Russia Ringfenced as Old Empire's Currencies Thrive

Russia Ringfenced as Old Empire's Currencies Thrive

(Bloomberg) -- The former Soviet republics have rarely been more free of Russia since reclaiming independence almost three decades ago.

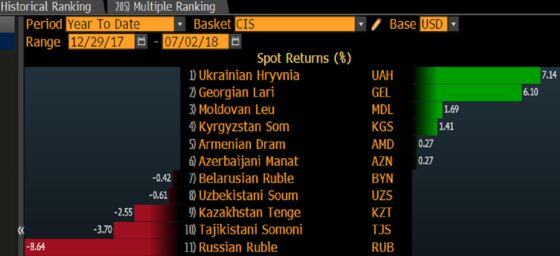

For the first time in half a decade, the Russian currency suffered the worst performance in the first six months of the year among its 11 ex-Soviet peers. After the toll taken by sanctions and tightening U.S. monetary policy, the ruble is now down over 8 percent against the dollar in 2018, more than double the loss of any other currency in the group. Without the U.S. penalties imposed in April, it would have been as much as 4 percent stronger, according to the Bank of Russia.

While the region hasn’t been immune to a broader retreat from emerging markets, Russia is increasingly taking the brunt of the downturn in sentiment. By contrast, four ex-Soviet currencies are notching gains that place them in the top 10 performers globally so far this year. Still closely intertwined with Russia through capital flows and migration, the former satellites have the advantage as they steer clear of their larger neighbor’s costly geopolitical games.

Given the fallout from Russia, several regional upstarts now warrant a second look. At meetings with investors, only about half the time is spent on Russia and the rest on the Commonwealth of Independent States, a loose grouping of former Soviet republics, according to Oleg Kouzmin, an economist at Renaissance Capital in Moscow.

Countries such as Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan or Azerbaijan “may benefit from diversification away from Russia in the near term,” said Per Hammarlund, chief emerging-market strategist at SEB in Stockholm. “But for them to really take off, they would need regime change and a government intent on rooting out corruption, strengthening state institutions, and liberalizing the economies.”

For now, the aura of risk hanging over Russia has turned its erstwhile satellites into relatively safer destinations, even though their markets pale in size compared with Russia’s. And in the case of Kazakhstan and Belarus, all members of a customs union which count Russia as the top trading partner, their currencies didn’t come through unscathed after the latest round of U.S. sanctions.

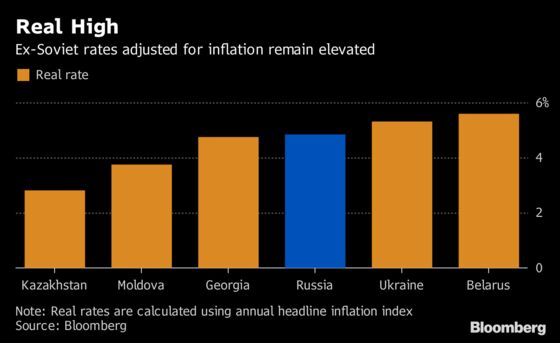

But as more central banks in the region followed Russia’s lead and allowed the market to determine the exchange rate, the correlation with the ruble has grown weaker. Elevated borrowing costs have also helped shield local currencies, with Ukraine and Belarus having higher real interest rates than in Russia.

Central banks across the former Soviet Union allow different degrees of currency flexibility, usually reserving the right to step in to smooth out sharp fluctuations. While the Bank of Russia has pledged to avoid interventions unless the ruble’s swings threaten financial stability, foreign-currency purchases by the Finance Ministry have contributed to the currency’s weakness.

Interviews with policy makers painted a mixed picture of the outlook for regional economies as Russia remains sidelined.

Kazakhstan sees an opportunity should sanctions on Russia give it an edge in attracting investors, according to central bank Governor Daniyar Akishev. “In these circumstances, Kazakhstan could and should use such competitive advantages,” he said.

For Kyrgyzstan, a central Asian nation that’s also a member of the economic bloc with Russia, the damage far outweighs any benefits, especially considering its reliance on remittances from migrants working in Russia, said its central bank Governor Tolkunbek Abdygulov.

It’s a view largely shared by Belarus. Any benefits are likely to be short-term, with Belarus possibly seeing some capital flows diverted its way, but “the minuses and risks could be rather uncertain,” Deputy Governor Sergei Kalechits said.

‘Closely Linked’

“Partly, the economies of neighboring countries could in some ways win from sanctions against Russia,” Kalechits said. “Overall the negative effects are still very serious, because the economies remain closely linked.”

As the nations have grown apart and interests diverged, former Soviet states are also piquing interest for other reasons. After more than two decades of Uzbekistan’s isolation, rapid-fire reforms have followed the death of its long-time ruler in 2016. Uzbekistan is planning to follow in Tajikistan’s footsteps and offer its debut Eurobonds this year.

Meanwhile, Kazakhstan is giving international investors access to its local-currency sovereign debt market by working with the world’s biggest bond-clearing systems.

“The chances that Kazakhstan will develop further and draw more interest from Western investors are very high,” said Sergey Dergachev, a portfolio manager helping oversee about $14 billion in assets at Union Investment Privatfonds. “Apart from Kazakhstan, I do think other markets will very gradually rise in terms of debt exposure.”

--With assistance from Evgenia Pismennaya, Nariman Gizitdinov and Anna Andrianova.

To contact the reporters on this story: Andrey Biryukov in Moscow at abiryukov5@bloomberg.net;Olga Tanas in Moscow at otanas@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Gregory L. White at gwhite64@bloomberg.net, Paul Abelsky, Alex Nicholson

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.