Biggest Fear for World Growth Is Fear Itself as Markets Fret

Financial markets risk becoming the tail that wags the dog.

(Bloomberg) -- Financial markets risk becoming the tail that wags the dog.

While policy makers insist the global economy’s low-inflation expansion looks intact despite a first quarter slowdown, investors are presenting challenges. Rising bond yields, a jump in the price of oil beyond $70 a barrel, skittish stocks and cracks in credit could all end up undermining growth.

The worry is that unless markets start buying into the more optimistic outlook, their pessimism will become self-fulfilling by causing consumers and companies to lose confidence and slow spending. The Bank for International Settlements warned last year that the next recession will perhaps be triggered by a financial cycle bust, mirroring the events of 2001 and 2008.

The threat is all the more pressing given the value of financial assets keeps getting bigger. The ratio of assets to gross domestic product is now 10 times, compared to six times in early 1990s, according to Stephen Jen, the CEO at Eurizon SLJ Capital.

“Central banks intentionally fueled the asset prices in the current cycle, through financial repression, to stimulate the real economy,” said London-based Jen. “Given the inflated global asset prices including equities, bonds and real estate, it would not at all be surprising that a synchronized correction in the global financial markets triggers a global slowdown this time around.”

Less Rosy

Morgan Stanley strategist Andrew Sheets this week highlighted a disconnect between the firm’s expectation of an economic “cycle that is maturing, but not ending,” and the “decidedly less rosy” view of markets.

Sheets attributed the divergence to talk of synchronized global growth already being priced in, and an expectation among investors that they need to brace for the end of ultra-loose central bank policies which have helped to deliver above-average asset returns despite below-average growth. The credit market already troughed earlier this year and the next asset to top out will probably be stocks, he said.

“By the third quarter this year, that’s when we think the forward earnings for the S&P 500 stop going up,” Sheets told Bloomberg TV this week. “It will be difficult for the market to rally beyond that.”

While a recent Bank of America Merrill Lynch survey of fund managers showed the majority still favor risky assets, respondents demonstrated the lowest faith that the global economy will strengthen over the next 12 months since February 2016. Forty-one percent predicted a recession in 2019.

Investors should probably pay more attention to signs of stress in the financial markets than economic data. After all, the global recession of 2008 was preceded by six years of global expansion until the sub-prime crisis hit. The 2001 economic slump was triggered by the dotcom bubble burst and followed nearly 8 years of synchronized global growth.

What our economists say... |

| "A raft of countries have reported GDP figures for 1Q in recent weeks and the picture for advanced economies is clear -- growth hit the skids at the start of the year," writes Jamie Murray, chief European economist for Bloomberg Economics in London. "But rather than a sign that the global expansion is running out of steam, the slowdown seems to be explained by bad weather and local idiosyncrasies. A rebound in 2Q looks likely." |

Signs in the market are currently less positive than economic data. A BofA model, based on bond yields and the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index, suggests a 25 percent probability of a U.S. recession in the next ten months, up from 10 percent last year.

This week has also seen turbulence in markets in Argentina, Indonesia and Turkey. At least one economist is getting worried -- Harvard’s Carmen Reinhart, co-author with Kenneth Rogoff of “This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly,” said Wednesday that emerging markets are in worse shape now than during the global financial crisis in 2008.

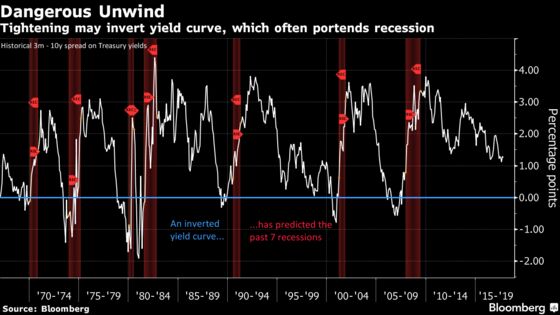

A lot of investor attention is also focused on the Treasury yield curve for providing a recession warning, a signal that becomes more powerful when it’s combined with widening credit spreads.

Fed policy makers must have watched these signs and wonder what it is the market is seeing that they don’t. San Francisco Fed President John Williams said this week he’s “very positive” about the economic outlook both in the U.S. and abroad.

Markets are often leading indicators of a broader downturn. Among all the 20 percent drops that have hit American stocks since the Great Depression, 10 preceded U.S. recessions. Only four recessions occurred without a bear market warning, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

More Moderate

Recent months have seen increasing evidence that the global upswing of 2017 is giving way to a more moderate period of growth. Markets have also been unnerved by political tensions such as scraps over trade and Brexit.

The slowdown has been most pronounced in Europe, with a report this week showing Germany, the euro area’s economic engine, saw its rate of expansion drop by half in the first quarter. Companies such as Continental AG and Volkswagen AG have pointed the finger at pressure from the stronger euro, which has risen 13 percent since the start of 2017, while rising oil prices are also increasing costs.

To be sure, most economists are betting on rebounding growth in the second quarter, attributing recent weakness to temporary factors such as poor weather, holidays and strikes in Europe. Even the effect of swings in some asset prices may be less pronounced. An analysis by Bloomberg Economics this week showed the global economic impact of oil hitting $100 a barrel won’t be as big as when that happened in 2011.

“Global growth will re-accelerate in the immediate months ahead,’’ Andrew Cates and Rob Subbaraman, economists at Nomura Holdings Inc., wrote in a May 15 report. “Indeed overall financial and monetary conditions remain supportive.’’

Still, the optimism of analysts may be cold comfort to some investors. A 2014 study by Prakash Loungani of the International Monetary Fund found that not one of 49 recessions suffered around the world in 2009 had been predicted by the consensus of economists a year earlier.

--With assistance from Brian Chappatta.

To contact the reporters on this story: Anchalee Worrachate in London at aworrachate@bloomberg.net;David Goodman in London at dgoodman28@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Paul Gordon at pgordon6@bloomberg.net, ;Paul Dobson at pdobson2@bloomberg.net, Brian Swint, Zoe Schneeweiss

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.