Fed Mines Big Data for Real-Time Clues on Spending and Payrolls

Federal Reserve officials deploy an experimental new tool for real-time answers on spending.

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve officials deployed an experimental new tool as they scrambled to assess the harm done by storms hammering the U.S. last year: a trove of big data that gave them real-time answers on spending they’d normally have to wait on for weeks.

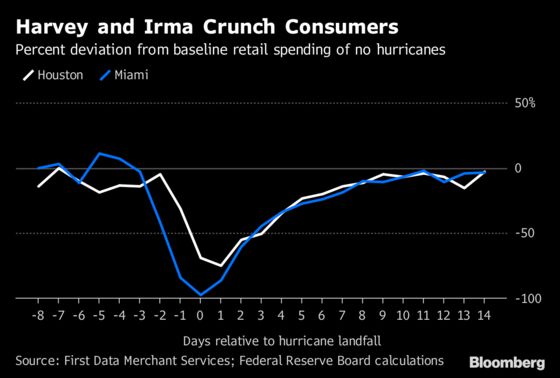

Instead of guesswork and monthly retail sales readings, they used card swipe information from First Data Corp., a global payment technology company, to get a picture within three days of what hurricanes Harvey and Irma had done to the economies of Houston and Miami.

It wasn’t a pretty sight.

Spending at stores and restaurants in Miami and Tampa dried up almost completely, while in Houston the decline was 75 percent from normal spending levels. Two weeks later the data also showed there’d been no big above-normal rebound. That information helped the Fed gauge how much weather disruptions would detract from third-quarter economic growth, a message reflected in the Federal Open Market Committee’s policy statement on Sept. 20.

For Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, having real-time monitors on the U.S. economy’s vital signs has never been more important. U.S. central bankers are gradually raising borrowing costs to keep the economy on track, but they have only fuzzy estimates on what level of interest rates might constrain growth. Better and more timely data can yield early signals on whether policy is too loose or tight, helping the Fed avoid a potentially costly mistake.

As economic activity has become ever-more digitized, researchers have combed through private data for signals on the real economy that would give them a jump on official government reports that are released with a lag.

It’s been a challenging journey. Finding economic clues in piles of unfiltered information can be tantamount to rummaging through a city garbage dump to determine what an entire nation is spending.

Skewed Samples

Unlike government statistics, private-sector data sets aren’t gathered with a question in mind, such as, how much did the U.S. export last month? The samples can be skewed. Not all Americans pay for goods and services with swipe cards, for example, and even less so during hurricane-induced power outages when cash may be a better medium of exchange. Not all businesses use automated payroll systems. The consistency of the data can change as private-sector sources shift strategy. Privacy issues abound, and data sets must be anonymized.

One reason government agencies are paying more attention, however, is the tools to analyze the information are improving, said Brian Moyer, director of the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“What has really changed is not so much the availability of the data, but the data science tools and our ability to process and use it in real time,” Moyer said in an interview, adding that BEA is trying to enhance the accuracy of government reports, not replace them with private data sets. “We can drill into the changing composition of goods and services expenditures and that is what is going to keep GDP accurate.”

Multiple Experiments

Jeff Chen, chief innovation officer at BEA, said the agency is experimenting with hundreds of different prediction models that use public and private data, such as Google search queries, to come up with better estimates for service expenditures. BEA is also looking at Zillow Group Inc. real estate data to sharpen its estimates of housing consumption.

It’s a critical endeavor. The BEA’s advance estimate on GDP is released before the completion of the Census’s Quarterly Services Survey so they have to impute service sector consumption.

“What big data can do is mimic what the trends will be,” Chen says. It’s computationally intensive. Refining prediction models is iterative, Chen notes, involving thousands of experiments.

Fed officials have worked along three lines of inquiry -- retail spending, employment and prices. The first two have been the most fruitful. The goal is to get timely and possibly more accurate information in front of policy makers.

Better Read

To get a sense of how useful this endeavor can be, consider that Bureau of Labor Statistics revisions for March 2009 total nonfarm employment was 902,000 below their estimate. Having that information sooner, in a year when unemployment hit 10 percent, could have been influential on monetary policy.

Fed staff is currently working with payroll information from Automated Data Processing Inc., which represents about one fifth of the U.S. private sector workforce. Released a few days before the closely scrutinized monthly U.S. employment report, the data have the potential to offer an advance peek at what to expect from the BLS. But for years, it’s confounded analysts who’ve tried to use it to build a reliable proxy for the employment report.

ADP’s employment number represents a different slice of the labor market than the BLS data, so the reports vary. For July, ADP’s national employment report estimated a gain of 219,000 jobs. The BLS reported 157,000.

“Both reports are different representations of the same reality,” said Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics Inc. in West Chester, Pennsylvania, which consults with ADP on the project. The BLS estimate is based on payroll records of millions of workers, “and so too is the ADP estimate, just a different set of workers.”

Fed officials aren’t trying to guess monthly payrolls. They’re looking at both ADP and the BLS data and using statistical methods to try capture the message from both reports about true employment.

“We are not about accumulating the biggest data repository in the world for its own sake,” said David Wilcox, the director of the division of research and statistics at the Fed Board of Governors in Washington. “Instead, our objective is to advance our ability to advise monetary policy makers.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Craig Torres in Washington at ctorres3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alister Bull at abull7@bloomberg.net, Jeff Kearns

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.