Turkey Was Ripe for a Currency Crisis. Will It Spread?

The country’s plight sparks fears of an emerging-markets meltdown.

(Bloomberg Businessweek) -- The hurt that President Trump laid on Turkey on Aug. 10 was feather-light— a doubling of tariffs on imported Turkish steel and aluminum. Turkey sells only about $1.4 billion in primary metals to the U.S. in an average year, according to the U.S. Commerce Department. So the new levies will reduce the country’s gross domestic product by just about 0.04 percent. And that’s assuming Turkish mills and smelters have to cut prices by 25 percent to retain their American customers—the hit will be even less if the Turks find customers in other nations that aren’t jamming it with high tariffs.

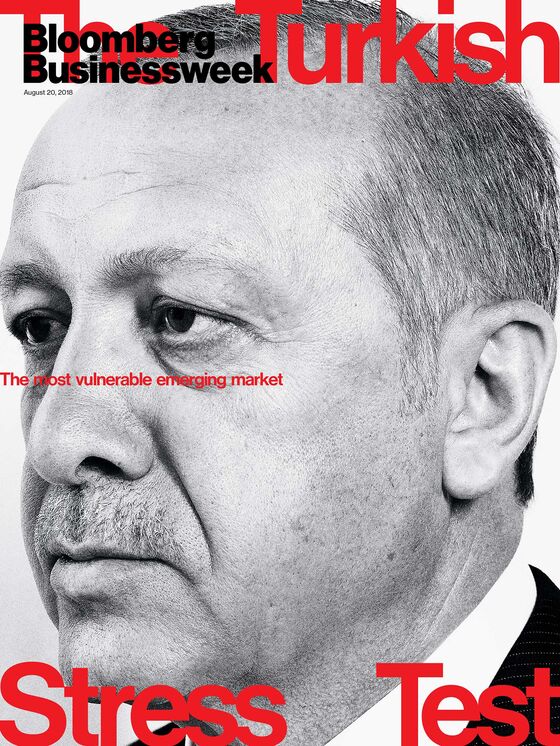

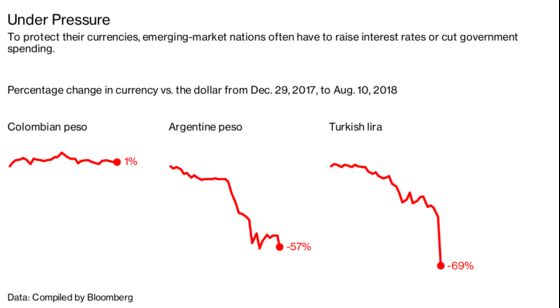

So why did a 0.04 percent slap on the wrist—more of a tap, really—cause the Turkish lira to plummet; prompt President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to complain of “economic warfare”; push down the currencies of Argentina, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Russia, South Africa, and Zambia; and raise Italy’s borrowing costs to their highest vs. Germany’s since May? It’s simple, actually. Conditions for a crisis were ripe. Financial weakness and poor policies in Turkey and other vulnerable nations supplied dry tinder. Two headstrong characters, Erdogan and Trump, butting heads like flint and steel, provided the spark. “Countries go through stress in two ways, gradually and then suddenly. We’re seeing the ‘suddenly’ right now,” says Samy Muaddi, a Baltimore-based money manager at T. Rowe Price Group who manages the Emerging Markets Corporate Bond Fund.

The currency crisis is a huge blow to Erdogan, who won reelection in June. Investors grew restive after the vote when he appointed his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, as treasury and finance minister and exerted pressure on the central bank not to raise interest rates, which would have helped defend the currency and lower inflation. Now things are coming to a head. Turkish banks and nonfinancial businesses borrowed heavily in dollars, so the fall of the lira will sharply increase their financing costs, raising the risk that this becomes a full-blown debt crisis. “The authorities need to act decisively, but history suggests that they will instead procrastinate,” writes Nafez Zouk, the lead emerging-markets economist at Oxford Economics in London.

Erdogan has been wanton in his management of the economy. He suggests that high interest rates are “the mother and father of all evil” and subscribes to a theory that increasing them causes inflation. In striving to show financial independence, the autocrat has done the opposite: raised the likelihood Turkey will eventually require assistance from the International Monetary Fund, China, or someone else. On Aug. 14 he was reduced to threatening a boycott of iPhones. The next day, Qatar threw him a lifeline, promising to invest $15 billion in Turkey. The strongman appears weak.

