen when things normalize this year,” she said. “There’s no evidence that this relationship exists in the euro zone.”

Outside the bloc, the Bank of England doubled its estimate on Thursday of how much U.K. residents would run down their excess savings over the next three years, to 10% from 5%.

Read My Lips

Some governments have shown they’re aware of the risk. French officials have said a post-crisis tax hike would drag on economic growth and consumer confidence. Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said last week that “we have cut taxes and we will stick to this line: no tax increases in our country.”

Spain’s administration has said it will hold off on any tax increases until the recovery is on solid footing.

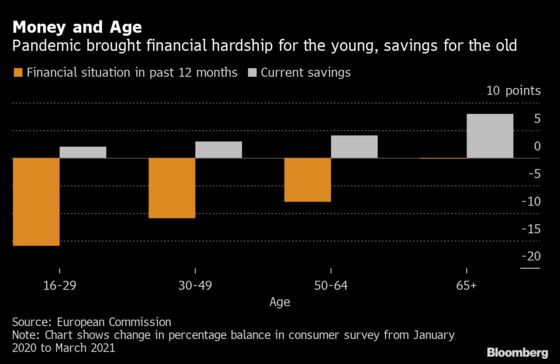

Hernandez de Cos said Ricardian equivalence is just one factor to consider. He also said some demand is lost forever -- for example, canceled vacations in 2020 won’t mean people take extra vacations in 2021 -- and savings are skewed toward richer people who tend to spend a smaller share of their wealth than low-income groups.

Still, economist Oliver Rakau at Oxford Economics reckons older, wealthier people will spend more than expected. He has analyzed consumer surveys that show higher-income households report the greatest increase in intentions to make major purchases.

He says Hernandez de Cos is probably trying to stave off any suggestion that monetary and fiscal support for the economy should be withdrawn too soon.

“Evidence of Ricardian equivalence in Europe is not necessarily very straightforward,” Rakau said. “I would tentatively interpret caution by the Bank of Spain as that they want to caution against too much optimism.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.