Messier Than Opioids, Meth Is Asia’s Worst Narcotics Threat

Unlike with opioids, there’s no approved remedy to quash cravings of meth.

(Bloomberg) -- Dale reclines in a chair and meditates while two doughnut-sized magnetic coils press against his skull. The device sends stimulating pulses into his brain to quell soul-crushing cravings that derailed his life when he got hooked on Asia’s worst narcotics threat late last year.

The health worker, who declined to be identified by his full name, enlisted for the half-hour experimental procedure in a Melbourne psychiatric clinic after a few months of using the powerful psycho-stimulant crystal methamphetamine sapped his memory, blackened his mood, and drove him to stealing needles from his employer.

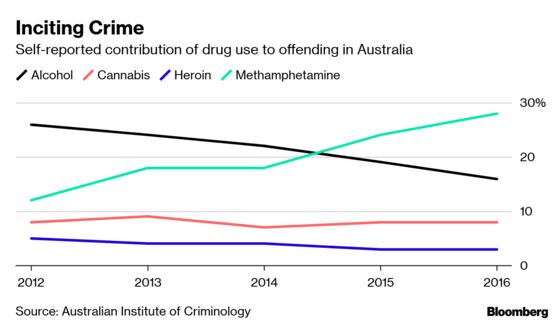

The party drug also known by the street name ice has overtaken heroin in parts of Asia and the Pacific, creating an epidemic of substance abuse reminiscent of North America’s opioid crisis -- only more disruptive. The chemical triggers a state of energized euphoria, giving addicts confidence and bravado to act on extreme impulses to murder, rob, engage in risky sex, and even in one case try mixing the stuff in a Walmart Inc. store.

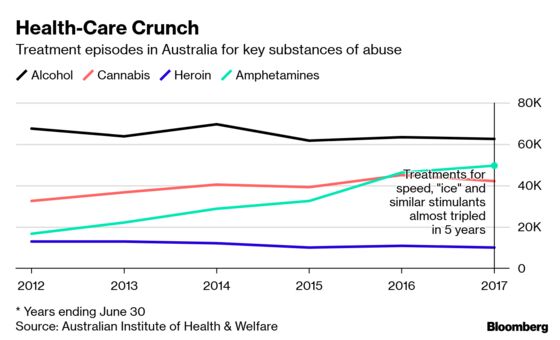

“People are very nervous about calling it a crisis, an epidemic -- but this is unprecedented,” said Rebecca McKetin, deputy director of the National Drug Research Institute in Perth, Australia. “We have a shortfall of treatment places and waiting lists.”

No Antidote

Unlike with opioids, there’s no approved remedy to quash cravings, prompting doctors to urgently look for potential treatments and experiment with what has worked for other neuropsychiatric conditions. That’s the case with transcranial magnetic stimulation, the procedure tested on Dale.

The non-invasive therapy uses magnetic pulses to activate a positive mood pathway in people with depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, and is showing promise in addiction, according to psychiatrist Ted Cassidy, chief medical officer of TMS Australia, which runs a chain of clinics that offer the procedure.

Australia’s use of crystal meth is among the highest in the world. Its harmful effects have escalated even as the government spent more than A$285 million ($200 million) to combat the scourge over the past four years.

“People are doing things under the influence of meth that they probably wouldn’t do otherwise,” said Jason White, a pharmacologist who chairs the World Health Organization’s expert committee on drug dependence. “The nature of the problem is very different” from addiction with other narcotics, he said.

Melbourne patient Dale said his constant urge to have crystal meth injected into a vein in his inner arm eased after the first few of the 20 daily TMS sessions he commenced in January.

“I was able to sit with it more comfortably and not act on it -- that was a very obvious change,” he said.

Before seeking treatment, Dale was one of about 268,000 regular methamphetamine users in Australia. Wastewater analysis shows 9.85 metric tons of the illegal substance, worth some A$7.3 billion was smoked, snorted, swallowed or injected in the country in the year through August 2018 -- a 17 percent increase on the previous 12 months.

“There’s no question, we have a big problem,” Michael Farrell, director of the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre at the University of New South Wales. His group in Sydney is coordinating a multicenter clinical trial using the key ingredient in Shire Plc’s attention deficit hyperactivity disorder drug Vyvanse in 180 heavy methamphetamine users.

The aim of the study is to test if daily capsules of the slower-acting stimulant are more effective than a placebo in reducing drug use, cravings and withdrawal symptoms over a 12-week period. The government-funded trial is due to conclude in October, with results slated for early 2020.

Other scientists are investigating the dietary supplement N-acetyl cysteine, also used to counter acetaminophen overdose, a 57-year-old muscle relaxant called baclofen, and long-acting implants of naltrexone, the medication commonly used for alcohol and opioid dependence.

Competing Circuits

But the biggest hope may lie beyond the traditional chemical approach because of the way the human brain is wired, according to Andrew Lawrence, who heads an addiction laboratory at the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Melbourne.

Anti-addiction drugs often target brain circuits involved in both abstinence and relapse, Lawrence said. That means that a drug aimed at preventing relapse might also work against the brain circuit promoting abstinence, thereby negating its benefit.

Lawrence and colleagues are studying the use of alternative approaches, including light therapy in the form of optogenetics, to discreetly manipulate the activity of a subset of brain cells to elicit specific behaviors.

Down the hall, researcher Jee Hyun Kim is looking into the biological drivers of chronic relapse, the hallmark of drug addiction, and finding that it’s “fundamentally a memory disorder,” probably with a genetic basis that is especially pernicious in the adolescent brain.

Her experiments with mice show methamphetamine is “way more addictive than cocaine or opioids,” she said.

Dale, whose cravings for crystal meth escalated within weeks of dabbling in it last October, says the drug has hijacked his life. “I’m a sadder person,” the 58-year-old said. “My personality has changed completely.”

To read more about the future of health care, subscribe here to get our Prognosis newsletter delivered to your inbox every Thursday.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jason Gale in Sydney at j.gale@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brian Bremner at bbremner@bloomberg.net, Marthe Fourcade, John Lauerman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.