Britain’s Trickiest Economic Challenge Is Back in the Spotlight

Weak productivity has plagued U.K. since financial crisis, sapping its underlying strength, undermining wage growth.

(Bloomberg) -- Eclipsed by Brexit headlines, the most puzzling economic problem facing Britain is back in the limelight.

Abysmal productivity growth has plagued the U.K. for a decade, sapping its underlying strength and undermining wage growth. Countless explanations and solutions have been proffered, and now the debate is raging again after a proposal that fixing it be made one of the Bank of England’s core tasks.

The seriousness of the issue was laid out in stark terms by BOE Chief Economist Andy Haldane last week. “The U.K. faces perhaps no greater challenge, economically and socially, than its productivity challenge,” he said in a speech analyzing causes and solutions.

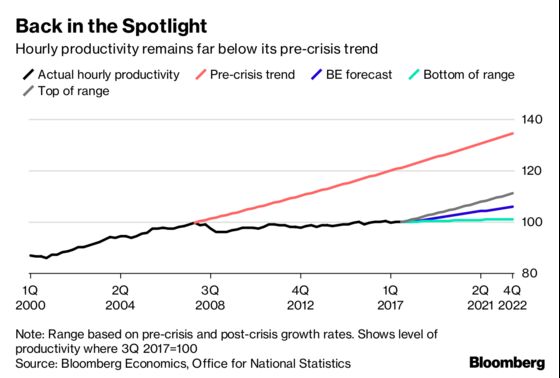

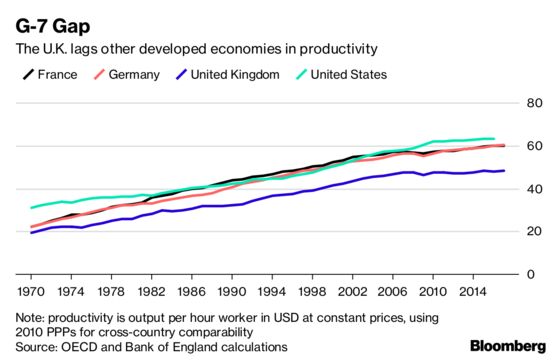

To put it in an international context, it takes a British worker five days to produce what a French worker produces in less than four. Growth in output per hour has yet to recover its pre-crisis trend and many economists fear that leaving the European Union could see Britain fall further behind by depriving the economy of productivity-enhancing foreign innovation and investment.

Any government would welcome a boost to productivity, not least because the problem is projected to cost the Treasury tens of billions of pounds in lost revenue over the coming years.

There are implications for monetary policy too. The U.K. economy is growing around 1.5 percent a year, behind the euro area and the U.S., but weak productivity growth means there is little, if any, room to expand more quickly without fueling unwanted inflation. A survey published Monday showed subdued manufacturing output, with firms flagging increased input costs and raw material shortages that add to the gloomy outlook.

BOE Governor Mark Carney has a chance to address the issue of productivity this week when he delivers a speech in Newcastle in Northern England.

Recent governments have given several nods to fixes, but some lawmakers are looking elsewhere. In a report by economist Graham Turner, the opposition Labour Party suggested that the BOE add a 3 percent productivity growth target to its remit as part of an overhaul of the monetary policy framework.

The proposal has been criticized by economists including Haldane, who argues that the supply side of the economy is not for central banks to determine.

“Central bank tools are cyclical, rather than structural,” he said in a speech on productivity on Thursday. “We do not build schools, colleges, houses, roads, railways or banks. Nor do we finance them. Those tools, rightly, are in the hands either of governments or private companies.”

A related issue is whether it’s right to hand more power to a technocratic institution already in focus for the scope of its reach and criticized for the side effects of its actions since the financial crisis.

“It’s good to be ambitious but there’s a bigger question about whether you want to give the BOE ever more powers without any more accountability,” said Torsten Bell, director of the Resolution Foundation, a London-based think tank.

The problem is, of course, not unique to Britain. Productivity has grown slowly everywhere since the financial crisis, holding back wage growth.

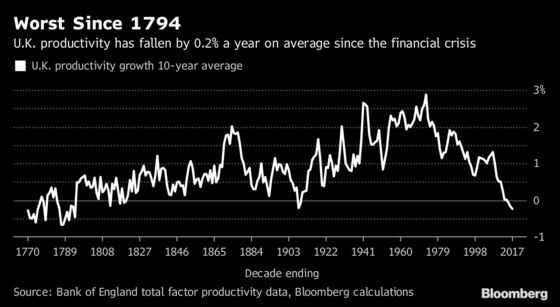

Britain nonetheless stands out. In the decade before the 2008 recession, productivity grew by about 2 percent a year. Since the recovery began, it’s averaged less than 0.2 percent, with only a minimal improvement expected in the coming years. According to a BOE analysis, worker efficiency on a 10-year rolling basis is at its lowest since the industrial revolution.

One first step may be to figure out exactly what’s happened. Diagnoses range from the drag of “zombie firms” kept alive by loose monetary policy to the U.K.’s reliance on services, which lag manufacturing in terms of efficiency growth. According to Haldane, the worst-performing quarter of British companies have levels of productivity around 80 percent or more below the median, meaning a “long and lengthening tail of stationary companies.”

Proposed remedies include sharing technology to track supply chains to making better use of universities, companies and government agencies to help transfer know-how between firms, sectors and regions.

At the BOE, the rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee is about to get a new expert on the topic. Jonathan Haskel, who joins in September, struck an optimistic tone when he testified to lawmakers last week. He argued that hard-to-measure investment in “intangible” assets such as software and design have the potential to deliver significant productivity gains in the longer term.

Haskel says central banks can aid productivity by creating investment friendly monetary conditions. But for Turner, Britain has an “entrenched” problem that highlights the limitations of the BOE’s inflation-fighting remit.

“Time and time again, it has been shown that one inflation target does not suffice to deliver prosperity,” he said in an open letter to Bloomberg. “The status quo didn’t serve us well before the 2007/08 housing crisis. It certainly won’t help as we navigate Brexit and rapid global innovation, which threatens to leave the U.K. trailing well and truly behind.”

--With assistance from Lucy Meakin and David Goodman.

To contact the reporter on this story: Jill Ward in London at jward98@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Andrew Atkinson

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.