For the rest of the world, the risk is contagion, the transmission of financial problems from one nation to another. Even if Turkey doesn’t directly infect other countries, its troubles could instigate a general retreat from vulnerable emerging markets. Contagion “is a very elusive term,” says Lale Akoner, a market strategist for BNY Mellon Investment Management in New York.

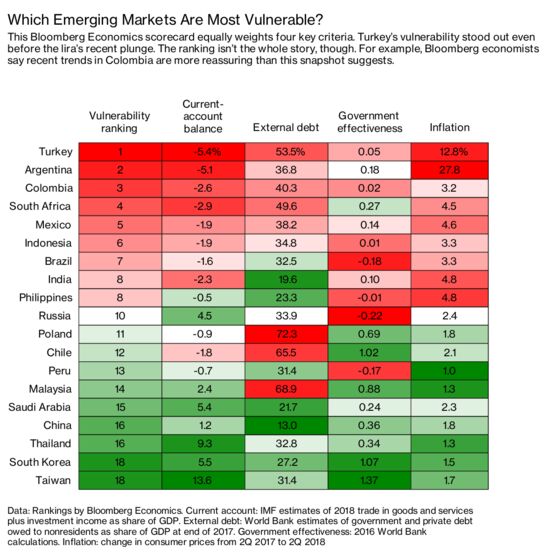

To be sure, contagion is not what most economists are predicting, given that Turkey accounts for only 1 percent of the global economy and the market value of all Turkish companies traded on the Istanbul Stock Exchange is less than that of McDonald’s Corp. The Turkey-centered crisis is likely to be milder than the emerging-markets crisis of 1997-98, which began when Thailand abandoned its peg of the baht to the dollar. That episode slammed Indonesia and South Korea as well as Thailand. It also touched Hong Kong, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Since then, Asian economies have fixed their finances and built reserves of foreign currencies as cushions against a panic. The fallout this time might even turn out to be less than after the “taper tantrum” of 2013, when countries such as India, Indonesia, Mexico, and Poland were infected by fear that the Federal Reserve was about to taper its purchases of long-term bonds, driving up U.S. interest rates and sucking money away from emerging markets.

But the crisis is still ugly for nations that are under pressure—particularly Turkey itself, whose inflation rate, 16 percent in July, will go even higher when the drop in the value of the lira raises import prices. (The lira is down almost 40 percent this year.) And the crisis is affecting leaders of countries who, unlike Erdogan, are trying to hew to economic orthodoxy. In South Africa, the rand’s decline puts pressure on President Cyril Ramaphosa, who took office in February on a promise to end corruption and stagnation. Likewise, in Argentina, a declining currency and rising bond yields complicate the job of President Mauricio Macri, whose market-friendly economic policies are a contrast to those of his predecessor, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

Two lessons emerge from this episode. The first is that if you’re in a small country with an economy that’s open to foreign trade and investment, you should borrow cautiously. And resist the temptation to borrow in foreign currencies to qualify for a slightly lower interest rate. The Institute for International Finance estimates that dollar-denominated corporate liabilities total $3.7 trillion in emerging markets, double the amount of 2010.

The point is, you don’t want to put yourself in a position where you depend on the kindness of strangers, especially if those strangers are people who manage billions of dollars in investments on the trading desks of New York and London. They will lavish money on you when times are good, taking advantage of the higher returns typically available in emerging and developing markets. But when the good times go bad, they will turn against you in a heartbeat, driving down the value of your currency, raising your borrowing costs, and pulling out their hot-money investments. There’s no sentiment on a trading desk.

South Korea learned this lesson, if anything, too well. Once a borrower, it’s become one of the world’s biggest savers since it got a scare during the Asian financial crisis. The country has a surplus on its current account—the broadest measure of trade in goods and services and investment income—equal to 5 percent of GDP. The problem with so much saving is that South Korea, like Germany, isn’t buying its fair share of the world’s goods and services. Instead, it’s keeping its own citizens employed in the export sector.

Turkey is at the opposite end of the spectrum from South Korea. In this year’s first quarter it ran a current-account deficit equal to 6.3 percent of GDP. That trade balance measure has been in the red every quarter but one since the end of 2002. In other words, Turkey has been borrowing and spending beyond its means, running up a tab that’s now coming due.

