Trump Balks Over Billions in Secret China Loans to Poor Nations

China’s secretive lending practices in developing nations are drawing increased objections from the U.S.

(Bloomberg) -- China has showered $10 billion on debt-laden Ecuador over the past six years for energy and infrastructure projects -- part of a global effort by Beijing to finance development in poor countries that are rich with natural resources.

Yet terms on billions of dollars in Chinese financing across Africa, Asia and Latin America remain mostly secret. In Ecuador, for example, not even the oil minister knows what strings are attached to his country’s loans.

China’s secrecy-shrouded, multibillion-dollar lending program for poor countries that are rich in natural resources is spurring a backlash from the U.S., the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. They want Beijing to reveal more about its loans, and they want recipients to be more transparent about their own financial condition, including debt levels.

The pressure on China for added transparency comes as the Trump administration is squaring off with Beijing over what the U.S. calls unfair trade practices. President Donald Trump has threatened to impose tariffs on as much as $150 billion in Chinese imports while also cracking down on the country’s investments in American businesses. The two sides called a truce on Saturday.

“If you ask China for its terms you will not find them,” David Malpass, the Treasury under secretary for international affairs, said in a speech earlier this year, referring to loans made to Venezuela that were denominated in barrels of oil.

The opaque lending “undercuts the incentives of recipient governments to improve their business environments, governance structures,” Malpass said, and the deals “often consist of long-term contracts for commodity exports at prices favorable for China, not the exporting country.”

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has raised U.S. concerns about the risk that countries will default on their Chinese loans at IMF meetings last month and during a G-20 conference in March. Mnuchin, the IMF and the World Bank have asked China to join the Paris Club, a group of creditors that specializes in loans to governments and requires both its members and their debtors to adhere to transparency standards.

China has resisted, in part over concerns that other members would have a say in bilateral debt restructuring negotiations that could affect Beijing’s interests. The foreign ministry on Monday said its economic cooperation with other countries “is always above board and has no strings attached,” adding that it follows the principles of “equality, openness, mutual respect, transparency and win-win outcomes.”

‘Irresponsible Remarks’

“We always abide by market laws and international rules. We always pay great attention to debt sustainability,” foreign ministry spokesman Lu Kang told reporters on Monday. “We hope relevant countries can view this in an objective way and invest their time and energy in making contributions to other countries’ development instead of making irresponsible remarks on other countries’ efforts.”

The IMF released a policy paper in March examining public debt levels in low-income developing countries, a document interpreted as a criticism of China’s lending practices though it scarcely mentioned the country. A May 8 statement from the fund highlighted “debt distress” in 15 African nations, but without naming China as the culprit.

The Trump administration is also targeting China’s relationship with the World Bank, where the country remains a recipient of development money. The U.S. argues that the world’s second-largest economy no longer needs assistance from donor nations and is urging the bank to review the arrangement and wean China off its programs more quickly.

The World Bank loaned China $2.47 billion last year, the most since 1998. In a deal this year with the Trump administration to increase its capital by $13 billion, the bank agreed to review its “graduation” policy, according to a bank official.

The U.S. campaign reflects concern in Washington that China’s expanding role in the developing world will undermine American influence, a fear that dates to the George W. Bush administration. The Trump administration’s National Defense Strategy released in January accused China of trying to gain “veto authority” over other nations’ economic decisions, and it has also specifically cited state-investment and loans as a way Beijing was pulling Latin America “into its orbit.”

The dispute over China’s development loans is just one front in that broader economic conflict with the U.S., the subject of talks in Washington between Chinese Vice Premier Liu He and top Trump administration officials in recent days.

China has vowed to retaliate for any tariffs by imposing its own duties against U.S. exports.

Foreign Spending

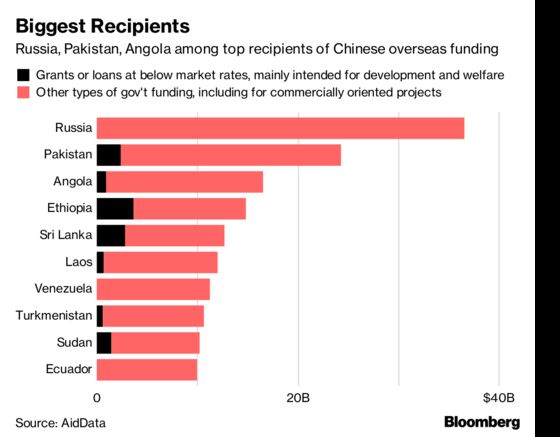

China’s foreign infrastructure spending has exploded, bolstered by its “Belt and Road” trade plan announced in 2013. China provided $354 billion in overseas financial support from 2000 to 2014, according to AidData, a research group at the College of William & Mary, rivaling the U.S.’s own $400 billion in development assistance during the period. Since 2010, the annual flow of money from China has exceeded funding from the U.S., according to the group.

But there is an important difference between the two countries’ aid. While 93 percent of U.S. financial support during the period came in the form of direct aid or loans made on concessionary terms, less than a quarter of Chinese assistance did, according to AidData.

“These loans are a problem,” said Edwin Truman, a researcher at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington and a former Treasury official. “If a country gets in trouble, or is in arrears, China or the recipient country may not alert the IMF. And then they find themselves seeking debt relief from the IMF.”

Russia has accepted more in Chinese development funding than any other country. Elsewhere, Chinese money is behind a four-lane highway in Sri Lanka, bridges in Angola, motorways in Pakistan and a railway company in Venezuela.

China often demands public-sector assets as collateral. It doesn’t always offer information on its loans’ structure, or when a debt is in arrears, according to an IMF official. Many recipient nations also don’t provide data on their debt and economic indicators. That means ratings agencies, international lending institutions and banks may miss red flags before a country needs a bailout, the official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

In Ecuador’s case, the debt-laden country -- with just a $98 billion economy -- was desperate for cash, having surpassed its legal borrowing limit of 40 percent of gross domestic product in 2016. Even though China’s loan to the country may eventually be repaid with oil exports, oil minister Carlos Perez doesn’t know the precise terms of the arrangement, demonstrating the opacity of the Chinese debt.

Ecuador released new data on Thursday showing that it owes China $7.3 billion, though the terms remain unclear.

‘Naming and Shaming’

“This is an area where there isn’t an overall authority and the best one can hope for is naming and shaming of the Chinese authorities until they become more transparent,” Truman said.

In Myanmar, China has agreed to build a $10 billion port in a remote town of 50,000 people on the Bay of Bengal.

The offer includes the participation of a Chinese state-owned investment corporation, which has proposed taking a 70 percent stake in the project. The Myanmar government and central bank are nevertheless worried that its $75 billion economy, one of the smallest in southeast Asia, will struggle to repay its share of the debt.

Chinese infrastructure loans could be a boon to the developing world, Malpass said. But, he added, that depends on whether “the terms are fair and projects are market-oriented.”

--With assistance from Jordan Yadoo, Andrew Mayeda, Stephan Kueffner, Peter Martin and Jason Koutsoukis.

To contact the reporter on this story: Saleha Mohsin in Washington at smohsin2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alex Wayne at awayne3@bloomberg.net, Mike Dorning

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.