Why the Gig Economy Isn't Showing Up in Data

Why the Gig Economy Isn't Showing Up in Data

(Bloomberg) -- When the U.S. Labor Department released its contingent-worker survey in 2018 following a more than 10-year hiatus, it was keenly watched by economists and journalists alike. It would be the first numerical glimpse of America’s non-traditional work arrangements since companies including Uber Technologies Inc. and Lyft Inc. burst onto the scene.

To the surprise of many onlookers, the pool of contingent workers had actually shrunk.

A dig into the numbers made it clear that the survey wasn’t well equipped to capture today’s gig work: it looked at primary jobs, not side employment, for instance. New research suggests the challenges in quantifying gig work might run even deeper -- and those findings make up the lead item in this week’s economic research roundup.

Ahead of Friday’s U.S. jobs report, we also summarize research on factors that may be holding back wage growth and on how the declining labor share of income varies across countries. Finally, we link to a Bank of England blog post on the role central banks might have to play as climate change bites. Check this column each Tuesday for new and pertinent economic studies from around the world.

Gigging It

Measuring the Gig Economy: Current Knowledge and Open Issues

Published August 2018

Available on the NBER website

From ridesharing to chores, gig work seems to be everywhere -- except showing up in the data. Theoretically, gig workers ought to classify themselves as self-employed, but the share of self-employed Americans has actually drifted lower in survey data collected since the mid-1990s.

But data from tax filings show some evidence of the uptick one might expect. Researchers including University of Maryland’s John Haltiwanger and Katharine Abraham use a newly-created dataset that links household surveys and tax-based records to clear up the discrepancy. They find that a large and growing fraction of those with self-employment activity in tax data don’t report that self-employment in household surveys. That might be happening because gig work is often secondary to a main job, and surveys aren’t well designed to probe deeply into back-up work.

The gap matters. If data fail to capture the expansion of the gig economy, “the pattern of estimated productivity growth may have been distorted,” the authors write.

Weekly Demo(graphic): Optimistic Take

Revisiting Wage Growth

Published Aug. 16

Available on the San Francisco Fed website

Wages have been slow to accelerate in the U.S. even as unemployment declines to historic lows. But the situation looks very different when researchers control for who is punching the clock.

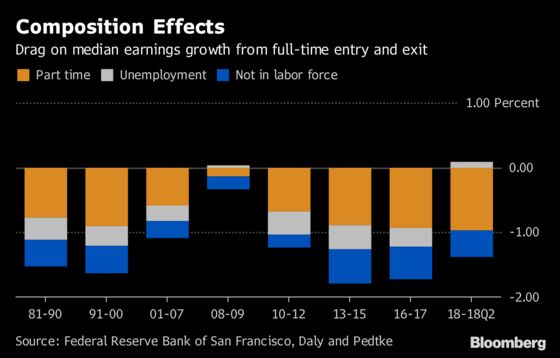

Second-quarter pay would have come in at a 3.5 percent increase when adjusted for labor force composition, much higher than the 2 percent gain that data suggest, based on research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. The logic is that high-earning baby boomers are aging out of the job market, handing the baton to comparatively cheap millennials. At the same time, people are pouring into jobs and off of the sidelines, and they tend to make less. The chart below shows how much shifts into full employment -- or from full employment to other labor statuses -- are weighing down wages.

“The bottom line is that adjusting for compositional changes matters, especially when considering whether weak wage growth is providing a signal about labor market slack,” Mary Daly and Joseph Pedtke write.

Labor Share

The Evolution of the Labor Share Across Developed Countries

Published Aug. 30

Available on the Cleveland Fed website

It’s impossible to talk about wages these days without giving a nod to labor share, which is how much national income goes to wages. While labor share has been falling across advanced economies over the past two decades, the reasons for that trend might vary by country, based on this new research by the Cleveland Fed.

In the U.S., a move from high-labor-share manufacturing to low-share services seems to have driven the change. The gap between labor shares from industry to industry is less dramatic in other advanced economies, so sectoral change was probably a less important driver. The analysis doesn’t look into what else might be causing the decline, though it mentions that reduced union participation, offshoring and demographic changes are seen as potential culprits.

Hot Policy

Climate Change and Finance: What Role for Central Banks and Financial Regulators?

Published Aug. 30

Available on Bank Underground blog

Central banks and financial regulators could help develop methodologies and modeling tools to assess climate-related financial risks, a group of European academics suggest in a post published on the Bank of England’s blog. The expectation of stricter climate policies could cause carbon-linked asset prices to shift rapidly, they note, and conventional macroeconomic models don’t easily capture such possibilities.

The international Financial Stability Board has already established a task force on climate-related financial disclosures, which has made recommendations on how companies could disclose climate-related financial risks, but the authors say there is more to be done. They even suggest that “climate-related financial risks, if deemed material, could be reflected in the collateral frameworks and the asset purchase programmes of central banks.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Randall Woods, Sarah McGregor

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.