Bloomberg Economics rates Turkey the most vulnerable of 19 emerging-market economies based on four equally weighted criteria: the current-account balance, external debt as a share of GDP, government effectiveness, and inflation. “No other country has quite the same combination of weak and deteriorating fundamentals, as well as a government sprinting away from economic orthodoxy,” writes Tom Orlik, chief economist of Bloomberg Economics. The next four most vulnerable among the big emerging-market nations are Argentina, Colombia, South Africa, and Mexico.

The second lesson from this minicrisis is that U.S. behavior continues to matter. As bad as Erdogan’s leadership has been, it took a Trump tweet to turn very bad into disastrous for Turkey. The lira fell 18 percent the day of his tariff announcement. The tweet was something of a gift to Erdogan, because it added weight to his claim that Turkey was the victim of hostile outside forces.

Trump’s tweet rattled markets because U.S. presidents have sought to calm market turmoil in the past, whereas Trump intensified it. What’s more, his justification for the tariffs was both murky and disconcerting. Many investors assumed the tariffs were intended to add pressure on Erdogan to release an American evangelical pastor, Andrew Brunson, from house arrest, since Trump had just finished sanctioning two Turkish government ministers over the affair. Other investors speculated that the tariffs were intended to offset the pricing advantage Turkey was getting from a cheaper currency, because in his tweet, Trump noted that “their currency, the Turkish Lira, slides rapidly downward against our very strong Dollar!” Either of those justifications could run afoul of the World Trade Organization, of which the U.S. is a founding member. Twelve hours after the tweet, the White House stated, somewhat implausibly, that the real reason for the tariffs was to boost national security by protecting U.S. steel and aluminum producers—without explaining why they had been applied only to Turkey and not bigger sources of metal imports.

The American who has the most sway over emerging markets may not be Trump but Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. The Fed is raising interest rates to prevent inflationary overheating in the U.S. That pushes up interest rates all over the world, as companies and governments compete for limited funds. On May 8, Powell said that the Fed wasn’t primarily responsible for global flows of capital and that emerging markets were well-positioned to navigate the U.S. rate hikes. Still, if an emerging-markets crisis gets bad enough, Powell’s Fed could dial back on rate hikes on the grounds that it may curtail U.S. growth.

Turkey is likely to remain a thorn in the paw of the world economy for some time to come. That’s because, of the two lessons of this crisis, Erdogan is ignoring the first one, about the need for sound economic management, and Trump is ignoring the second, about prudent U.S. leadership. The two heads of state, who as recently as July appeared to be best buddies, are at loggerheads. It looks like a replay of Trump’s relationship with Chinese President Xi Jinping, another authoritarian whom Trump both admires and is infuriated by.

Contagion, if it occurs, could happen through defaults that damage banks in lending nations. Spain’s Banca Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, Italy’s UniCredit, and France’s BNP Paribas are the most exposed lenders, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. But those banks, and certainly their host nations, should be able to ride out loan losses. Shares of BBVA, the worst off, are down 12 percent this month and 24 percent so far this year.

More vulnerable are Turkey’s fellow debtor nations. Contagion can occur mechanically when investors lighten up positions in, say, Argentina or South Africa to compensate for losses on Turkey, keeping their overall emerging-market risk below some predetermined threshold. Or it can occur if Turkey becomes a “wake-up call” that leads investors to take a closer look at other nations’ fundamentals and find them wanting, says Akoner of BNY Mellon.

And things could get worse from here. “Our big worry is if Turkey really goes into a major, major crisis, and they impose capital controls,” preventing investors from getting their money out, Paul McNamara, a London-based fund manager at GAM UK Ltd., told Bloomberg Television. “That’s the sort of thing that brings the asset class into sort of disrepute.”

If prices go down too far, though, bottom-fishers will surely emerge, as they always do. The volatility set off by Turkey is “replete with opportunity,” Jan Dehn, head of research at Ashmore Group PLC in London, wrote to clients on Aug. 13. Turkey’s problem is “entirely self-inflicted, and it will not suddenly appear in, say, Poland or Uruguay,” he added.

Dehn’s approach echoes the Wall Street adage that the best time to invest is when there’s blood in the streets. Exciting advice unless you’re an ordinary Turkish citizen and the blood in the streets is your life savings. —With Enda Curran and Michelle Jamrisko

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Howard Chua-Eoan at hchuaeoan@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.