Powell Showcases Just How Unsure Fed Is About Policy Cornerstone

Powell and his colleagues at the Fed are especially stumped on where unemployment can settle in the long run.

(Bloomberg) -- Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell doesn’t claim to have all of the answers, but when it comes to where unemployment can settle in the long run, he and his colleagues are especially stumped.

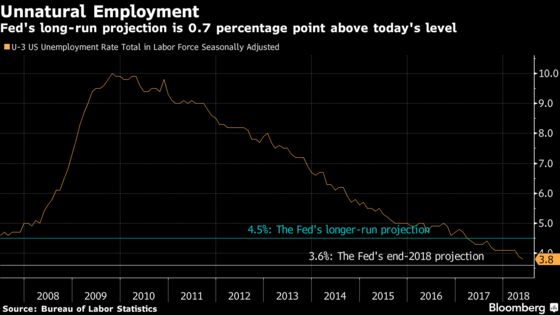

“No one really knows with certainty what the level of the natural rate of unemployment is,” Powell told reporters Wednesday after raising interest rates for the second time this year. Later, pressed about whether the Fed’s long-run estimate, now at 4.5 percent, could come down, he indicated that it’s possible. “We can’t be too attached to these unobservable variables.”

It’s a crucial uncertainty, because the natural jobless rate is a linchpin of Fed policy. It’s a signal of how hot Fed officials think the job market is running, which in turn tells them how much inflation is brewing relative to their 2 percent target and how aggressively they need to raise rates to maintain an even keel.

Unemployment estimates have been a question mark for some time -- the U.S. central bank has lowered the long-run estimate by about a percentage point over the past 5 years -- but the stakes are now higher.

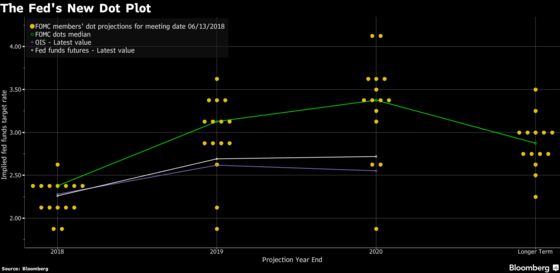

The Fed is gradually raising rates and will soon reach what officials think is the neutral level, the policy setting that neither stokes nor slows growth. If they push past that and the job market isn’t overheating, it could needlessly choke off growth and tamp down inflation.

If, on the other hand, the labor market is galloping past potential, their slow pace might risk inflation taking off.

“The fact that we live in that uncertainty is why we’ve been gradually raising rates,” Powell said Wednesday. “We’re not waiting for inflation to show up, we’re -- we’re going ahead and moving gradually and trying to navigate between two risks really.”

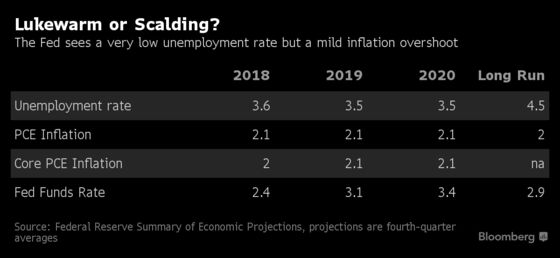

Unemployment was 3.8 percent in May, and the Fed sees it falling to 3.6 percent by the end of the year and dipping to 3.5 percent in 2019 and 2020. That would be the lowest level since the 1960s.

Officials left their estimate of the longer-run natural rate at 4.5 percent on Wednesday, suggesting that they see a job market that’s running warm.

Despite that, wages have been moving up gradually -- not taking off -- and inflation has been close to or below the Fed’s 2 percent goal. The Fed seems to think price pressures will remain contained: They forecast a small overshoot on inflation, but they don’t see it climbing above 2.1 percent over the next three years, according to their median estimates.

“There’s no sense that inflation will -- no sense in our models or in our projections or forecasts that inflation will take off or move unexpectedly quickly from these levels, even if unemployment does remain low,” Powell said. “If we thought that inflation were going to take off, obviously we’d be showing higher rates. But that’s not what we think will happen.”

It could be that Fed officials only move that long-run rate gradually over time, while they’re more actively moving the short-run estimates to keep pace with incoming economic data.

Slow-Moving Variable

“We don’t think that the natural rate of unemployment -- it’s not one of those variables that moves around a lot,” Powell said Wednesday. Still, he indicated that there are reasons for its continued decline.

“It tends to be driven by slow-moving variables like the education level of the population,” he said. “Is it on a cyclical basis lower as the economy gets hotter and hotter? There’s some possibility of that.”

Powell has previously indicated that the natural jobless rate might be lower. In early March, the Fed chief told Senators that unemployment -- then at 4.1 percent -- was “at or near or even below most estimates of the natural rate of unemployment,” adding that there was “no evidence that the economy’s currently overheating.”

If the Fed doesn’t lower it’s longer-run unemployment rate, it opens a question: how does the Fed move joblessness from 3.5 percent in 2020 to 4.5 percent in the longer-run? Restrictive policy is never especially popular, but a policy that intentionally leaves more than 1.2 million people jobless could be a heavy lift. (That’s the number you’d have to add to the jobless population to push today’s 3.8 percent unemployment to 4.5 percent, all else equal -- so it’s an unrealistic but illustrative back-of-the-envelope exercise.)

“You know when that happens normally? In recessions. That’s not what they’re forecasting,” said Seth Carpenter, chief U.S. economist at UBS Securities and a former Fed official. Instead, they’re looking to gradually lift rates enough to restrain the economy and hold back hiring. “That has to be the answer: they are restricting the growth rate.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Jeanna Smialek in New York at jsmialek1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Murray at brmurray@bloomberg.net, Alister Bull

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.