Nafta Do-Over Distracts From the Big Trade Problem

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- If President Donald Trump’s pronouncements are to be believed, the North American Free Trade Agreement between the U.S., Canada and Mexico will soon be replaced by a bilateral U.S.-Mexico trade agreement, presumably with a U.S.-Canada agreement to follow.

The actual changes to U.S.-Mexico trade rules don’t look very substantial. The new agreement essentially implements a partial minimum wage for the Mexican auto-export industry, stipulating that at least 40 to 45 percent of the content of cars sold from Mexico into the U.S. will have to be made by workers being paid $16 an hour or more. Rules of origin for these cars have also been tightened, so that in order for a car to be sold from Mexico in the U.S., 75 percent or more of that car must have been made in either the U.S. or Mexico. Mexico also agreed to strengthen collective bargaining for workers, and slightly increase intellectual property protections for U.S. companies.

Depending on the precise implementation, these changes might end up being mostly cosmetic. If the rules of origin end up including Canada, then most Mexican car exports to the U.S. already meet the 75 percent requirement. If the $16 minimum wage applies to content made outside of the U.S. and Mexico, then it’s also likely that little will change, since workers in the U.S., Canada, Europe, Japan and other rich countries that make auto parts for cars assembled in Mexico typically earn more than $16.

In other words, the Mexico trade shakeup might be nothing more than posturing, an attempt by Trump to fulfill an earlier promise to end Nafta, or a way to gain leverage in a showdown with Canada. Or, if the rules are enforced a certain way — requiring that Mexican auto workers quadruple their wages from current levels, or requiring car companies to move auto production from Canada to Mexico — they could cause substantial economic disruption, leaving American workers and consumers worse off. Either way, Trump’s latest trade move seems like yet another unforced error.

But Trump’s focus on scrapping Nafta mirrors a wider trend in American society — a misplaced, unhealthy obsession with the 1994 trade agreement. Both the left and the right have fetishized the relatively innocuous Nafta while paying less attention to much more important trade issues — in particular, China.

Younger readers may find this hard to remember, but Nafta was incredibly controversial from the start. In 1992, third-party presidential candidate Ross Perot warned that the agreement would lead to a “giant sucking sound” as American jobs moved south to low-wage Mexico. In 1993, Vice President Al Gore staged a memorable debate with Perot — at the climactic moment, Gore produced a picture of the architects of the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariff, presented it to Perot as a gift, and warned against following a similar path.

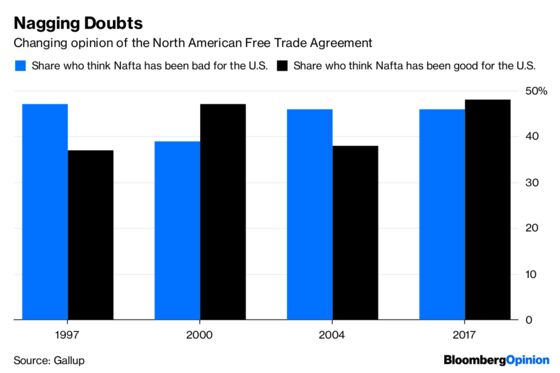

A quarter-century later, however, Americans still aren’t quite convinced:

Meanwhile, a recent YouGov poll finds that although 56 percent of Americans think international trade is good for the economy, only 30 percent are opposed to leaving Nafta.

Why does such intense anti-Nafta sentiment persist? It’s true that Nafta probably hurt some U.S. workers. A paper by economists Shushanik Hakobyan and John McLaren has found evidence that American workers in industries (mostly light manufacturing) and locations subject to increased Mexican competition suffered in the aftermath of the deal.

Although certainly painful for the workers affected, the losses weren’t huge relative to the size of the U.S. economy. Robert Scott of the Economic Policy Institute estimates that 400,000 U.S. workers were displaced from manufacturing to other industries thanks to Nafta, while the deal lowered employment by about 116,000 during the Great Recession. Those numbers are small compared to the size of the U.S. workforce. And they have to be measured against broader economic gains — a team from the Congressional Research Service estimated that the deal helped the U.S. economy grow by a total of 0.5 percent. Other economists have also found modest net gains.

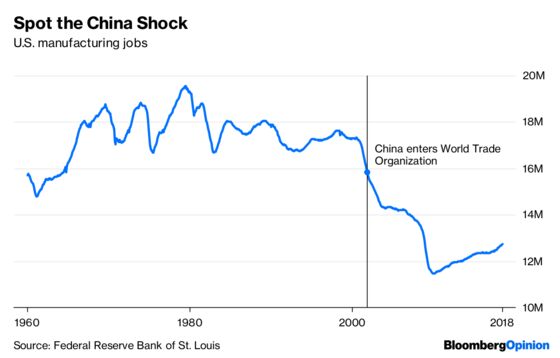

In general, therefore, Nafta hasn’t been that big a deal — certainly not in comparison to trade with China. Manufacturing employment in the U.S. held up fine in the years after Nafta was adopted, then fell off a cliff right about the time that China entered the World Trade Organization in 2001:

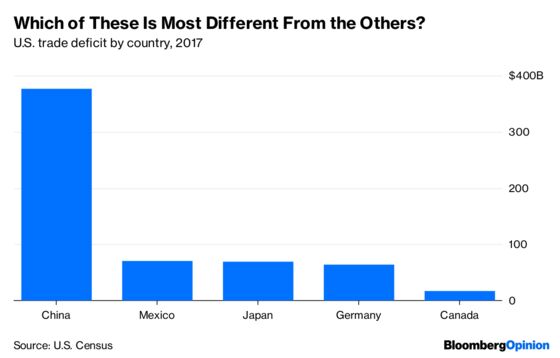

Meanwhile, the U.S. trade deficit with Mexico, though substantial, is only about one-fifth the size of the deficit with China:

It’s China, not Mexico, that should be the sole focus of any U.S. push for fair trade. In fact, by making it easier for U.S. companies to source products from Mexico instead of China, Nafta has probably slowed China’s drive to become the economic center of the world. Every U.S. dollar that goes to Mexico instead of to China helps North America retain its status as a crucial cluster of economic activity.

There’s may be one more reason that some Americans, especially conservatives, dislike Nafta — it probably raises the specter of closer political integration between Mexico and the U.S. Some have even worried that it’s the precursor to a North American union, which would presumably allow Mexicans to readily settle in the U.S.

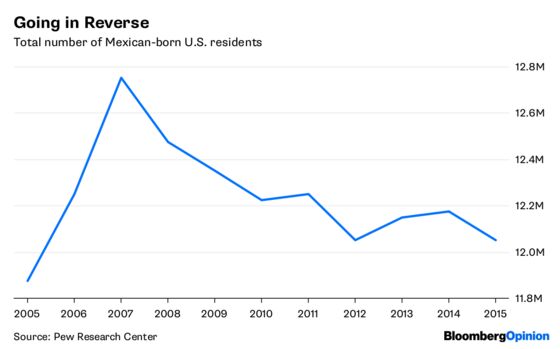

That worry is misplaced. No North American union is in the works. And Mexico’s steady economic growth is probably one big reason why net immigration from Mexico has halted and even gone into reverse:

In other words, keeping Mexico’s economy going strong, with robust U.S.-Mexico trade, is key to keeping Mexicans satisfied and happy on their side of the border. Boosting Mexico should therefore be the main objective of Trump’s trade deals with the U.S.’s southern neighbor.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.