Bank of England Tales: The Ghost, Giant and Heroic Sewer Worker

Old Lady of Threadneedle Street- as the bank is called, has built up as many stories as there are gold bars in the vault.

(Bloomberg) -- When the Bank of England’s 121st governor takes over from Mark Carney next year, he or she will be reminded that the world’s second-oldest central bank is steeped in history.

From funding wars to a buried giant and a roaming ghost, over its three centuries the institution nicknamed the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street has built up as many stories as there are gold bars in the vault.

Old Graveyard

The BOE’s first job in July 1694, when it opened its doors at rented premises in the Mercer’s Hall in the City of London, was to raise capital for William and Mary’s war against France. It then moved a couple blocks away to the Grocer’s Hall, where it fended off an upstart South Sea Company, which tried to usurp it as the government’s banker.

When that enterprise’s bubble popped in 1720, the BOE cemented its position as the home of stable money, and in 1734 moved to its legendary address on Threadneedle Street. The BOE bought the neighboring St. Christopher’s church after a group of protesters climbed the steeple during the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780 and flung missiles into the bank.

It promised to leave the graves of the church undisturbed and refurbished the graveyard as its garden court. At the end of the 18th century, the garden would once again serve to bury the dead when a giant was laid to rest.

Bank Giant

At 6 foot, 7.5 inches (202 cm), William Jenkins was a hulk at a time when the average man was 5 foot 7.

Sickly in the last weeks of his life, the bank teller developed a crippling fear that body snatchers might dig him up and sell his corpse to medical practitioners eager to inspect and display it. This was a rational fear in 1798 – the going rate for a corpse of that size was 200 guineas – about 25,000 pounds ($32,000) in today’s money.

BOE directors granted Jenkins’s friends’ request to bury him in the garden, well-guarded from grave robbers.

At this point, the bank had hired a new architect, the famed Sir John Soane. He started a massive neoclassical project that enveloped the building with an imposing curtain wall – an effective bulwark against criminals.

Ghastly Money

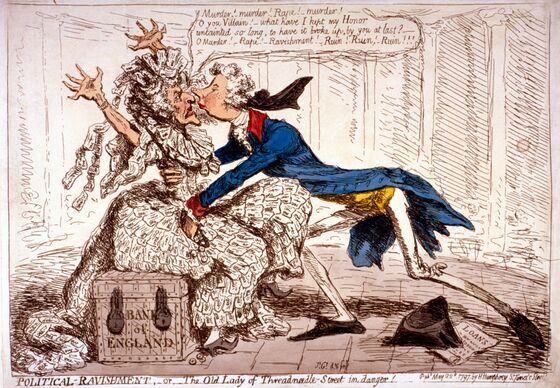

Forgery became a popular pastime in the two-decade Restriction Period as another war with France drove the government to order the BOE to stop converting banknotes into gold. That’s how the bank got its famous nickname as the Old Lady – cartoonist James Gillray portrayed it as a woman being groped by the prime minister.

With no gold coins to give, the BOE started issuing small notes, and the penalty for counterfeiting was death. More than 300 people were executed.

Some say the bank is haunted by a stubborn wraith. A clerk at the cashier’s office was indicted for faking banknotes in 1811 and later hanged. His sister Sarah found out about his demise from the BOE employees and, shaken by the revelation, continued to visit the bank wearing a black dress and a veil.

While the “Black Nun” eventually gave up after receiving a hefty compensation in exchange for a promise not to return, the legend says she still roams Threadneedle Street and the labyrinthine depths of the Bank underground station after her death.

Gold Vaults

The garden graveyard, having survived market panics and the First World War, was cleared out in 1933, when the current bank building was started by Sir Herbert Baker.

Four mulberry trees now protect the garden, reminding people of the origin of paper money. These trees are particularly suited to be BOE guardians as they spread their shallow roots horizontally without risking damage to the world’s second-largest gold vault – after the New York Federal Reserve – right below it.

About 400,000 bars of gold worth over 100 billion pounds rest safely underground on long shelves. It’s never been successfully robbed, though it’s rumored that a sewer worker in 1836 managed to sneak in through the floorboards. It’s said he was rewarded 800 pounds for exposing the vulnerability without taking advantage of it.

The BOE building is now guarded by men in top hats and pink coats with long tails. The grand halls still overlook the courtyard, a Roman mosaic adorns the basement, and the interest-rate setting Monetary Policy Committee meets in a room decorated in 18th century style. The Court Room features a link to a weather vane on the roof, a relic from when the bank would gauge the need to issue more cash by how the wind was blowing as merchant ships sailed into London.

There’s still history to be made at the bank. While Carney, a Canadian, became the first foreigner to run the BOE, his successor could be the first female chief, giving the 324-year old institution a chance to finally live up to its nickname.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brian Swint at bswint@bloomberg.net, Paul Gordon

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.