With Rates Below Fed's, Asian Markets Head for Rare Ground

With Rates Diving Below Fed's, Asian Markets Head to Rare Ground

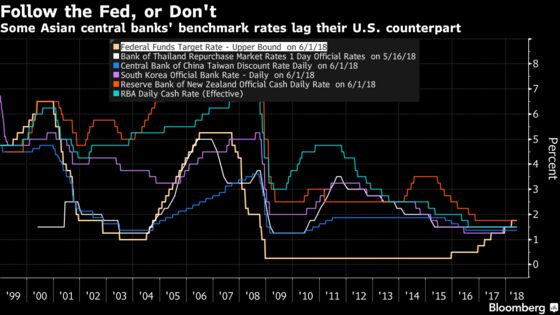

(Bloomberg) -- With faster growing economies typically generating quicker inflation rates, emerging Asian nations usually have benchmark interest rates above those in the U.S. That’s changing.

The Federal Reserve is all but certain to raise its key rate by a quarter point this week, meaning it will then have a benchmark above that of five counterparts in the Asia-Pacific region excluding Japan. The latest to join the group will be New Zealand, whose policy rate will fall below the Fed’s for the first time since 2000.

While Indonesia, India and the Philippines -- all with key rates much higher than the U.S. -- struggle to cope with the Fed’s tightening, investors remain comfortable with a negative differential in some cases. For Thailand and Taiwan, current account surpluses are a key buffer. For New Zealand, South Korea and Australia, real yields remain attractive.

Here’s a selection of views from economists and investors:

Chua Hak Bin, senior economist at Maybank Kim Eng Research Pte in Singapore:

- "Other countries’ benchmark rates can fall below the Fed funds rate so long as the currency prospects compensate for the interest differential." He cited the case of Thailand, where investors are willing to accept lower short-term rates relative to the U.S. because of the expected appreciation bias on the back of large current account surpluses.

- "Countries with large current-account deficits may face currency pressures if their policy rates are perceived to be overly low and accommodative relative to U.S. benchmark rates."

Robert Subbaraman, Singapore-based head of emerging markets economics at Nomura Holdings Inc.:

- "It is an interesting phenomenon" to be below the Fed’s benchmark, because the natural rate of interest theoretically should be linked to an economy’s growth potential and, for emerging markets, a risk premium for the chance of a boom-bust cycle.

- One reason for falling below is large current-account surpluses, which can reflect weak domestic demand. These economies "have faced currency appreciation which is tightening monetary conditions, and so no need to raise rates when inflation is low and domestic demand subdued."

- "Many of these countries have high domestic debt" that make them more sensitive to high interest rates, again explaining why their benchmarks might be kept lower.

- "A third reason is that many of these economies are quite open and/or exposed to commodity prices. Given the high uncertainty over the global economic and financial market outlook and given inflation is contained it may make sense to err on the side of laxity."

Ashley Perrott, head of pan-Asia fixed income at UBS Asset Management:

- "Thinking about where money and fund flows have gone since the global financial crisis, they’ve gone into high-yield opportunities," including emerging markets.

- Now that the U.S. is a higher-yielding market, those flows may head home, forcing borrowers to pay higher coupons or currencies to depreciate.

Mayank Mishra, global macro strategist at Standard Chartered Bank:

- "Rate differentials do matter, but they’re not the only thing that are driving currencies." Faster growth and muted inflation make currencies like South Korea’s won and Thailand’s baht likely to continue appreciating.

- Real interest rates have been rising steadily for developing markets even as they have dwindled in the U.S. and elsewhere.

Tamara Henderson, Bloomberg Economics:

- "For Thailand, Taiwan and South Korea, the negative interest rate differential with the U.S. is probably less of a factor in the central bank reaction function because these countries have large current account surpluses. This suggests less concern about attracting foreign bond investors."

- "For Australia and New Zealand, which have to worry about funding sometimes very sizeable current account deficits, the interest rate differential is more important. That said, at the moment both the RBA and RBNZ are probably ok with a bit less upward pressure on their currencies. I would not expect the interest rate differential to become a driving force for RBA/RBNZ rate decisions unless the currencies started to plunge."

Haibin Zhu, chief China economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co.:

- In the case of China, which maintains benchmark rates significantly above those in the U.S. but has on occasion followed the Fed in raising borrowing costs, it will be important to put domestic considerations first.

- "If you follow the Fed and hike too early, that will be dangerous" as China pursues a measured course of financial deleveraging.

--With assistance from Eric Lam.

To contact the reporters on this story: Enda Curran in Hong Kong at ecurran8@bloomberg.net;Gregor Stuart Hunter in Hong Kong at ghunter21@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Christopher Anstey at canstey@bloomberg.net;Malcolm Scott at mscott23@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.