Why the Bank of England Will Probably Raise Rates, and Why It Might Not

There are still plenty of reasons why BoE Governor Mark Carney and his colleagues might hold rates steady.

(Bloomberg) -- There are still plenty of reasons why Bank of England Governor Mark Carney and his colleagues might hold fire on an interest-rate increase this week.

Investors are betting there’s a 90 percent chance of a quarter-point hike to 0.75 percent on Thursday, which would be only the second increase since the financial crisis. That’s despite Brexit weighing on the U.K., and the economy is already lagging behind its peers.

“This isn’t a done deal,” said Dean Turner, U.K. economist at UBS Wealth Management.

Here are the reasons for and against.

The Data Say Go

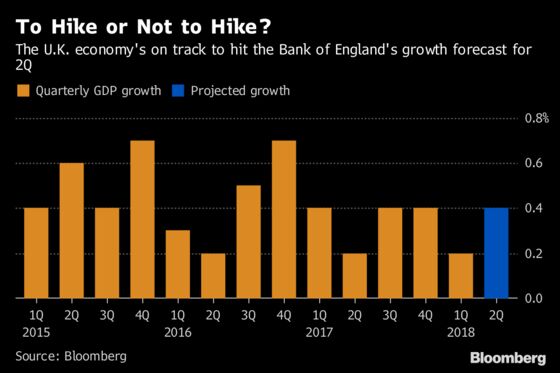

In May, policy makers said that rates will need to go up a few times over the next three years to keep a lid on inflation if the economy performs as expected. Since then, the data have shown that growth picked up after a first-quarter slowdown.

Retail sales bounced back after a snow-blighted start to the year, employment is growing and the jobless rate has dropped to about 4 percent, the lowest since the 1970s. The bank’s growth forecast of 0.4 percent for the second quarter looks achievable.

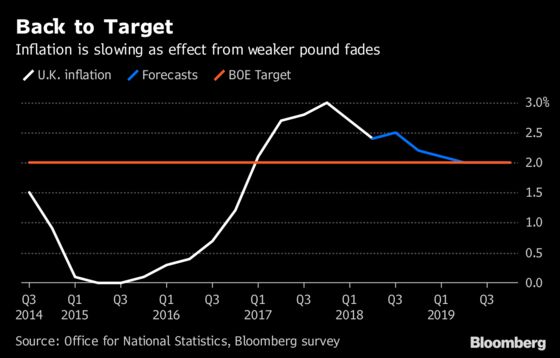

At the same time, oil prices are up and the pound is back near a 10-month low, both of which will push inflation higher.

Read more: For the BOE, August is a case of carpe diem

If Not Now, When?

Timing is key. Consumer-price growth is currently running at 2.4 percent, above the BOE’s 2 percent target, but it may not be there for long. Economists forecast it will be back at the goal by early next year, which could make selling a hike harder.

There’s also the argument that the BOE needs to get moving to get rates up before the next downturn if it wants to have decent space for cuts when they’re next needed.

Spending Splurge

Ultra-low interest rates since the financial crisis may be encouraging Britons to live beyond their means. Spending exceeded incomes in 2017 for the first time in three decades, a report last week showed.

“If there’s one thing that tips the balance it should be that,” said Andrew Sentance, a former BOE policy maker and currently an adviser at PwC. “Keeping interest rates the same isn’t the same as having neutral policy. If you keep going down that path you’ll hit a recession at some point.”

Brexit

On the other hand, the prospect of a disorderly exit from the European Union could be a reason to hold off. The U.K. is set to leave in March and it’s not yet clear what the future relationship will be like. If things go wrong, the BOE could quickly revert to crisis-fighting mode.

Carney himself said this month that having no deal in place could present a “financial stability event” for both Britain and the EU and the bank is preparing contingency measures.

Read more: How Mark Carney is preparing for Brexit

Going Ballistic

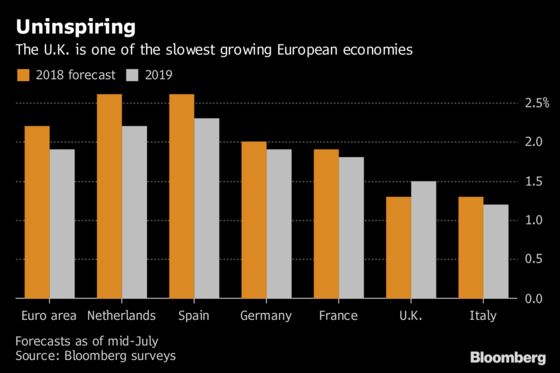

For some, the growth background isn’t strong enough to withstand tighter policy. While the BOE argues that Brexit has reduced the supply capacity of the economy, meaning that domestic inflation will ramp up even at weaker rates of expansion, Britain is still an underperformer in Europe. Along with Italy, it will have the slowest growth of any EU country this year.

David Blanchflower, who sat on the BOE’s rate-setting committee from 2006 to 2009, said he’d go “ballistic” if rates are raised. “There’s no evidence of any kind -- no data, nothing -- to support it whatsoever.”

A marked pick-up in headline wage growth remains elusive and an anticipated acceleration in annual price gains failed to materialize in June. Stripping away external influences, domestic inflation is actually slowing toward its weakest rate since 2009.

Trade Wars

The tariff battle that the U.S. has initiated with both China and the EU has dominated the outlook for much of this year, and a full-blown trade war has implications for both growth and inflation.

For Sentance, that prospect shouldn’t be a major factor in the MPC’s decision because “there’ll always be something to worry about.”

Blanchflower, who has long been on the more dovish side of debates with Sentance, disagrees. The risk of escalating tariffs is a major threat to the economy and should be reason enough to wait on a rate move, he said.

Housing Slump

The U.K. housing market, which has traditionally underpinned consumption, is weakening after a three-decade boom. Asking prices fell for the first time in seven months, Rightmove Plc reported this month, and London in particular has been hit hard.

History

There are plenty of examples of premature rate hikes in central banking history, most recently when the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2011 as the economy slid into recession. Economists at BofA Merrill Lynch, HSBC Holdings Plc and UBS Group AG have said there’s a chance that a BOE move now will look like a mistake in hindsight.

“The massive uncertainty -- mostly downside risk -- of Brexit makes it possible that they raise today and cut in November,” Willem Buiter, special economic adviser at Citigroup and former BOE policy maker, said in a Bloomberg Television interview. “That would look a bit silly.”

--With assistance from Jill Ward, Lucy Meakin and David Goodman.

To contact the reporter on this story: Elizabeth Burden in London at eburden6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, Brian Swint, Fergal O'Brien

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.